Politics of Deflection: Tone Policing in Service of Supremacy

Like a velvet glove over an iron fist, or a dagger bubble-wrapped in decorum, tone policing is the polished language of domination, concealing the violence of systemic power; not with a gag, but with a glower.

Amidst the unrelenting din of performative political discourse, there exists a quiet tyrant. Instead of power that barks orders or implements legislation, it wields shame, discomfort and condescension as weapons of suppression.

It doesn’t aim to silence the conversation outright; it works insidiously, creating the terms under which speech is allowed to exist. Such is the essence of tone policing, and the power-coded discourse regulation under which it functions.

As Michel Foucault observed, discourse, although perceived by most as a mere vehicle for communication, is a system of control. In every society, he noted, the production of discourse is managed through institutional procedures that determine who may speak, what may be said and how it must be said in order to be considered legitimate.

Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA) has expanded on this Foucauldian premise, exploring precisely how language reinforces existing power hierarchies.

It maintains that discourse functions not just as expression, but as structure—embedding power within the terms and expectations that govern communication. Within this structure, the tones, registers, and emotional modes preferred by those in authority become the only acceptable forms of public speech.

Tone policing is the mechanism through which this structure is sustained. It redirects dissent by focusing less on what’s being said and more on the emotion used to say it. Immediacy becomes volatility; resistance becomes verbalized defectiveness.

In this way, dominant groups control who speaks, as well as the conditions under which speech is declared valid. Elements like diction, delivery, and emotional restraint become the price of admission to ingroup spaces.

The result is a form of rhetorical gatekeeping through which marginalized groups are held to expressive standards constructed by, and for, dominant voices.

Voice as Privilege

This dynamic aligns with a foundational concept of discourse: that of the muted group. It holds that language systems—and the social norms governing their use—are not equally accessible to all, and often fail to reflect the realities or communicative needs of those outside the dominant culture.

Meanwhile, those in power operate on a different frequency altogether. They rely on a shorthand to which outgroups aren’t privy—a fluency coded in access, aesthetics, and deference.

Like George Carlin put it: “You don’t need a formal conspiracy when interests converge.” Regardless of how they came to be in the club, they all speak the same language: money. And money talks.

Within these constraints, the marginalized are expected to navigate spaces never meant to accommodate them. When their communication deviates—from the controlled and composed to something raw or resolute—it isn’t just dismissed; it’s pathologized.

Tone policing thrives in this environment. It tells the aggrieved and grieving to quiet their grief, the outraged to inhibit their indignation, the oppressed to package their pain for polite company—so as not to disrupt the emotional uniformity demanded by soft authoritarianism.

Often, this manifests through the use of thought-terminating clichés—succinct phrases that serve to end discussion and suppress dissent. Expressions like "it is what it is," "let's agree to disagree," or "everything happens for a reason" function not to engage with the substance of a grievance but to dismiss it outright, reinforcing existing power dynamics by prioritizing the comfort of the dominant group over the voices of the marginalized.

In this sense, it works as a sort of therapeutic discipline, mimicking the logic of disciplinary power in clinical settings, where emotions are filtered, re-coded, and managed to preserve order.

It demands composure in moments demanding disruption, lest emotional “deviation” be seen as a failure of mental wellness or acuity rather than a rational response to harm.

This discipline becomes laborious in an emotional sense. As Arlie Hochschild describes it, this emotional labor requires the speaker to control what they say, as well as how they should feel while saying it.

The toll is psychological, Hochschild determines. Emotional labor pulls people away from their own feelings—a condition he calls “emotive dissonance.”

When one is compelled to perform calmness in the face of institutional harm, what follows is not expression but impersonation. The internal discord this creates is profound—and corrosive.

Anyone who's worked a register or waited tables knows this script by heart: smile through the abuse, suppress the urge to push back, and swallow whatever righteous anger bubbles up behind your eyes. It’s not enough to do the job—you have to make it palatable. Perform niceness or risk punishment.

This is where that therapeutic discipline shows its teeth—not by silencing speech, but by shaping its emotional grammar. The individual is “free”—from exclusion, dispossession, starvation, etc.—so long as they submit their expression to the preferred aesthetics of power.

What begins as tonal containment metastasizes, ultimately, into historical erasure. Resistance, refined, softened, and rebranded, becomes ready for market.

Tone policing governs this process in real time. It manages emotional expression as the record is being written—preparing faux resistance not for liberation, but for branding.

From Silencing to Sanitization

Of course, discourse regulation isn’t only about controlling how dissent sounds in the moment. Tone policing sets the emotional terms of engagement, but it doesn’t act alone. It finds a counterpart in co-optation.

Implemented together, they shape how dissent is received, and, just as importantly, how it will be remembered. This makes it possible for the messaging of a movement to be hijacked or later be claimed by the very systems that once found it intolerable.

Co-optation functions by taking language rooted in legitimate critique and repositioning it as commentary, branding it for institutional PR.

