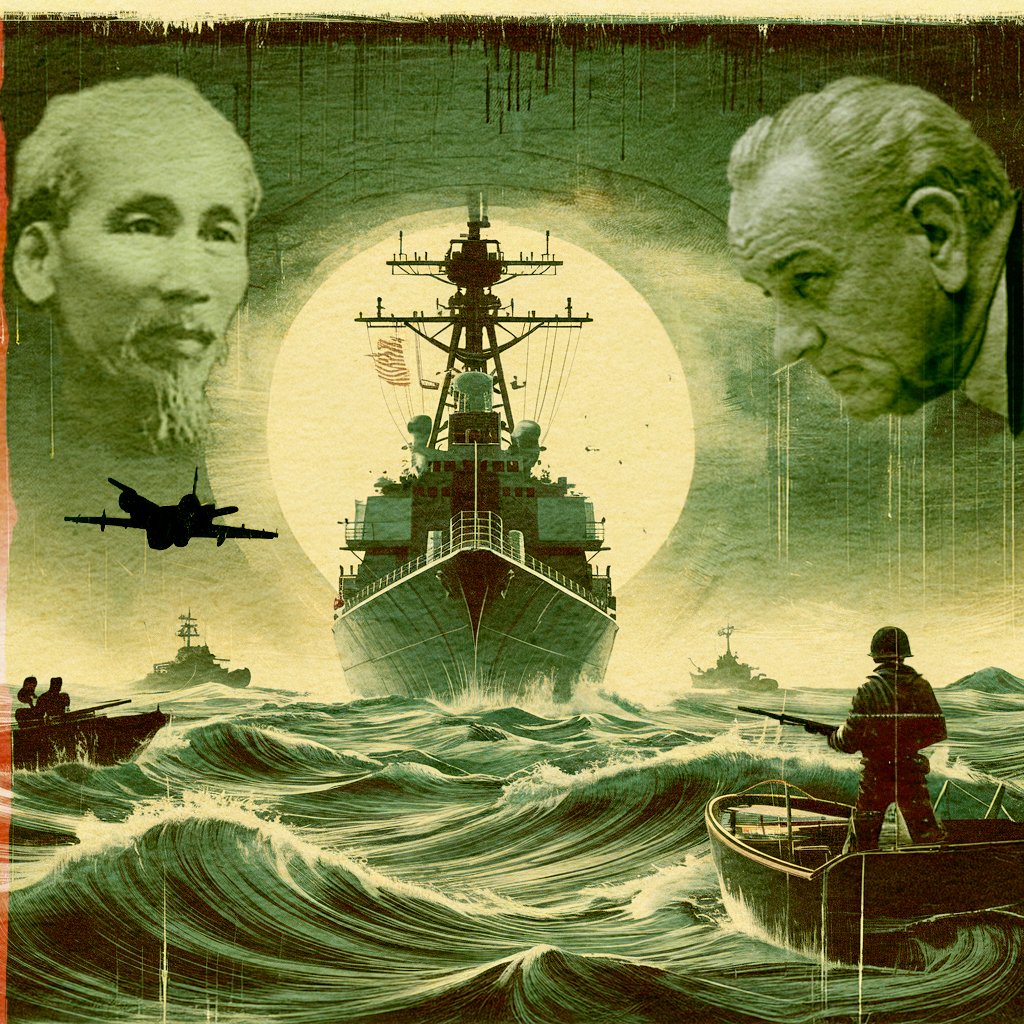

The Gulf of Tonkin Incident: The Lie That Led America Into Vietnam

The Gulf of Tonkin Incident was a fabricated pretext for U.S. escalation in Vietnam that shattered public trust and setting a dangerous precedent.

Of the practically innumerable lies perpetrated by the United States government, one of the more flagrant and consequential would have to be that which precipitated the Vietnam War.

With all due credit to the propaganda machine, framing the conflict as a fight against the scary, encroaching threat of communism was a masterstroke; an easily digestible narrative tailor-made for a well-conditioned American public.

