The Iran Delusion: How the U.S. Invented Its Favorite Enemy

Decades of U.S. coups, sanctions, and propaganda have shaped Iran into an enemy to serve Western geopolitical and economic interests.

For generations, Iran’s place in the American psyche has been shaped by a carefully curated mythology—one designed to obscure history, minimize inquiry, and justify domination.

Over the past seventy years, Iran has been cast in a rotating set of roles. According to U.S. history, it’s been an oil-rich partner, a Cold War chess piece, a revolutionary threat, a terrorist sponsor, and a nuclear menace.

None of these labels tell the full story. Together, though, they reveal something else: a pattern of narrative construction that frames resistance as radicalism and sovereignty as suspect.

Contrary to popular belief, the enduring conflict did not begin with religion or ideology.

It began when Mohammad Mosaddegh, Iran’s popular, democratically elected prime minister, pursued economic independence. This triggered a wave of foreign aggression that has reshaped the nation’s future.

In a word, it began with oil.

The Threat of a Free Iran

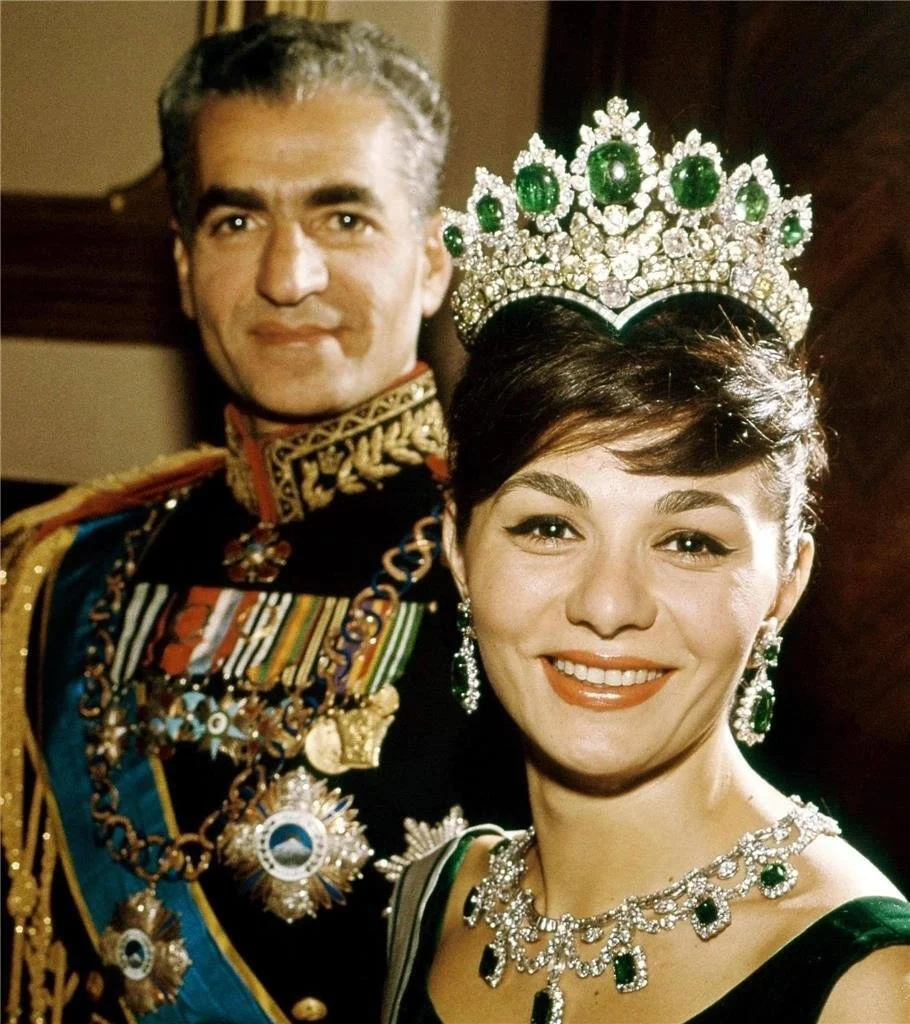

Before Mossadegh, Iran was ruled by Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi.

The Shah, an authoritarian monarch imposed upon the people by British imperial interests, was instrumental in preserving foreign control over Iran’s oil resources.

That changed in 1951, when Mossadegh secured a landslide vote of confidence from the 16th Majlis (parliament) and won the support and admiration of the people.

This support was demonstrated by massive street protests after the Shah tried to remove him from office.

Iran's Deputy Prime Minister is raised on the shoulders of supporters, as the crowd ralllies behind Mohammed Mossadegh.

Mossadegh’s popularity stemmed not from charisma or credentials, but from his resolve to confront foreign exploitation.

“The standard of living of the Iranian people has been very low,” he stated in a letter to President Eisenhower, “and it will be impossible to raise it without extensive programs of development and rehabilitation.”

For millions, his decision to nationalize the oil industry was a defiant stand against imperial exploitation—and a promise that Iran’s resources would finally serve its own people.

While widely popular inside Iran, nationalization was greeted with alarm by Western powers.

British officials, unwilling to concede their stake in Iranian oil profits, denounced the move. The U.S., fearing a ripple effect across the postcolonial world, began quietly weighing options to remove Mossadegh from power.