In linguistic terms, it shifts content from Sentence Grammar (syntax, punctuation, etc.) into Thetical Grammar (conceptual styles of communication). It removes protest from the core message and tucks it away like a footnote, effectively hidden in plain sight.

Once the emotional edge of a movement has been sufficiently dulled, its language becomes easier to absorb. Slogans, symbols and even radical demands are re-anchored—divorced from their original intensity and repackaged within parameters that serve institutional goals.

Rather than amplify the message, they anesthetize it, bastardize it into a toothless rendering deemed presentable. It’s a decidedly "baby gloves" approach, amounting to a KIDZ BOP version of the actual issue.

Thus, thetical statements such as “we support equity” or “we hear you; we see you” function not as commitments, but as a means of stance-marking. They create an ambient sense of alignment while sidestepping action.

In this manner, co-optation emulates the air of dissent, rewriting its meaning through strategic placement and contextual anchoring.

It’s a quiet yet subversive arrangement; tone policing restrains the voice in the moment, co-optation rewrites the record. Together, they hammer resistance into submission—treating demands as secondary by re-centering how and where they are allowed to appear.

Norms That Restrict Expression

Tone policing enforces conformity through speech codes—unspoken rules regarding who can speak, how they should sound and what emotions are permissible in public expression.

These patterned constraints underpin every interaction. Whenever an injustice is named—racism, gendered violence, colonization—the response is more often redirection than engagement.

This enforcement becomes ritualized—disguised as feedback, delivered backhandedly as advice:

“This would be more effective if you weren’t so angry.”

“You’d be more convincing if you weren’t so emotional.”

“People would listen if you weren’t so divisive.”

These critiques carry no substance; they exist solely to trivialize the matter at hand by scrutinizing tone and timbre while downplaying the weight of dissent. Such criticisms demand politeness rather than substance, prioritizing manner over message.

The Performance of Politeness

Politeness, in this context, is not about mutual respect or common courtesy. It describes the delicate dance of managing impressions, adjusting language and calibrating emotion to conform to the preferences of the powerful—a core mechanism of tone policing.

While one might argue that tone regulation ensures productive dialogue—that it keeps conversations from devolving into chaos or aggression—this premise assumes a level playing field.

In practice, civility is rarely demanded of those in power. It’s foisted upon the marginalized as a precondition for being heard. In addition to managing how they speak, members of the outgroup must absorb the emotional projections of those in authority.

Tone policing ensures the message is judged by taste, not truth. The cost of this confinement is steep. The energy spent constantly repackaging lived experience (the constant code-switching and self-monitoring) is not merely rhetorical. It’s emotional erosion.

Framing theory explains the effectiveness of this tactic. The way a message is structured—its voice, packaging, and context—shapes how it’s received, or whether it’s received at all.

At the whim of the ingroup, a movement can be cast as disruptive rather than necessary; its standard-bearers, as irrational rather than impassioned. What gets promoted becomes legitimate, and the rest, ignored as irrelevant, negligible.

This isn’t a new trick, and it’s deployed with indifference to social norms—even those presumably anointed in sanctity.

Take the Bible—not as a compendium of scripture, but as discourse—for example. Across millennia, kings, popes, and institutions have revised, omitted, and selectively retranslated verses, chapters and even entire books to reflect a wide spectrum of personal, political and theological agendas.

What once read as a text of radical communalism and liberation has been repackaged as a mandate for righteous authority. In this bizarro rendering, liberation becomes obedience, and Jesus appears less like the man who overturned the tables than the merchants who sat behind them—more aligned with capital than with the poor and dispossessed he nursed and nourished.

The same principle underpins more modern mechanisms of control. Over time, this phenomenon begets a habitual practice for the marginalized individual: a self-policing loop.

Soon, churches begin compulsively reiterating a revised gospel. Under this doctrine, the rich are “blessed by God,” while poverty is framed as moral failure—not as the outcome of institutional forces so visible they’ve become almost tangible.

Congregants then go forth, wielding this borrowed moral superiority like a sword—demanding obedience from those over whom they themselves hold power.

The pattern continues. Expression narrows. Authenticity is traded for performance. Dissent is trimmed into shape—not to make it clearer, but to make it quieter.

Meanwhile, institutional power maintains a veneer of objectivity by feigning impartiality. It doesn’t erase dissent—it rewrites the rules of engagement, disqualifying truth on stylistic grounds while pretending to keep the floor open.

Tone and the Untranslatable

What often gets lost in this performance is a kind of expressive legitimacy, the freedom to speak in a way that reflects one’s emotional, cultural and experiential truth, not just sanitized logic or academic confines.

It’s the right to be heard without translation by a representative of the ingroup; the right to express anger without being labeled hostile, to mourn without being cast as unstable, to name harm in a voice shaped by the life it came from.

Tone policing erodes that validation by enforcing hegemonic discourse norms. These norms reward assimilation, detachment and decorum—values born of entitlement, and enforced through soft rituals of conformity that mirror the behavioral demands of a fascist order.

