Chavez Ravine: Forgotten Neighborhoods Beneath Dodger Stadium

The tragic tale of Chavez Ravine reveals the erasure of a vibrant Mexican American community to make way for Dodger Stadium

Picture a vibrant Mexican American community nestled in the hills north of downtown Los Angeles: Chavez Ravine, a thriving haven defined by family bonds, rich traditions, and deep cultural roots.

Now, juxtapose that against the image of Dodger Stadium—a supposedly gleaming monument to American progress and modernity.

Between these two realities lies a story of violent displacement, systemic injustice, and cultural resilience.

Chavez Ravine was a home, a sanctuary, and a testament to the resilience of Mexican American families who had carved out a life on the margins of a city that never truly embraced them.

Before the smell of Dodger Dogs wafted in the air above the Los Angeles skyline, the hills echoed with the laughter of children, the hum of transistor radios, and the warmth of a community forged from shared struggle and deep cultural roots.

That community is long gone, bulldozed in the name of civic progress, capitalist ambition, and the unchecked power of eminent domain.

The displacement of Chavez Ravine’s residents isn’t just a story of urban development. It’s part of a long, uninterrupted history of land theft—beginning with the forced removal of Indigenous peoples, continuing through the stripping of land from Mexican communities, and still unfolding in every gentrified neighborhood where tenants fight to remain.

Before Colonization: Indigenous Land and the Restructuring of Power

Long before the city of Los Angeles, before the Spanish missions, before the treaties and betrayals, the land that became Chavez Ravine was home to the Tongva people.

The Tongva lived in reciprocity with the land, stewards rather than owners, maintaining an ecological balance that had sustained them for thousands of years.

Their relationship with the environment was guided by generational knowledge—practices like seed tending, seasonal harvesting, and the careful maintenance of native landscapes ensured the health and abundance of the region.

That equilibrium was shattered when Spanish colonizers arrived in the late 1700s, enslaving Indigenous populations under the guise of religious salvation.

The missions were not centers of cultural exchange but instruments of forced labor and assimilation. Those who resisted were slaughtered, their villages burned, their children stripped from them.

Following Mexico’s independence from Spain in 1821, the mission system collapsed, but the Indigenous people it had displaced remained landless—forced into servitude or pushed even further to the margins.

After the U.S. annexed California in 1848, the process of dispossession accelerated. Mexican landowners—many of them Indigenous or mestizo—were stripped of their property through fraudulent legal maneuvers, violent coercion, or outright theft.

The promises of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo were swiftly undermined in courtrooms where claimants faced impossible burdens of proof and legal systems designed to fail them.

This dispossession was indicative of a new colonial order, one in which land was systematically transferred from long-rooted communities to those deemed racially and politically fit to inherit the future.

At the same time in Northern California, settlers and state-funded militias were carrying out a campaign of government-sponsored genocide against Indigenous communities—what state officials openly called a “war of extermination.”

The violence wasn’t just tolerated—it was subsidized, with public funds reimbursing citizens for killing Native people. In both the courts and the hills, a racialized regime of land theft and removal was unfolding.

Chavez Ravine, like so many other neighborhoods on the fringes, became a refuge—one of the few places where Indigenous people could live, build, and survive in a city that treated them as unwelcome guests.

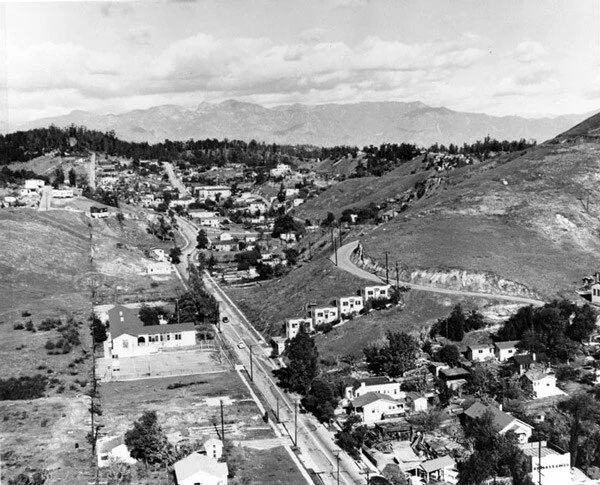

La Loma neighborhood in Chavez Ravine, 1930s

The Rise of Chavez Ravine

The area became known as Chavez Ravine after Julian Chavez, a Los Angeles City Councilman acquired the land in the 1840s—along with much of what would become Elysian Park.

By the early 20th century, Chavez Ravine had grown into a vibrant Mexican American enclave, forged by exclusion and sustained through resilience.

Its three main neighborhoods—Palo Verde, La Loma, and Bishop—became home to families forced out of other parts of Los Angeles by redlining, restrictive covenants, and racist zoning laws.

Just east of these neighborhoods sat Solano Canyon, a fourth enclave often considered part of the larger Chavez Ravine area.