In the summer of 1953, Iran had a democratic government, an immensely popular prime minister in Mossadegh, and a bold plan to reclaim control of its oil.

Indeed, the nation was brimming with all the excitement and promise of a new era. That all came to an abrupt end.

As coups go, the overthrow of Iran’s government was remarkably swift. Orchestrated in secret by the CIA and Britain’s MI6, the planning spanned two months, while the actual coup unfolded in just four days.

The operation quickly gave way to decades of repression, foreign-backed rule, and enduring hostility between Iran and the West.

The Coup That Changed Everything

Mossadegh wasn’t a revolutionary. He was a Western-educated lawyer and a firm believer in constitutional rule.

When British officials refused Iran’s request to audit the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company’s books—citing concerns over questionable accounting and unequal profit-sharing—Mossadegh moved to nationalize it.

The decision was neither ideological nor hostile—it was economic. That fact didn’t matter to the West, and the imperialist machine went to work.

Like so many spaghetti noodles thrown at the wall, the U.S. exhausted a range of tactics to see what might stick—economic embargoes, frozen assets, propaganda campaigns, political extortion, and manufactured unrest.

Ultimately, when destabilization failed to unseat Mossadegh, they turned to a coup.

In Washington and London, officials branded Mossadegh a threat. They warned that his nationalist policies could inspire other nations to challenge Western oil concessions.

Behind closed doors, they painted him as veering toward communism, despite his vocal opposition to the Soviet Union. That framing became the pretext for intervention.

Western media framed Mossadegh as an agent of “chaos”

What followed was a textbook case of foreign-imposed regime change. During Operation Ajax, the CIA paid mobs to riot in the streets, inserted fake news into Iranian media, and bribed military officers to take control.

Afterward, American and British officials framed the coup as a grassroots revolt. In reality, Mossadegh remained immensely popular.

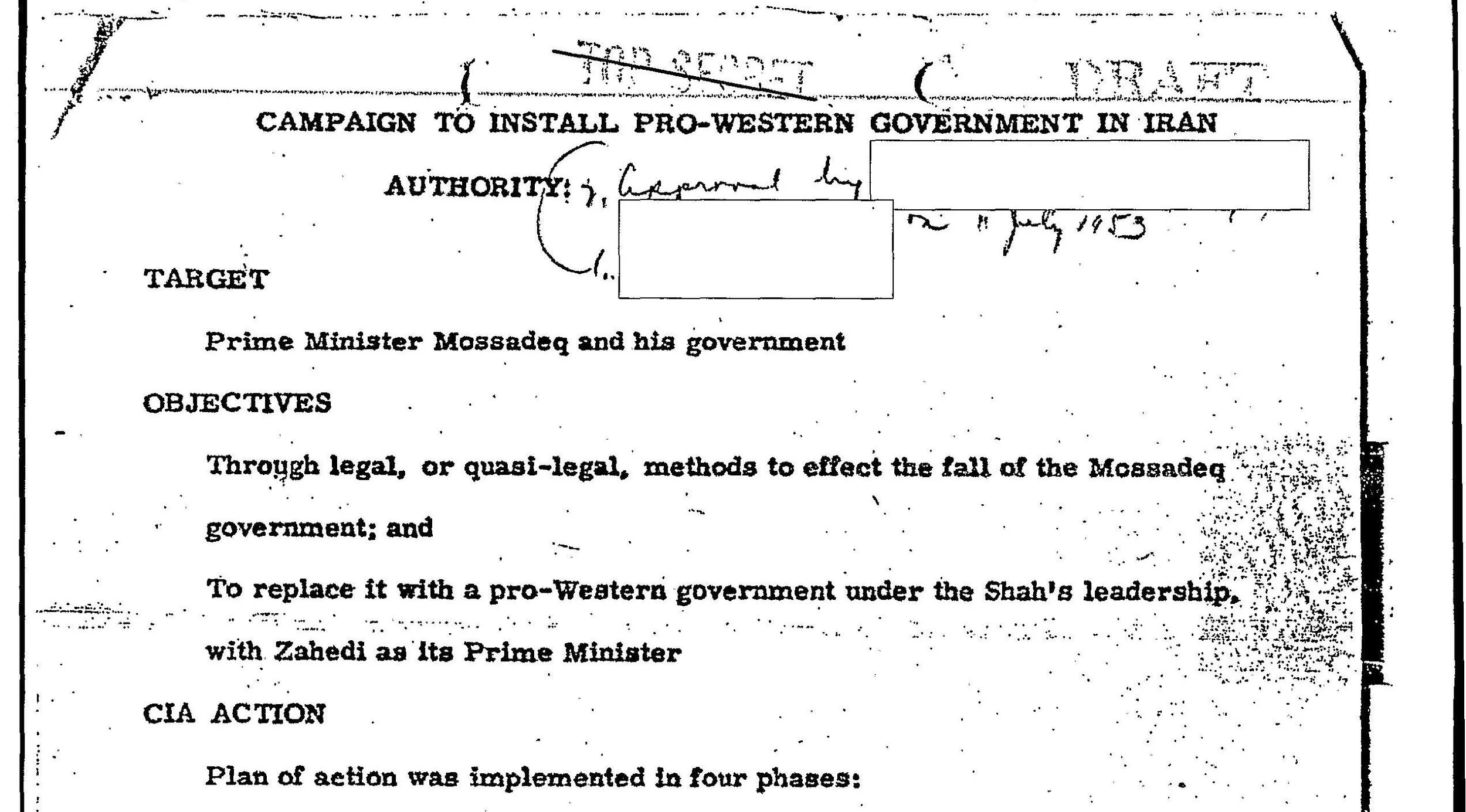

Read more: Declassified CIA document titled "Campaign to Install Pro-Western Government in Iran"

The fiction of a “popular uprising” masked the truth of a foreign-orchestrated power grab—one that would serve as a model for future coups throughout the Global South.