When gatekeepers impose dominant norms on marginalized groups, it’s an attempt to render them ineligible within the sanctioned bounds of public discourse. The correction is always cultural, the discomfort, always asymmetrical.

Beyond mere exhaustion, emotional labor resurfaces here as tactical depletion—a war of attrition waged through expectation. Every ounce of energy spent filtering one’s tone to appease is energy diverted from the strength of the message. Every rhetorical self-check becomes an act of defiance deferred.

It’s not just abstract theory—it’s a real space in which discomfort gets written out of the official narrative.

Interestingly, the more resistance is softened or silenced now, the easier it becomes for others to claim they never opposed it. As Omar El Akkad has articulated, “One day, everyone will have always been against this.”

Systems of harm don’t always need to silence dissent. If they can extract just enough angst, if they can just capture enough revolutionary spirit, they can dissolve any movement into utter meaninglessness.

Speech isn’t merely shared. It’s controlled, repressed, and when possible, repackaged for public consumption.

Ultimately, what can’t be muted is reshaped: it’s stripped of urgency, rebranded as more palatable content, and redistributed as a softened fragment of its original force.

How Media Manufactures Palatability

This practice plays out clearly in news coverage, where broken windows cut into regularly scheduled programming, but broken bodies and broken lives fade to the margins.

Property damage gets amplified, while the conditions that created it scroll beneath the lower chyron—reduced to afterthoughts, if they appear at all.

This isn't just editorial bias or journalistic malpractice (though it is both)—it also exemplifies the concept of agenda-setting. This concept holds that while media messages might not dictate what we think, they very much dictate what we think about.

During the 2020 Black Lives Matter protests, for instance, property damage received disproportionate coverage compared to police violence that sparked demonstrations. According to data from the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED), more than 93% of racial justice protests were entirely peaceful, yet confrontational incidents dominated media coverage and shaped public perception.

Meanwhile, coverage of police brutality was largely confined to expert analysts and mainstream “activists”—the former lending credibility to law enforcement’s perspective, the latter serving as controlled opposition to create an appearance of balanced representation.

This framing steered public discourse toward questions of "law and order," while police provocation and systemic reform demands received secondary coverage.

Tone, optics, and strategic packaging become the criteria for coverage, not the gravity of the injustice, nor the credibility of the demands. In essence, the issue isn't whether you're right—it's whether you're palatable to a mainstream audience.

So while a shattered storefront becomes a headline, the systemic violence that led to the uprising is buried in the crawl. The audience is primed to grieve the damage, not the deprivation of justice. They’re permitted to feel fear, not solidarity; to focus on reaction, not cause.

From Framing to Force

While media shapes perception of what’s acceptable, the state delivers punishment—making sure that dissenters not only lose the narrative, but they know the price of resisting. Punishment moves the narrative off the screen and into people’s lives, making the consequences of dissent impossible to ignore.

That cost isn’t just limited to alienation or disaffection—though social ostracization is a common side effect. It extends from the discursive realm into material consequences.

Take, for instance, the case of Mahmoud Khalil, a Muslim American against whom deportation proceedings began nearly two months ago. He’s still sitting in ICE custody without charges.

He isn’t being targeted because his message was incorrect or fallacious. He’s being targeted because of the urgency of his expression—and the refusal to mute it—as a member of the outgroup.

His delivery became the focus, while the subject of his speech—an ongoing genocide—continues to go unacknowledged by the very systems working to enable it.

This is how containment becomes policy. Speech is punished not for being dishonest, but for refusing to sound acceptable.

Compare, if you will, Khalil’s treatment to that of Robert Keith Packer, one of the January 6 rioters recently pardoned by Trump.

Packer is perhaps best remembered as the actual Nazi who was photographed during the riot wearing a black hoodie reading “Camp Auschwitz.” The graphic glorified the infamous Nazi death camp and included the phrase “Work Brings Freedom” at the bottom—a direct reference to the gate at the camp’s entrance.

Packer’s imagery and actions, though widely reported, were reframed as a patriotic misstep—something closer to error than crime. This, ironically, from a government that has worked tirelessly to conflate anti-Israel and anti-Zionist sentiment with antisemitism—a sleight of hand designed to silence resistance to the Israeli genocide the U.S. continues to underwrite.

What happens next is inevitable, if predictable. Mahmoud is made a public example—a tale of woe to anyone who would follow in his footsteps. Communication theorists describe the aftermath as a Spiral of Silence: a chilling effect that takes hold of those who see others penalized, marginalized, or dismissed for speaking out. That risk is internalized, and many begin to self-censor, often without realizing it.

Silence becomes a tactical decision for self-preservation.

Historical Echoes: The Repackaging of Resistance

To be sure, tone policing isn’t new—the practice has long functioned as protocol, especially in political discourse between unequal parties. As long as there has been resistance, there have been efforts to stifle it: to muddy its message, distort its intent, and flip its meaning on its head.