Though it would later escape the full-scale demolition that erased the others, it too bore the weight of municipal neglect, freeway construction, and the creeping encroachment that would culminate stadium infrastructure.

While white suburbia sprawled outward through subsidized highways and FHA-backed mortgages, Mexican American families were left to carve out space in the steep, unpaved ravines that no developer wanted—until they did.

The families of Chavez Ravine built an entirely self-sufficient community on the fringes of a city that had turned its back on them. Despite the absence of paved roads, sewers, or basic infrastructure, the community endured.

The neglect was no accident. It followed a premeditated pattern of policy decisions that deliberately withheld investment, creating the very conditions later used to justify removal.

Homes were self-built, water was often carried in by hand, and services were scarce by design. What emerged wasn’t slum but sanctuary: backyard gardens, chickens, fruit trees, and churches that doubled as community centers.

This wasn’t a community that simply existed—it was one that persisted. Schools, tiendas, and intergenerational homes formed the infrastructure of survival, built in the shadow of a city that deemed its residents disposable.

It all unfolded against the backdrop of a federal government actively engaged in mass-deporting hundreds of thousands of people of Mexican descent—many of them U.S. citizens—through mass repatriation programs in the 1930s and, later, Operation Wetback in the 1950s. The message was consistent: you may live here, but you are not welcome.

The very act of staying became a form of resistance.

Los Angeles—shaped by speculative real estate and a thirst for expansion—would not leave Chavez Ravine untouched. As the city sprawled outward, it also looked inward, setting its sights on the land Mexican Americans had managed to hold.

The same forces that once confined families to the Ravine would now conspire to displace them in the name of modernization.

Postwar Los Angeles and the Machinery of Urban Renewal

After World War II, Los Angeles was on the precipice of transformation. With federal funding pouring in for infrastructure projects, city planners sought to reshape the urban landscape.

The Housing Act of 1949 promised modernization, but for communities like Chavez Ravine, it meant one thing: displacement. The Los Angeles City Housing Authority declared the area a prime site for “redevelopment.”

The plan? Demolish the so-called substandard housing in Chavez Ravine and replace it with Elysian Park Heights—a sprawling public housing complex designed by famed architects Richard Neutra and Robert Alexander.

The project was pitched as a solution to “urban blight,” a way to uplift working-class families. However, the city’s definition of blight had little to do with infrastructure and everything to do with race.

Neutra and Alexander’s design reflected a modernist ideal—sleek residential towers, open courtyards, and communal amenities built to engineer better living through architecture. Yet their vision, like many born from high-modernist planning, imagined the land as a blank slate.

Rendering of Neutra’s and Alexander’s vision to replace Chavez Ravine

The families of Chavez Ravine, and the culture they’d cultivated over generations, were simply not part of the blueprint.

There was no public reckoning with the fact that uplifting one vision of housing meant destroying another that had already taken root. As with so many instances of top-down planning, the supposed good intentions of progressive architecture became complicit in displacement.

Officials branded Chavez Ravine’s homes as dilapidated, despite the fact that many were well-maintained and owned outright by their residents. The underlying problem—one that was left unspoken—had nothing to do with the condition of the homes; it was about who lived in them.

The erasure didn’t begin with bulldozers—it began, as many colonization efforts do, with language. Those in power framed Chavez Ravine as blighted, unfit, underused—inflicting harm while framing it as protection.

The rhetorical strategy was familiar. Across the country, so-called “urban renewal” programs used blight as a pretext to displace Black neighborhoods under what James Baldwin and others called “Negro removal.”

A 2011 report by the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights highlighted how this framing justified the systematic destruction of African American communities in the name of progress.

Chavez Ravine followed the same script. What officials called revitalization was, in practice, the removal of working-class Mexican American families—replaced not by housing, but by a stadium, a parking lot, and a profit model.

In doing so, they constructed the oldest settler lie: that this was a land without a people. From there, the land could be claimed, cleared, and sold—without accountability and without memory.

Using eminent domain, the city began acquiring property, forcing families to sell at prices far below market value. Residents were promised priority housing in the new development, but as political tides shifted and anti-communist hysteria took hold, the project was scrapped. The land, stripped from its rightful owners, sat empty.

And then, the Dodgers came knocking.

Propaganda flier for Proposition B, which would result in a victory for Dodger Stadium

The Dodger Stadium Deal and the Final Betrayal

In 1957, Los Angeles officials, desperate to bring Major League Baseball to the city, struck a deal with Brooklyn Dodgers owner Walter O’Malley.

They offered Chavez Ravine as the future home of the Dodgers, despite the fact that the land had been taken, its people displaced, under the pretense of public housing.

What had once been a promise of affordable homes for working-class families was now little more than a bargaining chip in a high-stakes game of political maneuvering and economic ambition.

The justification was dressed in the language of civic progress.

City leaders claimed that a major league team would elevate Los Angeles into the ranks of world-class cities, bringing prestige, tourism, and economic growth. But the reality was far grimmer for those who still lived on the land.