That’s because when it comes to communism, the United States has a well-documented history of reacting with knee-jerk fear of anything remotely associated with the word, whether real or imagined.

Therefore, a conflict could, and would, easily be reasoned away in the minds of mainstream America, so long as the focus was hyper-fixated on a premise of fighting communism.

As the war dragged on, however, this narrative began to unravel, ultimately exposing the Gulf of Tonkin Incident as a manufactured excuse for escalation.

By the time the last helicopter left Saigon, 58,000 American troops and a staggering two million Vietnamese civilians would lose their lives.

Prelude to the Vietnam War

By 1954, Vietnam had finally thrown off nearly a century of colonial French rule, including a period of Japanese occupation during which Vichy France remained in administrative control.

That final struggle, known as the First Indochina War, culminated in France’s decisive defeat by the Viet Minh at Dien Bien Phu, followed by the Geneva Accords.

The accords temporarily divided the country at the 17th parallel and called for nationwide elections in 1956 to reunify Vietnam under a single, independent government.

However, those elections never happened, and the colonial structure didn’t collapse. Instead, it merely changed hands.

“The U.S. imperialists and the pro-American authorities in South Vietnam have been plotting … to prevent the holding of free general elections as provided for by the Geneva Agreements.”

Seizing on Cold War paranoia and the domino theory, the United States positioned itself as the new gatekeeper of Vietnam’s future—leveraging the Southeast Asia Treaty Organization’s (SEATO) legal and diplomatic cover to install anti-communist regimes and justify intervention.

Hồ Chí Minh, the Marxist-Lenninist revolutionary who had successfully led Vietnam’s resistance against both Japanese and French rule, had become the face of the country’s independence movement, much to the chagrin of the United States.

So the U.S. backed Ngô Đình Diệm, an authoritarian Catholic nationalist from the southern elite that had thrived under French rule—even as he resented the very Franco-colonial system from which he benefited.

Diệm aspired to fill the colonial void with a Western-backed, theocratic vision of Vietnamese nationalism.

Like so many governmental puppets, propped up by the United States, Diệm regime quickly became a tool of American interests.

The U.S. provided support in a number of ways, including in propaganda efforts. In coordination with the Southern regime, they dropped leaflets coercing civilians in the North to flee.

The regime ruled with repression and corruption, jailing political opponents, persecuting Buddhists, and implementing brutal “pacification” programs designed by advisors and funded in large part through USAID and CIA operations—many of them orchestrated by Diệm’s brother and chief political enforcer, Ngô Đình Nhu.

His government further served as a sanctuary for former Vietnamese colonial collaborators who simply rebranded their loyalty under a new foreign patron in the United States.

Select groups, like the Cao Đài and Hòa Hảo sects and the Binh Xuyên crime syndicate, were co-opted through U.S.-backed funding and political manipulation to stabilize the regime

Archival glimpse of U.S. officials in 1963 reckoning with their support for the Diem regime during martial law, Buddhist crackdowns

By 1963, cracks had surfaced in Washington’s support. Newly declassified tapes reveal that President Kennedy had grown favorable to the idea of removing Diệm, describing himself as “disposed to support” a coup amid intensifying religious and political repression.

That same year, the National Liberation Front, and its military arm, the Viet Cong, a southern revolutionary force aligned with the North’s call for reunification, gained momentum.

That shift set the stage for Cable 243, which green-lit Ambassador Lodge to push for regime change—culminating in the November 1963 coup and the assassination of the previously backed Diệm’.

By 1964, the United States was already engaged in covert warfare in Vietnam.

Under Operation Plan 34A (OPLAN 34A), it oversaw clandestine South Vietnamese commando raids targeting North Vietnamese coastal installations.

Simultaneously, DESOTO patrols involving the USS Maddox—a destroyer outfitted for signals intelligence (SIGINT)—conducted signals intelligence operations in contested waters just off the North Vietnamese coast.