When it was over, the Shah returned from exile to rule as an absolute monarch. Western oil interests regained access to Iran’s reserves. Democracy did not.

Three years after the Iranian coup, Egypt’s President Nasser nationalized the Suez Canal, reclaiming a critical trade route from Western control.

In response, Britain, France, and Israel launched an invasion. This time, however, they were foiled.

Still, the message was clear: when postcolonial nations move to control their own resources, the West treats it as provocation.

The 1953 coup became a watershed moment for Iran. It showed that elected governments could, and would, be toppled in defense of foreign capital—and that the appearance of instability could be engineered to justify intervention.

It also left a scar that never fully healed. The memory of foreign meddling—and the brutality that followed—fueled the anger and suspicion that would later erupt during the 1979 revolution.

Fire blazes during the 1953 coup, backed by the CIA and MI6

What Washington called Cold War containment, Iranians experienced as betrayal.

The cost of that betrayal would be measured in decades of repression, economic hardship, and generations raised with the knowledge that their democracy had been dismantled to serve Western power.

How to Make an Enemy

For more than two decades after the coup, the United States stood firmly behind the Shah.

In their eyes, he represented a modernized Persia—a departure from what the West has long perceived as archaic, shaped by decades of orientalist projection.

In 1977, President Jimmy Carter praised Iran as “an island of stability,” unaware that the foundation beneath it was already beginning to crack.

To many inside the country, the Shah’s rule looked very different. His regime—sustained by oil wealth and fortified with American military and intelligence aid—had grown increasingly repressive.

Political dissent was crushed by SAVAK, the Shah’s feared secret police, whose methods of surveillance, coercion, and intimidation tactics were sharpened through U.S. and Israeli support.

Most harrowing among these tactics were the torture chambers, used to instill fear and crush dissent.

Public protest was outlawed. Political parties were dissolved or co-opted. The press was tightly controlled by the state.

While Western media spotlighted the Shah’s lavish parties and infrastructure projects, a growing number of Iranians were being imprisoned, silenced, or forced into exile.

Among the most prominent voices of dissent exiled during that time was a mid-ranking cleric named Ruhollah Khomeini, who had denounced the Shah’s capitulation to Western power and the 1963 “White Revolution.”

Banished first to Iraq and later to France, Khomeini’s message—delivered through smuggled sermons and cassette tapes—gained traction across social classes, gradually elevating him as the spiritual figurehead of Iran’s resistance.

By the late 1970s, the illusion of stability had collapsed. Mass protests swept across the country, uniting a wide swath of opposition—from secular leftists to religious leaders, students, workers, and everyday citizens.

Their shared demand was clear: the Shah had to go. Thus began the Islamic uprising—a popular revolution against decades of authoritarian rule backed by foreign power.

When the Shah fled Iran in January 1979, Ayatollah Khomeini became de facto leader of the revolution. By that point, Mossadegh—who was placed under lifetime house arrest by the Shah’s SAVAK—had died in confinement a decade prior.

Khomeini had spent years in exile uniting the various factions of resistance—religious leaders, leftists, nationalists, students—into a single movement capable of toppling the Shah.

Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini returns from exile, Tehran Airport, Feb 1, 1979

Ironically, the revolution that brought him back began as a broad and largely secular movement—uniting nationalists, leftists, students, and clerics in opposition to monarchy and foreign domination.

The anger that fueled it had deep roots. It was personal. Iranians remembered 1953. They remembered the torture chambers. They remembered who had propped up the Shah and kept him in power.

That memory boiled over on November 4, 1979, when a group of Iranian students stormed the U.S. Embassy in Tehran and took 52 American diplomats hostage.

For the students, the embassy was the nerve center of decades of covert interference and state repression.

The hostage crisis would last 444 days, and it would harden American opinion in a way few events ever had. The respective narratives were written.

In the U.S., Iran became synonymous with terrorism, while in Iran, the United States became the “Great Satan.”

Western media framed the embassy crisis as an inexplicable outburst of religious extremism, stripped of historical context. Words like “militant,” “fanatic,” and “terrorist” dominated headlines.

Almost no attention was paid to why so many Iranians saw the embassy not as a diplomatic mission—but as an outpost of empire.

True to form, the American public processed the event through a lens of superiority and exceptionalism—one that rarely accounts for the violence committed in the name of U.S. power.

Only after the seizure did the shape of post-revolutionary Iran begin to harden.

Once in power, Khomeini and his supporters moved quickly to consolidate control—sidelining secular voices, dismantling rival factions, and transforming a broad-based revolution into a theocratic regime.

A movement that had begun as a secular uprising was ultimately hijacked by religious authoritarianism—fulfilling the very narrative Washington had already imposed.

The crisis redrew diplomatic lines, hardened alliances, and recalibrated global strategy.