Take, for instance, Martin Luther King Jr., now canonized as a model of civility, but during his life, condemned as a radical agitator. His words were dismissed as dangerous, his tone cast as divisive. Yet in his Letter from Birmingham Jail, King directly addressed this mischaracterization—not to white supremacists, but to white moderates.

As King wrote, the greatest stumbling block to Black freedom was not the Ku Klux Klan, but the “white moderate, who is more devoted to order than to justice.” It wasn’t injustice that bothered them. It was its disruption of the status quo.

Malcolm X, too, was subjected to tone policing—though his treatment carried a different register of erasure. Whereas King was urged to be more patient, Malcolm was cast as irredeemable.

His refusal to perform softness, his insistance on naming white supremacy without euphemism and his rejection of respectability politics made him a target of state surveillance and media caricature.

His anger was pathologized as hate. His clarity, cast as hostility. His demand for dignity was reframed as extremism.

In his 1963 speech "Message to the Grass Roots," Malcolm X used a compelling metaphor to illustrate how Black resistance is often diluted to make it more palatable:

"It's just like when you've got some coffee that's too black, which means it's too strong. What you do? You integrate it with cream, you make it weak. If you pour too much cream in, you won't even know you ever had coffee. It used to be hot, it becomes cool. It used to be strong, it becomes weak. It used to wake you up, now it'll put you to sleep."

Rather than engage with the substance of his message, critics fixated on his tone—treating his delivery as the problem instead of the injustice he named.

Today, both Malcolm and Martin are selectively quoted by institutions that once ignored or condemned them—polished into symbols of progress now that the heat of their messaging has cooled.

This rhetorical laundering doesn’t end with individuals. Once the edge has been dulled and the message defanged, entire movements become ripe for appropriation.