*DESOTO was the name of the patroling program, referring to the first patrol ship, the USS DeHaven, hence the acronmym for DeHaven Special Operations off Tsingtao.

These so-called patrols were provocations by design—calculated moves intended to provoke a response while preserving a sort of plausible deniability.

Propaganda leaflets dropped by U.S. and South Vietnamese forces aimed to coerce Northerners and justify deeper anti-communist intervention.

A Phantom Attack, Phyisical Consequences

On August 2, 1964, the USS Maddox was operating in the Gulf of Tonkin as part of a DESOTO patrol.

Though publicly characterized as a routine surveillance mission in international waters, the Maddox was closely shadowing the coast of North Vietnam—monitoring radar installations, recording transmissions, and assessing military infrastructure.

At the same time, South Vietnamese commandos, directed and supported under OPLAN 34A, were carrying out covert raids against North Vietnamese coastal targets.

These commando assaults had taken place just hours before the Maddox’s encounter with three North Vietnamese P‑4 torpedo boats—small, fast-attack craft armed with torpedoes and machine guns.

Their interception of the Maddox was a logical response to mounting South Vietnamese attacks, coordinated and backed by the United States.

This context was deliberately withheld from the American in favor of the “unprovoked attack” narrative pushed by the Johnson administration.

During the skirmish, the Maddox fired warning shots before the Vietnamese boats returned fire with torpedoes, none of which struck their target.

The destroyer called for air support from a nearby aircraft carrier, and in the ensuing exchange, one Vietnamese boat was sunk, the others damaged.

The Maddox, by comparison, sustained only minor damage—one single bullet hole and no casualties.

U Boats visible from the USS Maddox August 2, 1964

It’s what happened next, however, that would plunge the U.S. into full-scale war.

On August 4, two days after the first incident, the Maddox was joined by the USS Turner Joy for continued operations. That night, amid a storm and poor visibility, both ships reported multiple sonar and radar contacts that they interpreted as a renewed torpedo attack.

The Turner Joy launched evasive maneuvers. Torpedoes were fired. Guns blazed.

The Navy would later log 21 hours of sustained alerts and hostile response fire. There was no enemy.

Captain John Herrick, commanding the task force from the Maddox, quickly grew skeptical.

In a series of urgent messages to the Pentagon, he expressed doubts about the validity of the radar readings, noting that the supposed attackers left no visual confirmation, no wakes, and no recovered debris.

That same morning, Defense Secretary Robert McNamara briefed President Johnson that aircraft from the USS Ticonderoga had sighted “two unidentified surface vessels and three aircraft” near the destroyers.

Admiral James Stockdale—one of the pilots overhead—would later counter that claim entirely: “There was nothing there but black water and American firepower.”

Captain John Herrick, commanding the task force from the Maddox, quickly grew skeptical.

In a series of urgent messages to the Pentagon, he expressed doubts about the validity of the radar readings, noting the supposed attackers left no visual confirmation, no wakes, and no recovered debris.

“Review of action makes many reported contacts and torpedoes fired appear doubtful,” he wrote. “Freak weather effects on radar and overeager sonar men may have accounted for many reports.”

Even Defense Secretary Robert McNamara was warned of the uncertainty. Internal NSA reviews later concluded that the second attack “almost certainly did not occur.”

In 2005, declassified intelligence confirmed that U.S. intercept operators had overheard North Vietnamese commanders explicitly stating they had not engaged any American ships that night.

Despite this, the Johnson administration did not hesitate to present the event as another unprovoked act of aggression.

In a televised address, the president claimed, “Repeated acts of violence against the armed forces of the United States must be met not only with alert defense but with positive reply.”

Intelligence, Deception, and the Machinery of Consent

While Johnson projected calm resolve in front of the cameras, behind the scenes, Defense Secretary Robert McNamara was already orchestrating the narrative. He helped strip the intelligence of its ambiguities and tailored the story to fit a predetermined course of action.

Captain John Herrick’s doubts about the second attack—flagged in real time—were quietly scrubbed from the version of events that reached the president and Congress.