From that moment forward, Iran was no longer a wayward ally. It was a permanent adversary. The narrative of the Iranian “threat” had been locked in place.

Recommended viewing: The Secret C.I.A. Operation That Haunts U.S.-Iran Relations

Fueling the Fire

In 1980, war broke out between Iran and Iraq—a conflict that would drag on for eight years, claim hundreds of thousands of lives, and further isolate Iran on the world stage.

By that time, the United States had successfully cast Iran as a rogue state.

The revolution, the embassy seizure, and the collapse of a once-reliable ally had transformed Tehran from strategic partner to ideological adversary.

When Saddam Hussein launched a surprise invasion of Iran that September, Washington saw an opportunity—not to de-escalate, but to tilt the balance.

The Iran-Iraq War would become one of the bloodiest conflicts of the 20th century, lasting eight years and claiming hundreds of thousands of lives on both sides.

For the Reagan administration, the goal was not peace, but paralysis.

U.S. officials adopted a strategy known as “dual containment,” designed to ensure that neither country would emerge stronger than before. In practice, that meant quietly siding with Iraq.

Throughout the war, the U.S. secretly provided Saddam Hussein with intelligence, satellite imagery, and military aid, even as it became clear that Iraq was using chemical weapons against Iranian troops—and its own Kurdish population.

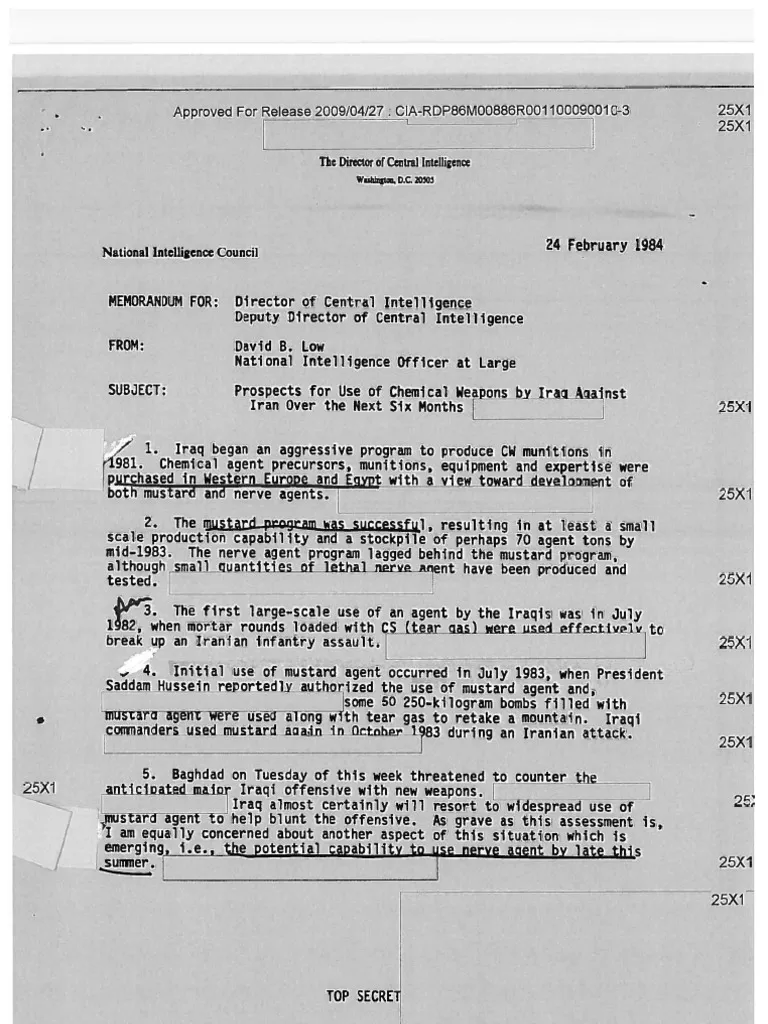

Declassified CIA intelligence memo from February 1984 confirms the U.S. was aware of Iraq’s use of mustard gas and nerve agents against Iranian troops.

Declassified documents confirm that American officials were fully aware of these violations of international law. They looked the other way.

However, in a stark example of the contradictory and covert nature of U.S. policy, the Reagan administration was simultaneously and secretly selling arms to Iran, in the hope of securing the release of American hostages held in Lebanon.

Publicly, Iran was branded a pariah. Privately, it was still a trading partner—proof that in Washington, moral outrage can always be shelved when geopolitical convenience requires it.

By 1983, Iraq’s use of mustard gas and other nerve agents had become routine on the battlefield. Yet that same year, President Reagan sent a special envoy—Donald Rumsfeld—to Baghdad to meet with Saddam.

The photo of their handshake would later come to symbolize the moral contradictions of U.S. foreign policy: condemning terrorism on the one hand, while arming and legitimizing a dictator on the other.

Iran, meanwhile, was left to fight alone. Cut off from Western arms and surrounded by enemies, it absorbed repeated chemical attacks with no meaningful response from the international community.

That sense of abandonment hardened the revolutionary state's posture and deepened its distrust of global institutions.

It fed the belief that survival depended on self-reliance, not diplomacy. Then came the revelation that confirmed those suspicions.

The handshake: Sadam Hussein and Donald Rumsfeld in Baghdad

Even as the U.S. publicly backed Iraq, it was secretly selling weapons to Iran in exchange for hostages and funneling the profits to right-wing Contra (counter-revolutionary) militias in Central America.