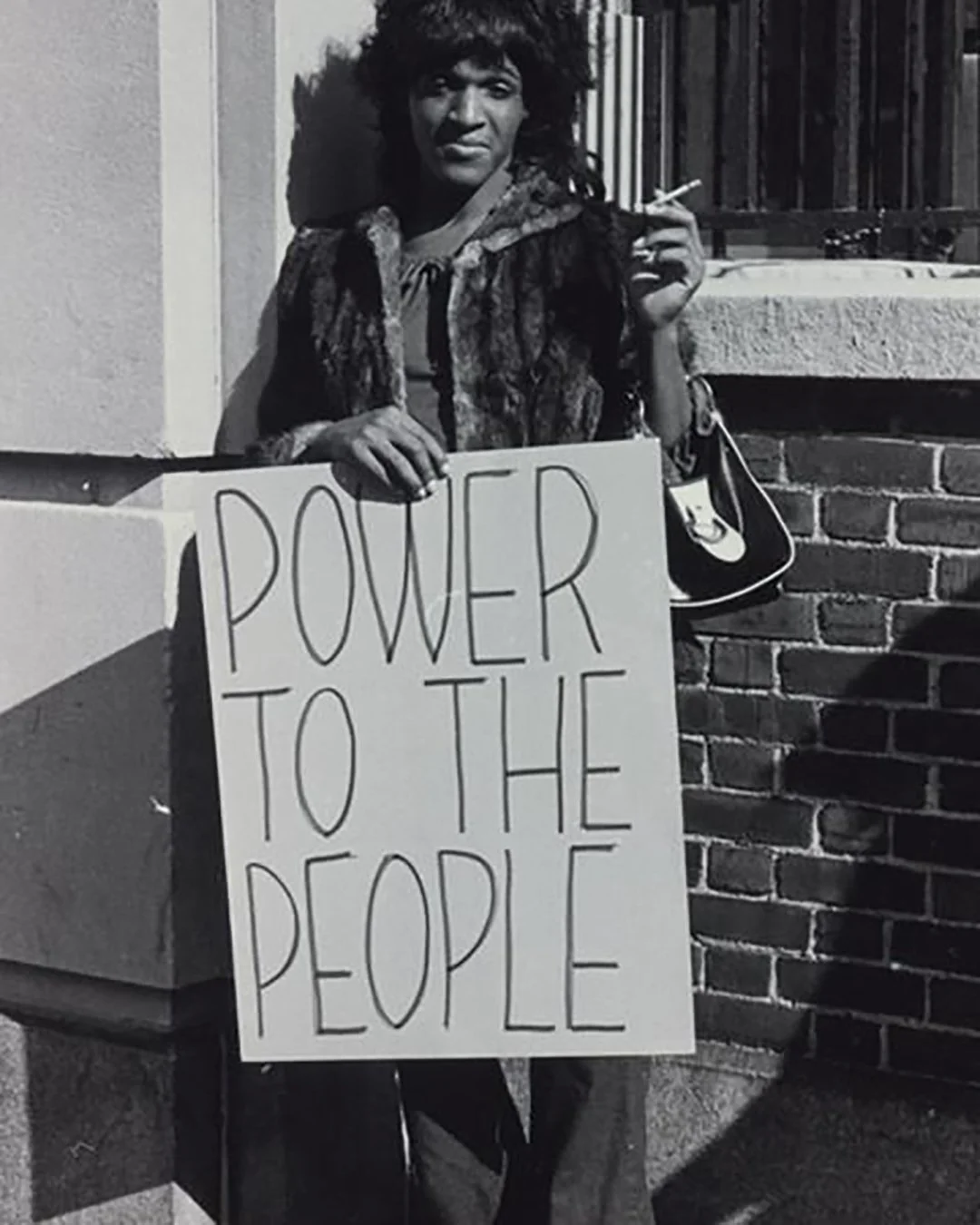

We’ve seen it before: the corporatization of Stonewall, where a riot against police brutality is now paraded with sponsorship banners and rainbow-wrapped police cars; not to mention the pinkwashing of Marsha P. Johnson’s radicalism into marketable pride iconography, her legacy sanitized for comfort while her demands remain unmet. Despite her undeniably integral role as a Black trans woman, commercialization has attempted to remove any semblance of the indelible impact she made for the cause.

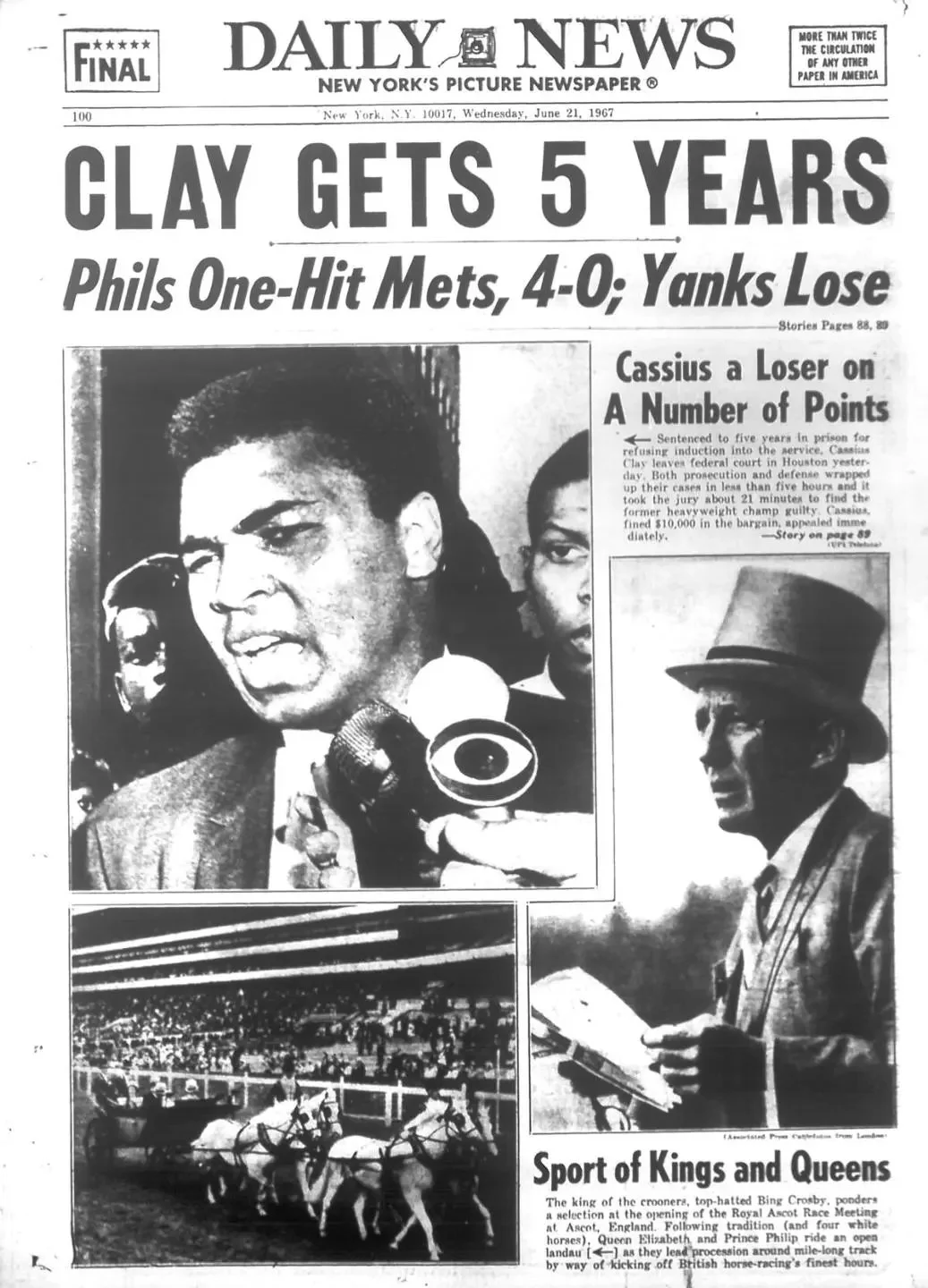

It’s not unlike the case of Muhammad Ali, who was similarly vilified as a traitor and draft dodger for refusing to fight in Vietnam. He was stripped of his titles and banned from boxing. Years later, he would come to be hailed as the humanitarian and civil rights hero still celebrated today.