The Gulf of Tonkin resolution, passed August 7, 1964

On August 7, Congress passed the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution, granting Johnson expansive war powers without a formal declaration of war. In the House, the vote was unanimous—416 to 0.

In the Senate, only two voices dared to dissent: Senators Wayne Morse of Oregon and Ernest Gruening of Alaska.

Gruening warned that the resolution would entangle the U.S. in a “hopelessly confused” war without end. He was right.

The resolution handed Johnson sweeping war powers without a formal declaration of war. What followed was immediate and unrelenting: airstrikes, troop deployments, and the steady transformation of Vietnam into a quagmire of American intervention.

By 1968, more than 500,000 American troops were stationed in Vietnam. The war machine fully activated not in response to crisis, but fueled by fiction.

Only years later did the full extent of that fiction come to light. In 1995, during a visit to Vietnam, Robert McNamara met with General Võ Nguyên Giáp, who told him bluntly that “absolutely nothing” happened on the night of August 4. McNamara did not disagree.

In the 2003 documentary The Fog of War, McNamara would go further, admitting that the so-called second attack never occurred. No misreading of sonar, no misunderstanding; it was just a flat-out, good old-fashioned lie.

Manufacturing Consent: Media, Messaging, and the Illusion of Unity

Long before McNamara’s belated admissions, the press in 1964 had done its part for the war effort. Far from questioning the official narrative, mainstream outlets served as an echo chamber for the administration’s claims.

Mainstream outlets parroted the story of unprovoked attacks on “routine patrols” in international waters.

The covert provocations and geopolitical calculations were buried beneath patriotic framing, and the public—blinded by Cold War dogma—rallied behind the president.

Then-former Vice President Richard Nixon (Eisenhower) used his considerable platform to stoke those sentiments further. In a 1965 Reader’s Digest article titled “Needed in Vietnam: The Will to Win,” Nixon lambasted the Johnson administration for its “compromise, weakness, and inconsistency.”

He called on the U.S. to expand military operations to North Vietnam and Laos, and insisted the country should use its military power “to win this crucial war—and win it decisively.”

He later urged the U.S. to “take a tougher line toward Communism in Asia,” framing any hesitation as a strategic liability.

His rhetoric fed directly into the public appetite for escalation, reinforcing a narrative that strength meant expansion, and diplomacy meant defeat.

The frequency of such deceptions was simply too consistent to be an anomaly; it was structural.

The media had already internalized the myth of American innocence and moral authority, making it the ideal conduit for war propaganda.

Inside the Pentagon, however, people knew better.

Daniel Ellsberg, who would later leak the Pentagon Papers, wrote that by the night of August 4—or within a day or two—it was already clear to those with access to classified information that the second attack never happened.

The public, however, wouldn’t learn the truth for nearly a decade.

L-R: Secretary of State Dean Rusk, National Security Adviser McGeorge Bundy, President Lyndon B. Johnson, Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara, and CIA Director Richard Helms.

A Template for Deception

The Gulf of Tonkin Incident, and the deceit that ensued, didn’t just mark a turning point in Vietnam—it became policy. The fabrication of crisis, the manipulation of intelligence, and the mobilization of public opinion through media complicity would repeat with chilling consistency in the years to follow.

In Grenada in 1983, just a few years before Iran-Contra, the U.S. launched an invasion under the pretense of rescuing American medical students, even as internal military assessments concluded there was no real threat to their safety.

The operation, dubbed Urgent Fury, was hardly about rescue, but instead an attempt to restore a pro-American government—sold to the public through carefully managed press blackouts and patriotic headlines.

In Panama in 1989, the U.S. invaded under the banner of defending democracy and bringing General Manuel Noriega to justice. Operation Just Cause, however, had deeper motives: asserting control over the Panama Canal and reestablishing military dominance in the region. Noriega, once on the CIA payroll, was only recast as a threat once he fell out of Washington’s favor.