Iran-Contra confirmed what many in Iran already believed: that American strategy wasn’t guided by principle or consistency—it was driven by interests, and interests alone.

The war ended in a brutal stalemate in 1988. Iran had lost nearly 300,000 lives and gained no meaningful concessions.

Iraq, backed and armed by the West, lost between 150,000 and 250,000 troops, would, incidentally, become America’s next target.

For Iran, the war was a crucible. And for U.S. policymakers, it was another chapter in the effort to bleed the revolution dry—by any means necessary.

That campaign of attrition never fully ceased, however, in the chaotic aftermath of the Sept. 11 attacks, something shifted—briefly.

Axis of Evil

In the days following the World Trade Center attacks, Iran condemned the assault, and expressed sympathy for the American people.

They quietly helped the U.S. root out the Taliban in Afghanistan—a shared enemy that had long threatened Iran’s eastern border.

There were even backchannel meetings between Iranian and American diplomats, raising the possibility—however briefly—of a reset.

Then came the speech.

In his 2002 State of the Union address, President George W. Bush grouped Iran with Iraq and North Korea as part of an “Axis of Evil.” The phrase landed with force.

Overnight, the tentative progress made behind the scenes was obliterated. Tehran was blindsided. There had been no warning, no explanation—only the message that, once again, Iran had been marked for confrontation.

The label rewrote the post-9/11 script, casting Iran as a state that not only defied U.S. interests but potentially harbored ambitions as dangerous as those of Saddam Hussein.

Never mind the fact that Iran and al-Qaeda stem from opposing sects of Islam and historically despised one another—especially at the time of the 9/11 attacks.

There was no evidence of collaboration in the attacks themselves. Any later tactical tolerance has reflected strategic calculation, not shared ideology.

However, the West’s narrative served to justify a new foreign policy doctrine—one based on preemption, militarization, and unilateral action.

The invasion of Iraq the following year deepened Iran’s anxieties.

Saddam Hussein, once an enemy of Iran and an ally of the West, was toppled by American forces on the claim that he possessed weapons of mass destruction.

No such weapons were ever found, and the claim was debunked. Nevertheless, war ensued, reinforcing the message: false intelligence could, and would, still be weaponized to justify war.

Then came a familiar loop: Iran ramped up its defense posture and regional alliances, which the U.S. interpreted as aggression—thereby validating the “threat” narrative.

At every step, Iranian moves to deter invasion were portrayed as provocations.

Washington was either indifferent or ignorant of the fact that U.S. forces had now surrounded Iran on virtually every front.

U.S. Bases surrounding Iran. (Context: the U.S. has 800 bases in 70 countries)

Inside Iran, the backlash to the “Axis of Evil” speech was swift and political. Reformist factions who had supported engagement with the West quickly lost influence.

Those who warned that the U.S. could never be trusted gained ground. Any window for diplomacy that opened in the wake of 9/11 was abruptly shuttered.

Years later, many officials involved in Iran policy would admit that the speech had been a strategic error. By then, however, the damage had calcified.

The American public had absorbed the new narrative. Iran was no longer unknown to the mainstream—it was a villain in the post-9/11 world order, a country to be feared, sanctioned, and, if necessary, targeted.

The Nuclear Standoff

Of the myriad details missing in Western reporting on Iran one in particular has especially eluded American minds: Iran’s nuclear program began with U.S. support.

Under the Shah, the U.S. helped build the country’s first reactor and supplied weapons-grade fuel through Eisenhower’s Atoms for Peace initiative.

It wasn’t until after the 1979 revolution that the same program—now under the Islamic Republic—was recast as a global threat.

The United States promptly ended its participation with Iran. What had once been seen as a marker of modernity was now framed as a veiled attempt to build a bomb. Suspicion became policy.

Over the next two decades, Iran’s nuclear ambitions would become the central justification for a sweeping campaign of sanctions, sabotage, and military threats.

On Jul. 3, 1988, Iran Air Flight 655 was shot down by the USS Vincennes, which had entered Iranian waters. All 290 civilians on board—including 66 children were killed.

The event prompted George H. W. Bush to famously remark "I'll never apologize for the United States of America, ever. I don't care what the facts are."

In the West, the concern was framed as proliferation: the fear that a hostile regime might acquire nuclear weapons and destabilize the region.

In Iran, the concern was survival. Surrounded by nuclear-armed states—Pakistan, India, Israel, and the U.S. military itself—Iran viewed a nuclear capability as a deterrent, not a provocation.

Officials insisted the program was for civilian energy use, pointing to Iran’s rights under the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty. Washington wasn’t buying it.

In 2003, Iran’s Supreme Leader issued a binding religious edict—a fatwa—prohibiting the development, stockpiling, or use of nuclear weapons.

In 2003, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei issued a fatwa against the development of Iranian nuclear weapons

Yet even as Western headlines painted Iran as a rogue nuclear state, the U.S. intelligence community had already reached a different conclusion.

A 2007 National Intelligence Estimate, reflecting findings dating back to 2006, assessed with “high confidence” that Iran had truly halted its nuclear weapons program in 2003.

Nevertheless, critics have dismissed the fatwa as symbolic, despite it having been reaffirmed and cited by Iranian officials as a core principle.