Let us not forget Nelson Mandela, perhaps the most recognizable figure in the fight for South African liberation. In 1986, he was labeled a terrorist by the United States and other Western nations, and would remain on their watchlists until 2008.

He spent 27 years imprisoned for opposing apartheid—only to be posthumously embraced by those same governments as a symbol of peace and reconciliation.

This is a recurring pattern: the more loudly a voice was silenced then, the more eagerly it is later claimed by the very forces that once worked to erase it—a textbook example of fascism’s practice to repackage what it represses in order to manufacture legitimacy.

Intersecting Silences: Tone Policing at the Margins

As has hopefully been made clear at this point, tone policing does not strike proportionally. It follows the contours of structural power, its sharpest edges landing on those who speak out from the margins.

Expectancy Violations is an area of study that analyzes this disproportionality: communication structured by socially constructed expectations about how people “should” speak based on identity. These expectations are steeped in implicit bias.

A white man raising his voice, for instance, may be seen as impassioned, while a Black woman doing the same is labeled angry, unprofessional, or aggressive. The same volume, the same cadence, the same fervor is judged by different standards, because the expectation was never equal to begin with.

Across marginalized groups, the pattern repeats: for women, justifiable anger is pathologized; for queer and trans communities, defiance is framed as an assault on traditional values; for Black movements, resistance is criminalized; for Indigenous voices, defiance is recast as militancy.

Scholars call this epistemic violence—an erasure of the cultural frameworks those voices carry.

Beyond mere silencing, this is redefinition: lived truth becomes irrationality, emotiveness becomes instability and grief becomes aggression. Each rhetorical expectation is shaped by power rather than through reason or logic.

To speak from the margins is to navigate an ever-shrinking perimeter of tolerance, where expectations become insurmountable, and even justified anger becomes grounds for disqualification. These expectations play out in virtually every aspect of our lives.