In Iraq in 2003, the invasion was justified with a similarly manufactured tale of weapons of mass destruction and phantom ties to al-Qaeda—claims pushed through media channels that, once again, failed to question the official line.

The clearest and most catastrophic echo, though, is unfolding in real time. Following Israel’s June 13, 2025, airstrikes on Iranian nuclear, and the subsequent U.S. bombing of the same targets, Washington has dusted off its war chest of Cold War language and Iraq-era talking points.

Once again, Americans are hearing about “imminent threats,” “terror sponsorship,” and the “Axis of Evil.” Once again, the press repeats these claims with minimal scrutiny, and once again, a dangerous escalation is being packaged as inevitable, even righteous.

Each time the cycle repeats, the choreography tightens. The language may have evolved, but the strategy hasn’t—and this time, the stakes have climbed to a nuclear tier.

The narrative comes first. Evidence, or the illusion of it, is molded to match the mission.

Every institution involved—from intelligence agencies to newsrooms to Congress—followed the script to the letter.

The Perpetual Fear of a Phantom Enemy

Like family heirlooms passed down through generations, anti-communism sentiment in American political culture has never demanded much inspection—only dogmatic repetition.

This knee-jerk hostility isn’t typically born of any kind of grasp on the concept of communism or any of its tenets. It’s inherited, absorbed from predecessors who are just as uninformed; mystified by a scary word.

Politicians, pundits, and policymakers parrot the same Cold War soundbites with all the fervor of true believers, never pausing to ask whether the enemy they’re fighting even exists.

It doesn’t matter that a majority of Americans couldn’t define communism beyond long-regurgitated Cold War-era soundbites.

It matters less that many of the U.S.’ own social programs are rooted in communistic frameworks.

In America, ideology isn’t about comprehension. It’s about how something feels. Ignorance, proudly worn, is as American as apple pie.

Why the Lie Still Works

The Gulf of Tonkin Incident was a grift—plain and simple. It revealed how easy it is to sell a war to a country desperate to believe in its own righteousness.

More than that, it demonstrated just how little accountability exists for those who work in the service of crafting, selling, and maintaining the lie.

The lie, most certainly, is the product—tested, packaged, and ultimately bought by every American eager to be seen as a “patriot.”

From the NSA’s doctored intelligence to the media’s uncritical amplification, Tonkin revealed a repeatable formula: institutional coordination cloaked in credibility.

It became standard operating procedure for manufacturing consent.

The same pattern would resurface in Iraq, in Afghanistan, and in every so-called humanitarian intervention masking resource grabs or geopolitical chess moves beneath the language of “freedom” and “democracy.”

To be sure, Tonkin wasn’t an outlier—it was proof of concept.

Even when the truth came out—through Ellsberg’s leaks, declassified NSA reports, and McNamara’s own admissions—there was no reckoning. No indictments. No resignations. No reforms.

The War Powers Act of 1973, passed in the aftermath, was a performative gesture at best.

Presidents have sidestepped it with ease, leaning on euphemisms like “police actions,” “authorized use of force,” and targeted drone strikes to bypass Congress and evade public scrutiny.

Just as in decades prior, Trump’s recent airstrikes on Iranian nuclear sites—hitting facilities in Fordow, Natanz, and Esfahan—were launched without congressional approval and framed with the familiar pretext of an “imminent threat.”

Whatever comes next will presumably echo similar operations that precede it: escalation without oversight, violence without accountability.

The real legacy of Tonkin is its normalization of evading democratic oversight and public transparency.

False flags, controlled leaks, scripted briefings—each iteration is tailored to the moment, but drawn from the same playbook.

The formula persists because it delivers.

It still works—arguably better than ever—on a public trained to mistake propaganda for principle.

It works because modern journalism more often serves as an echo rather than an inquiry.

It endures because power answers only to itself—until it’s made to answer to someone or something else.

Its memory carries weight only if it disrupts the pattern—if it sharpens our ability to spot the lie before it becomes the next pretext for war.

The lie still works, but it only works only as long as we allow it to go unchallenged.