That dismissal reveals a deeper contradiction: Western narratives depict Iran as a theocracy ruled by religious zealots, yet refuse to acknowledge the theological weight of one of Islam’s most sacred legal pronouncements.

The fatwa’s continued invocation complicates the portrayal of Iran as a rogue nuclear aspirant and underscores an internal tension between deterrence, doctrine, and a desire for national survival.

When Compliance Isn’t Enough

The standoff intensified throughout the 2000s, with Israeli officials repeatedly warning of an “imminent” Iranian bomb—an impending deadline that kept moving year after year.

Then, in 2015, after more than a decade of mounting tensions and failed negotiations, something rare happened: diplomacy prevailed.

Iran and six world powers signed the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA).

The deal was hailed by nonproliferation experts as a major achievement. Iran complied. Inspectors confirmed it.

As per the agreement, strict, verifiable limits were imposed on Iran’s nuclear program in exchange for phased sanctions relief.

That changed in 2018, when President Trump unilaterally withdrew the from the JCPOA, calling it a bad deal. This, despite his own intelligence agencies confirming Iran’s compliance.

Sanctions returned—harder than before—and with them came renewed isolation and economic hardship for Iran.

Efforts to revive the JCPOA in the years that followed repeatedly stalled. Negotiators came and went, but the distrust ran deep.

By late 2023, no agreement had been reached, and the restrictions that once governed Iran’s nuclear program had begun to expire.

The move—driven by domestic politics, lobbying pressure, and hostility toward anything tied to the Obama administration—reignited the crisis.

Sanctions were redoubled. Iran, now facing the collapse of its economy and the betrayal of a signed agreement, resumed uranium enrichment beyond the deal’s limits.

Hardliners in both countries claimed vindication. In Iran, moderates who had advocated diplomacy were sidelined. In the U.S., the narrative of Iranian duplicity returned to the forefront.

Talk of war crept back into headlines and dedicated segments on the evening news. For objective observers, it was a replay of old patterns: even when Iran plays by the rules, the rules are subject to change.

Lost amidst the noise was a glaring double standard.

Israel, which possesses a secret nuclear arsenal and has never signed the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT), faces no sanctions.

Saudi Arabia has publicly expressed interest in nuclear capabilities, yet continues to receive American support.

The issue, it seems, isn’t the bomb, but rather, who wields it.

In the years since Trump’s withdrawal, efforts to revive the deal have faltered.

What remains is a fragile diplomatic shell—emptied of trust, hollowed by politics, and stalled by years of failed attempts to find common ground.

The Propaganda Machine

By the time most Americans hear about Iran, the parameters of acceptable dialog have already been established, dictated by the ruling class.

The language is familiar—"mullahs," "terror sponsors," "rogue regime"—and the framing rarely changes.

Mainstream media outlets routinely rely on anonymous intelligence sources, often echoing government talking points with little scrutiny.

Op-eds warning of Iran’s “imminent threat” appear regularly in national papers, authored by experts linked to think tanks funded by defense contractors, oil interests, or foreign governments with a vested interest in isolating Iran.

Meanwhile, Iranian perspectives—especially those critical of both the Islamic Republic and Western pressure—are almost entirely absent from the conversation.

When Iranian officials speak, they are framed as propagandists: however, when Western officials speak, their narratives are treated as fact.

Take the coverage of Iran’s nuclear program: headlines often frame enrichment as proof of a looming weapon, even when international monitors confirm compliance with agreements.

When diplomacy breaks down, Iran is blamed for intransigence—rarely is the U.S. role in torpedoing progress examined with equal intensity, or at all for that matter.

Language plays a quiet but powerful role. Words like “regime” are reserved for adversaries, while allies are led by “governments.” Militias supported by Iran are “proxies”; those supported by the U.S. are “partners.”

These choices shape perception. They define legitimacy.

Subsequently, Americans are left with a version of Iran that fits a policy agenda rather than the facts on the ground.

The Human Cost

Despite justifying sanctions against these regimes, it’s the people who actually suffer. Decades of U.S.-led sanctions against Iran have done more than strain the economy—they’ve reshaped everyday life.

Sanctions are often presented in the West as a cleaner alternative to war. No boots on the ground, no airstrikes—just economic pressure.

In reality, they’ve made it harder to find medicine, more expensive to buy food, and nearly impossible for ordinary Iranians to imagine a future untouched by geopolitics.

Banks are cut off from global systems. Inflation has soared. Unemployment, particularly among the young, has deepened.

While Iran’s political figures often finds ways to navigate the restrictions imposed by sanctions, it’s the public that bears the weight.

Hospitals struggle to import specialized drugs. Children with rare diseases go without treatment. Cancer patients face months-long delays.

Inside an Iranian pharmacy, medicine and supplies are hard to come by under crushing sanctions

During the COVID-19 pandemic, U.S. sanctions limited Iran’s access to vaccines and critical supplies, even as the virus tore through the population.

Human rights groups warned that the sanctions were undermining basic health care. The warnings were ignored.

Supporters of sanctions argue that humanitarian goods are technically exempt.

However, in practice, the threat of secondary sanctions has led companies and banks around the world to over-comply—refusing to do business with Iran at all for fear of triggering U.S. penalties.

The result is a de facto blockade, one that affects everything from insulin to baby formula.

Washington insists that sanctions are a tool to pressure the regime. Yet they as history shows, they have yet to curb Iran’s regional activity or brought the regime change the West has long clamored for.