Respectability, Facework and the Theatre of Accommodation

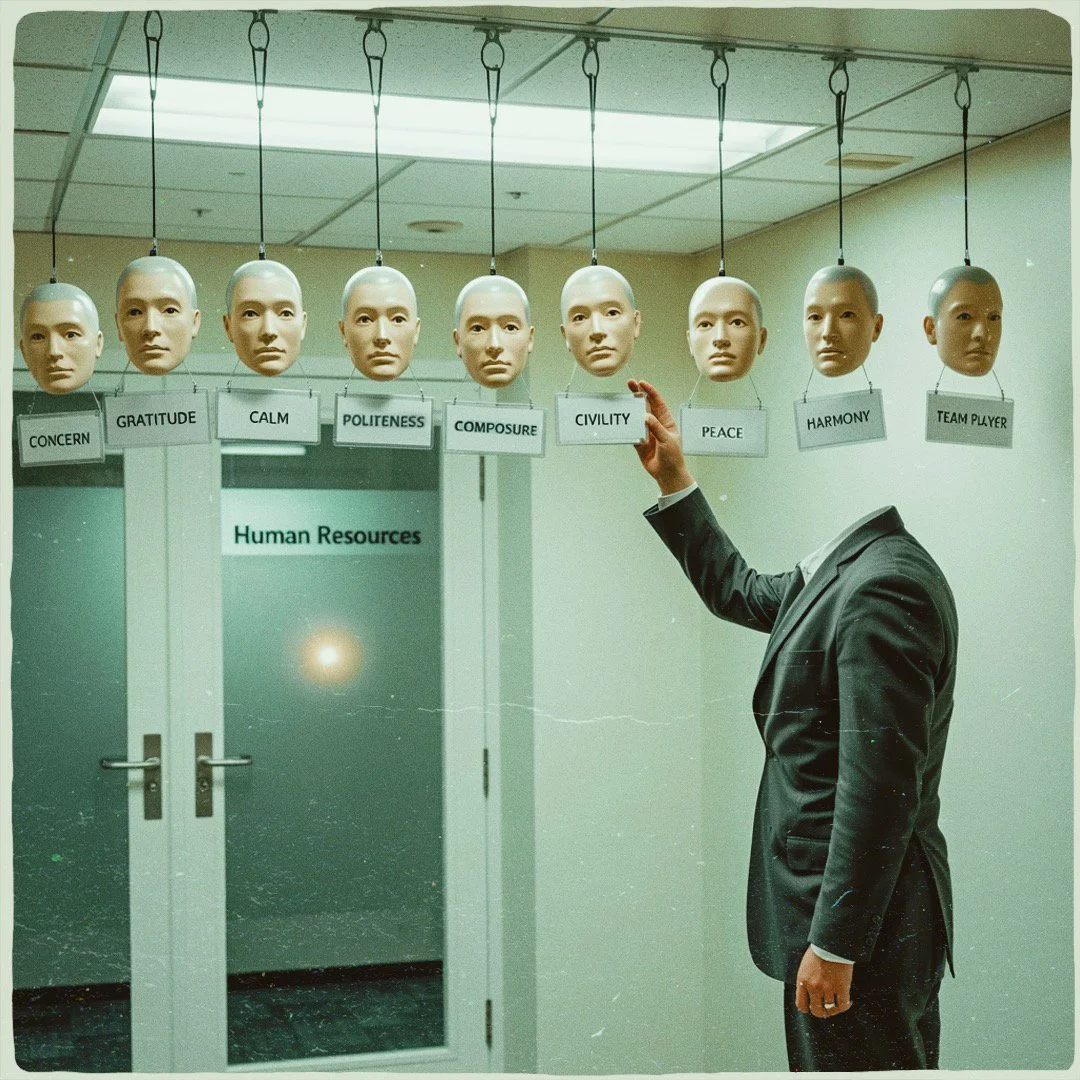

The tone police aren’t always immediately recognizable. Sometimes they show up via the subtleties hidden in HR memos, "culture fit" evaluations, or annual performance reviews.

In these settings, the concept of Facework is useful in describing how people manage impressions to maintain the illusion of homeostasis in organizational environments. In power-imbalanced settings, the brunt of that labor is shouldered by the already-marginalized.

These voices are compelled to regulate their own expressions while also absorbing the emotional reactions of those in authority. They are expected to soften critiques into suggestions, transform anger into concern, and reframe trauma as constructive feedback.

This becomes a type of performative professionalism, a corporate dialect of tone policing. Its enforcement is less about ensuring accuracy and more about surveiling temperament.

Whereas Facework emphasizes managing immediate social interactions to maintain harmony, Communication Accommodation theory exposes how these dynamics scale up—revealing the institutional pressures that force conformity.

Within workplace and organizational environments, marginalized individuals are compelled to recalibrate their communication: adjusting vocabulary, vernacular, even vocalization, to meet dominant expectations.

This pressure builds beyond simply speaking to be heard, to speaking under the constraints of an unfamiliar, often hostile metric. Falling short of these imposed standards risks tangible repercussions: alienation, marginalization, even formal discipline.

Those who resist adaptation are branded aggressive, disruptive, or “not a team player.” Adhering to performance standards—linguistic, emotional, cultural—becomes the price of admission.

Aesthetics of Acceptability

Tone policing doesn’t merely enforce these norms—it aestheticizes them. It transforms power into preference, control into couture, and subjugation into stylization—embedding submission under the guise of good taste.

The standards for this legitimacy are shaped not by objectivity but by taste.

In Critique of Pure Reason, Immanuel Kant establishes that knowledge is filtered through structures that favor certain forms while excluding others—especially those grounded in emotion, intuition, or lived experience.

He would later observe, in Critique of Judgment, that aesthetic prejudices, though subjective, often carry an expectation of universality. We’re taught to prefer certain forms, then conditioned to treat those preferences as reflections of objective, universal truth.

Kant referred to this as “purposiveness without purpose”—a demand for harmony even where none is warranted, or worse, where a moment necessitates the opposite. Insistance on obedience from the oppressed serves only to preserve the comfort of the oppressor.

In modern discourse, these dominant emotional styles—calmness, detachment, temperance—are treated as the basis of legitimacy itself.

This creates a rhetorical double bind for marginalized speakers. They must name harm in a manner that soothes, they must articulate pain with poise. Their legitimacy depends whether or not their grief can be consumed comfortably.

Suppression operates through this conditioning. Dissent is only tolerated when delivered in the emotional vocabulary of power. Anything else is unprofessional. Uncivil. Unheard.

Emotional Terms of Legitimacy

When public discourse demands civility as a precondition for legitimacy—it’s screening speech for tone rather than truth. Indifference and composure are elevated; desperation, grief, and anger are marginalized. Displays of urgency or outrage are reframed as breaches of order, not signals of harm.

Democratic societies enforce this communicative legitimacy less through formal law than through unwritten norms.

The illusion of open dialogue is maintained, but the terms of engagement are quietly rigged. Speech that conforms to aesthetic expectations is treated as credible; speech that violates them is suffocated of air.

In such settings, dissent must conform to be acknowledged. It is not enough to speak truthfully; one must also perform acceptability.

Here, dissent doesn’t need to be wrong to be disqualified—it only needs to sound wrong.

When Resistance Is Choreographed

Within discourse theory, language is never just words—it’s terrain. It’s the surface that platforms rulers—those who determine what’s visible, what’s viable and what’s vulgar.

Thus describes controlled opposition: a curated resistance that offers critique without consequence. It offers the form of challenge without the potential for rupture. Tone policing is its regulator—disciplining not the message, but the messenger’s emotional volume.

As Joel Carberry argues in Mirage of Dissent, controlled opposition isn’t merely tolerated by systems of power—it’s manufactured by them.