While deals were made behind closed doors, the remaining residents of Chavez Ravine—many of whom had already been pressured into selling their homes for pennies on the dollar—were left to watch their community’s fate decided by a ballot they had no power to influence.

A citywide referendum, known as the "Dodger Vote," sealed their fate. Officially titled Proposition B, the 1958 measure asked voters whether the city should transfer Chavez Ravine land to the Dodgers.

Brooklyn Dodgers owner Walter O’Malley

While framed as a democratic process, the vote obscured the reality that the land had been acquired under the false pretense of public housing, not private development.

The campaign in favor of the deal was built on strategic misinformation, portraying the stadium as a necessity for the city's future while downplaying or outright ignoring the human cost.

Civic leaders framed opposition as anti-progress, dismissing those who resisted as obstacles rather than people fighting for their homes. The measure passed, giving city officials the final legal justification to do what they had long planned—erase Chavez Ravine from the map.

For the families who had refused to leave, the reckoning came swiftly. In 1959, the last remaining residents were forcibly evicted in what became known as “Black Friday.” It was not a quiet administrative process—it was a spectacle of state violence. Police officers, armed with batons, dragged men, women, and children from their homes.

Families clung to doorways, to furniture, to any last vestige of their lives in a desperate attempt to resist the inevitable. The sound of bulldozers reverberated through the hills as homes were torn apart before their owners' eyes.

The iconic image of Aurora Vargas being carried away by officers as she kicked and screamed encapsulated the brutality of it all. But for every Vargas caught on camera, there were dozens more whose anguish went undocumented, their histories reduced to rubble alongside their homes.

When the dust settled, the land stood empty, its former residents scattered across the city with nowhere to return. The community was gone, the final echoes of its existence buried beneath the foundations of a stadium that would soon rise in its place.

Construction on Dodger Stadium soon commenced, and with its start, so too began an official rewriting of history—one that would conveniently omit the people who had been sacrificed for the sake of its creation.

The Stadium That Stands on Stolen Land

Dodger Stadium opened in 1962, celebrated as a triumph of sports and civic pride. Its construction was hailed as a step forward for Los Angeles. But beneath the concrete, beneath the perfectly manicured field, lay the buried memories of a community that had been sacrificed in the name of progress.

“There’s an old Mexican custom that where you’re born, the umbilical cord is buried. Mine’s buried under third base . . . . And I hate home runs, ’cause every time they step on third base, my stomach hurts”

– Lou Santillan, former resident of Chavez Ravine

Today, Chavez Ravine’s history is reduced to a footnote—an unfortunate but necessary consequence of development. But for those who lost their homes, the wounds have never healed. The fight for historical recognition continues, with advocates calling for reparations, memorials, and accountability for the injustices committed.

Yet, the machinery of displacement is still at work. The same justifications that erased Chavez Ravine are now used to push out families in Boyle Heights, Echo Park, and countless other neighborhoods—not just in Los Angeles, but in cities across the country.

From Five Points in Denver to Williamsburg in Brooklyn, from the West Side of Chicago to East Austin, redevelopment projects cloaked in the language of progress continue to displace working-class communities of color under the banners of investment, revitalization, and growth.

No community is safe from this systemic erasure. What’s marketed as urban renewal often amounts to cultural erasure—bulldozing not only homes but histories, severing people from place, culture from concrete, to make room for increased profitability.

The same forces that prioritized a stadium over homes continue to shape policy, favoring corporate interests over the lives of those deemed disposable by design.

The tale of Chavez Ravine’s displacement is more than a story of a ballpark. It’s about power—who has it, who doesn’t, and what happens when those without dare to claim a piece of land as their own.

All We Have are Stories

From the Tongva, ousted by the Spanish, to Mexican landowners stripped of their property after 1848 and the Chicano families bulldozed out of their homes in 1959, the pattern remains the same.

Communities deemed inferior through the lens of white supremacy are reduced to naught more than property lines and deeds, their histories, and traditions, tossed asunder.

Still, their stories persist long after the structures that housed them are reduced to dust.

Meanwhile, the modern normalization under which ballpark-goers— including many Mexican-Americans—enjoy “America’s Pastime” seems to have all but erased the trauma the land below still carries.

Ultimately, Dodger Stadium may stand as a monument to baseball, but for those who know its history, it is also a gravestone that marks the life of a community.

The price of its construction was not just measured in concrete and steel but in the shattered bonds of a neighborhood that was once alive with laughter, music, and the warmth of multigenerational families.

The streets where children played, where neighbors gathered for fiestas and shared meals, were buried beneath the stadium’s foundations.

Chavez Ravine was stolen. Its people were erased. Yet its memory refuses to be silenced. It lingers in the echoes of old foundations, in the photographs tucked away in family albums, in the stories passed down through generations.

It exists in the quiet moments of recognition when descendants of those displaced walk past the stadium, knowing that their families once called this place home.