Instead, all it has done is fuel resentment, empower extremism, and convince many Iranians that diplomacy is a trap. Inside the country, the narrative is clear: the West isn’t punishing the government—it’s punishing the people.

Every time sanctions are tightened, it’s the grocery stores and pharmacies, not the government ministries, that feel the effects.

This is the hidden cost of confrontation— one rarely discussed in press briefings or televised coverage.

For Iranians, isolation has become a fact of life. For American officials, it remains a preferred tactic. Meanwhile, the human cost continues to mount—quietly, daily, and with little sign of relief.

Selective Outrage

When it comes to Iran, the rules are clear—until they’re not. The same governments that demand accountability from Tehran often look the other way when their allies commit worse.

Human rights matter, but not in Riyadh. Nuclear nonproliferation is sacred, unless the arsenal belongs to Tel Aviv.

Civilian casualties are a tragedy, except when inflicted by U.S. drones or Israeli bombs.

This double standard isn’t a bug of Western foreign policy. It’s a feature.

Take Saudi Arabia, where dissidents are jailed, women’s rights remain tightly controlled, and public executions are carried out in broad daylight.

The country waged a years-long war in Yemen that killed tens of thousands and triggered one of the world’s worst humanitarian crises. It bombed schools, hospitals, weddings.

Still, Saudi Arabia continues to receive U.S. weapons, intelligence, and diplomatic cover.

Iran, meanwhile, is sanctioned for proxy conflicts, punished for missile development, and vilified for political repression.

To be sure, these concerns are not without credence, but they are uniquely amplified. Simultaneously, the crimes of others in the region are muted. The same standards simply don’t apply to allies, to say the least.

The contrast is stark with Israel. For decades, it has occupied Palestinian land and bombarded Gaza, killing and displacing civilians in staggering numbers.

Human rights organizations have accused Israel of apartheid policies. The International Court of Justice has an open case against the ethno-nationalist state for genocide.

In Washington, however, the criticism is denied, if not outright silenced or labelled anti-semitic.

Israel remains the only nuclear-armed state in the Middle East. Despite never having signed the NPT, it faces no sanctions, no inspections, no UN resolutions with real teeth.

Instead, Iran—an NPT signatory—has its civilian program scrutinized; treated like a criminal enterprise.

Even the language of international law is unevenly applied. When Iran supports militant groups in Lebanon or Iraq, it’s labeled state-sponsored terrorism by the United States.

When the U.S. arms militias in Syria, or backs coups in Latin America, it’s called strategic interest. Legal norms bend, definitions blur, and outrage is calibrated based on alliance.

These contradictions erode any perceived moral authority and fuel cynicism.

In Iran and across the Global South, they reinforce the belief that the international system isn’t built on rules, but on power; that law is a tool used to punish adversaries, not restrain allies. That human rights are a cudgel, not a compass.

Diplomatic Offers Rejected

For all the talk of Iran’s intransigence, its history is clearly marked by attempts at diplomacy—most of them ignored, dismissed, or otherwise quietly undermined.

Beneath the rhetoric of resistance and revolution is a lesser-told story: one of proposals tabled, compromises offered, and doors shut before they could open.

In 2003, months after the U.S. invaded Iraq, Iran sent a detailed proposal through Swiss intermediaries offering to negotiate on every major point of tension: nuclear transparency, support for Hezbollah and Hamas, recognition of Israel, even cooperation against al-Qaeda.

The Bush administration didn’t respond. Officials later admitted they didn’t even seriously consider it.

The overture wasn’t isolated. Iranian diplomats have repeatedly floated regional peace initiatives, from calls for a Persian Gulf security framework to suggestions of joint anti-terror operations.

Even the much-vilified Islamic Republic has shown, at key moments, a willingness to de-escalate—so long as it isn’t forced to surrender its sovereignty in the process.

Yet in the West, these gestures are often framed not as diplomacy, but as manipulation. Offers are dismissed as stalling tactics. Peace plans are buried under headlines about missiles or protests.

However, when Iran demands even basic reciprocity—like condemnation of Israeli airstrikes, or guarantees against future betrayals—it’s labeled as obstruction.

The myth of Iranian irrationality trods along. The demonization continues, even as its diplomats are sitting across the table, pen in hand.

In June 2025, as Iranian negotiators prepared for nuclear talks with European ministers in Geneva, Israeli warplanes began bombarding Iranian targets—killing several senior officials just as diplomatic channels were opening.

Israel labeled the operation preemptive—a term it’s long used to spin unprovoked aggression as strategic necessity

Still, Tehran remained at the table.

Days later, while engaged in rare direct dialogue with U.S. envoys, American forces launched their own strikes, this time attempting to destroy nuclear facilities.

Iranian Deputy Foreign Minister Abbas Araghchi (right) and Ambassador Majid Takht-Ravanchi, in nuclear talks in Geneva

This time, Iran called the timing “egregious,” declaring further negotiations “meaningless.” It’s a point that’s hard to dispute.

Every failed negotiation, broken deal, and unprovoked aggression reinforces the argument that engagement is futile.

Critics point to the collapse of the JCPOA as further proof that America can’t be trusted.

Thus, the space for compromise shrinks.