These “dissenting” voices are created in the image of the institutions they supposedly oppose—loud enough to be heard, but too diminished to spark change. They act as shock absorbers—cushioning resistance so the machinery can keep running undisturbed.

Sometimes, these figures take the form of absurdist agents: hyper-visible, hyperbolic performers whose caricatured delivery renders the movements they mimic easier to dismiss. They are, for all intents, the painted clowns of speech.

Their outrage is theatrical, circus-like. Their slogans are stripped of substance. They do not push the envelope. They use it to package a neutered version of resistance.

It’s not that they are unaware of the farce. These individuals, some of whom may have started out as sincere idealists, willingly accept the jester’s role.

As Slavoj Žižek observes, “they know very well what they are doing, but still, they are doing it.” That is to say, the absurdity is the point. It’s a performance of critique that reinforces the very structures it claims to challenge.

The appearance of dissent becomes an insurance policy for power—evidence that “debate” is allowed, so long as it doesn’t threaten anything load-bearing.

What follows is an information cascade—a narrative avalanche designed to bury truth beneath spectacle. The collective imitation occurs despite the likelihood of incorrect outcomes.

Public conversation buckles under the weight. Once these voices take the stage, any real resistance begins to look tainted simply for sharing the same rhetorical space as this staged exhibition.

Like trapeze swingers suspended at dizzying heights, they perform the appearance of danger—their safety net hidden just out of view of the enthralled crowd, eliminating any genuine risk.

The crowd watches, amused by the illusion of risk—comforted by the certainty that nothing real will be broken.

When the public tires of the pageantry, the circus leaves town. The audience disperses, bonding over feats of bravery that never really happened.

This is what discourse analysis exposes: language doesn’t reflect power—it rehearses it.

Once sufficiently sculpted, once thoroughly tone policed, language becomes a stage for controlled resistance—frequencies modulated to sound impassioned, but fine-tuned for broadcast to no one.

That’s the final chokehold: resistance rehearsed until it’s harmless, then silenced until it’s sentimental—ready-made for repackaging. Once someone is trained to compulsively self-edit their tone, systems no longer need to censor what’s said—they’ve already taught the speaker how to say nothing.

The most powerful resistance was never meant to be tidy. It was never meant to soothe.

It’s meant to reclaim power.

Reclaiming Expression as Counterpower

Standpoint Theory reminds us: those most affected by oppression often see its architecture most clearly. To them, anger isn’t noise—it’s knowledge.

Rejecting tone policing means reclaiming the full range of political communication—refusing silence as the default, and reasserting the right to confront, to grieve, to seek redress.

The ruling class insists on a model of deliberative democracy that elevates rational dialogue as the highest form of civic engagement. Such arrogance enforces an aesthetic of order that flattens emotion and reinforces the fascist fantasy of a calm, compliant public.

Denouncing these norms can be a form of rhetorical resistance—a means of fighting to preserve authenticity where silence is the expected currency. This means fighting outside of the parameters established by the powerful, and proposing and implementing real and lasting change.

Communication requires more than concessions from one group for the comfort of another; plain and simple. It demands confrontation, equitibility, acknowledgement, validation.

Movements aren’t born at establishment-funded rallies that promote incrementalism. Resistance does not come from focus-grouped performative lip-service. These are forged where desparation overtakes patience, and fury refuses to be restrained.

From Containment to Institutionalization

What happens in interpersonal situations carries weight in organizational settings too. Requests to “lower your voice” or “calm down”—the framing of emotion as a problem—are more than awkward moments.

We may not deport people with our calls for “civility”—no single one of us possesses that power. While tone policing in daily conversation may not carry the force of law, it replicates the logic later enforced by fascist institutions of power.

Every time composure is prioritized over clarity, every time urgency is punished for unsettling the comfortable, the emotional architecture that makes institutional oppression possible is further reinforced.

Participation in that logic requires no badge, no gavel—only the willingness to preserve the frame and maintain the narrative.

Even those who claim to support LGBTQ+ rights, women’s autonomy, anti-colonization efforts, or any number of human rights causes engage in tone policing—ostensibly unaware they’re fortifying the very structures they intend to oppose.

Solidarity becomes conditional, and those conditions invariably derive from conditioned thinking, based on the parameters set in place by those in control. We’ve all engaged in it. Anytime we place our voices above someone less privileged than us (and there's always someone worse off), we uphold the very architecture we claim to resist.

The language of discourse is not neutral. Every tone standard, every speech code, every etiquette rule—these are technologies of power. They shape speech while quietly scripting the terms of inclusion.

So remember: when voices tremble, when they break, when they bellow—this is not collapse. This is resistance reclaiming its voice.

This is what clarity sounds like when it is no longer willing to beg.

It may sound unruly—unrefined, unwelcome, perhaps delivered by someone who’s “a bit much,” or even “kind of a lot” according to those who demand composure from the dispossessed.

Don’t look away. This is not chaos.

As Marsha P. Johnson put it: “I may be crazy, but that don’t make me wrong.”