That space, incidentally, won’t reopen on its own. It will require more than backchannels and soundbites. It will require a shift in posture—from both sides—but especially from the one that holds the sanctions, the drones, and the media megaphone.

Manufactured Crisis

Escalation with Iran rarely happens by accident. Most commonly, it follows a rhythm: an accusation, a provocation, a response, and then the justification for more pressure. It’s an infinite loop built on mistrust and powered by narrative.

In recent years, the language around Iran has grown more explicit. No longer confined to sanctions and warnings, U.S. officials—especially under the Trump administration—began openly entertaining the idea of regime change.

Former national security adviser John Bolton has frequently called for it. Lawmakers floated bills to fund opposition groups.

Conservative media embraced self-styled “Crown Prince” Reza Pahlavi, son of the deposed Shah, as some sort of waiting-in-the-wings wannabe monarch.

Then came the assassinated Iranian scientists; then the explosions rocking nuclear facilities; then the cyberattacks targeting infrastructure.

Each time Iran has responded—by enriching uranium, launching drones, or mobilizing proxies—the reaction has been swift and severe. The pattern fed itself: act, react, repeat.

Just beyond the view of the headlines, the human toll mounts. Everyday life grows harder, and the sense of siege deepens.

The mechanics of the cycle are clear: provoke a response, then use that response to justify escalation.

It’s a strategy that turns resistance into evidence of guilt—and keeps diplomacy forever out of reach.

The cycle doesn’t stop at containment. Instead, it stretches into questions of power: who should rule, and who gets to decide?

As President Trump publicly teases regime change, the exiled Reza Pahlavi is mentioned by some as a U.S.-endorsed alternative—even though he remains largely unsupported inside Iran.

Of course, the will of Iranians wasn’t a factor when the U.S. propped up Pahlavi’s father, the exiled monarch—and there’s no reason to believe it would matter in the event of another CIA-backed coup today.

The great irony is that the more the West tries to force Iran to collapse, the more its resolve is fortified. The longer this cycle continues, the harder it becomes to distinguish what’s reactive and what’s planned.

What gets lost in the repetition is the idea that this wasn’t inevitable; crisis can be manufactured as easily as peace can be negotiated.

That a different outcome has always been possible—if only the will to listen had matched the will to dominate.

Breaking the Narrative

For more than seven decades, the story of Iran in the American political imagination has been more about utility than about truth.

Iran’s been a monarchist ally, revolutionary enemy, and nuclear bogeyman—depending on what the moment required.

Throughout the long tumultuous historic record, the only real constants have been power, control, and the narrative dominance that holds it all together.

That narrative cannot be dismantled with diplomacy alone. It requires confronting the history that built it—openly, honestly, and without the need to dress imperial interests in the language of human rights.

It means acknowledging that Iran’s worst instincts were often sharpened by external pressure, not resolved by it—that the coup in 1953 wasn’t an isolated snag, but the origin point of a long unraveling; that sanctions hurt people more than power. That selective outrage isn’t policy—it’s theater.

Just as with the lie that launched the war in Vietnam, it set a precedent—one that normalized deception as strategy and made public consent a matter of manipulation, not truth.

Real accountability means admitting what’s been done in the name of oil, imperialist order, and global supremacy.

It means questioning the entire premise that one nation—especially one with its own long record of violence—should define the terms of order for the rest of the world.

It means realizing that what Western institutions call peace is really nothing more than the enforcement of obedience.

As for peace? Peace requires more than renegotiating a deal or reopening a channel.

It requires letting go of the idea that Iran’s sovereignty is a problem to be solved, least of all by Western entities who are directly responsible for the unrest in the region, and beyond.

When former president, Joe Biden, claimed that those in Palestine are “driven by an ancient desire to wipe out the Jewish people off the face of the earth,” he wasn’t speaking history—he was perpetuating a fiction.

Such rhetoric plays into a larger narrative that insists Arabs have always harbored a blood-deep hatred of Jews.

In reality, Arabs and Jews lived for centuries in relative peace across Ottoman Arabia—governing, trading, and coexisting without the specter of existential war.

The end of that coexistence didn’t stem from ancient hatred, but from a 20th-century movement, when Zionist European Jews, after nearly two millennia in Europe, began asserting a divine claim to land already inhabited by others—land that had been inhabited for … years.

Backed by colonial powers, themselves long accustomed to fusing religion and politics, Zionist forces carried out ethnic cleansing through displacement, terrorism and acts of genocide. All of this is done in the name of a “divine right” from an ancient god.

The rhetoric about ancient hatred is not only incendiary; it’s ahistorical. For centuries, Arabs and Jews lived largely in peace across Ottoman Arabia—governing, trading, and coexisting in the cradle of civilization—long before Western colonial powers carved artificial borders and weaponized religion for their own ends.

The Iran case is part of a much larger pattern: a narrative strategy that erases memory and justifies domination.

The more these myths go unchallenged, the more they calcify into policy. What happens next depends on whether we’ll continue to allow the narrative to be hijacked, or we’ll finally hold those who willfully mislead the masses accountable.

Certainly, there’s no guarantee that Iran will reform under less pressure. However, there is absolute certainty in what continued hostility produces: repression, entrenchment, war.

The cost of the current approach is measured not just in bombs or budgets, but in opportunity lost, in lives diminished, in futures denied.

A future free of Western interferemce will not erase the past—but it’s undeniably the only way to stop repeating it.