Fear of a Red Planet: America’s Unhealthy Obsession with Communism

America’s fear of communism has fueled wars, coups, and repression both abroad and at home, shaping policy and silencing leftist movements.

For more than a century, the United States has waged war on communism, portraying the economic philosophy as an existential threat to its own corporate–state power.

From the moment the Bolshevik Revolution sent tremors through the world, the American establishment seized on the “Red Scare” as a unifying fear tactic.

Official rhetoric adorns this ideological crusade in the language of democracy, liberty, and human rights.

In reality, it serves as the camouflage of an empire, running cover for international coups and domestic repression.

The historical record is clear: any time a nation has acted to nationalize resources, redistribute wealth, or place human needs above the demands of foreign capital, it is targeted by the U.S. for political isolation, economic sabotage, or outright destruction.

Meanwhile, American citizens nod their heads in agreement; this is the right decision. The will of the State must not be questioned.

Much like the religion passed down by the colonizers that comprise White American ancestry, politics, too, have been absorbed most uncritically — beliefs inherited rather than examined.

Thus the gospel, written through this generational game of telephone, is established:

To be American is to be anti-Communist. No scrutiny of facts required — just dogmatic, obedient compliance, like that with which the nation’s children pledge “allegiance” without even knowing what it means to be allegiant.

As a result, entire generations are taught to be fearful of communism, never questioning who that fear serves.

-

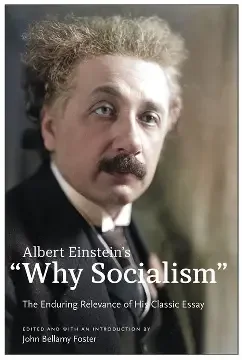

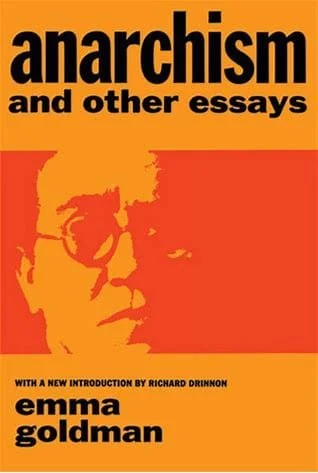

Communism, socialism and anarchism are often used interchangeably in American discourse—a conflation of meaning rooted more in Cold War propaganda than in honest political study.

While these ideologies each share a common aim: to end exploitation and build a world where dignity isn’t contingent on wealth or hierarchy, they embody a vast array of different traditions and strategies regarding how to achieve that end.

What unites them is a refusal to accept that suffering is inevitable, and a belief that collective liberation is not only possible, but necessary.

With that in mind, this article might as easily be called “America’s Fear of Leftism”—it references these ideas from the perspective of an American public who view any leftist thought as part of the amorphous blob that lives in the collective amygdala as “communism.”

How Did We Get Here? Thought Crime as Sedition

Even before the Cold War, the United States had begun laying the legal groundwork to neutralize what it perceived to be radical politics.

Congress passed sweeping criminal syndicalism laws, and the courts overwhelmingly upheld them, cementing a precedent that political ideology itself could be treated as a threat to national security.

The first test came in Schenck v. United States (1919). Charles Schenck, general secretary of the Socialist Party, had distributed leaflets urging resistance to the military draft.

He was prosecuted under the Espionage Act of 1917 and convicted.

The Supreme Court upheld his conviction, with Justice Holmes writing that speech presenting a “clear and present danger”could be restricted — famously using the example of “falsely shouting fire in a crowded theater.”

Another early example was the case of Eugene V. Debs, a Socialist Party leader who’d served in the Indiana House of Representatives.

In 1918, Debs was arrested under the Sedition Act for delivering a speech condemning U.S. participation in the war and urging workers to resist the draft.

Like Schenck before him, the Supreme Court upheld Debs’ conviction under the “clear and present danger” doctrine. In fact, the doctrine would be invoked for decades to come.

Debs was sentenced to 10 years in prison, but his sentence was commuted by President Warren Harding in 1921.

Later, in the same year Debs was decided, the Abrams v. United States case exemplified the same logic.

Jacob Abrams and a group of Russian-immigrant unionists were arrested for distributing leaflets condemning American military intervention against the Bolsheviks in Russia.

The leaflets urged workers to strike in protest. There was no diabolical plot, no violence, just printed words.

Still, Abrams and his co-defendants were convicted under the 1918 Sedition Act and sentenced to up to 20 years in prison.

The Supreme Court upheld the convictions, once again invoking “clear and present danger.”

A few years later, Gitlow v. New York, the story was the same.

Incidentally, Benjamin Gitlow was a former New York state legislator and member of the Socialist Party’s left wing.

The son of Russian Jewish immigrants, he became deeply involved in the labor movement at a young age. In 1914, he testified before the U.S. Commission on Industrial Relations, and exposed exploitative conditions in department stores.

His testimony detailed overtime abuses, management surveillance of workers, and even quid pro quo sexual harassment faced by female workers.

This testimony was part of Gitlow’s broader organizing efforts, which also included helping to form the Retail Clerks Union—known today as the United Food and Commercial Workers (UFCW).

The State’s hostility toward leftist ideas is evident in its opposition to organized labor.

Union movements — driven by socialist and communist ideals — demanded rights capitalism had never provided for its working class.

The eight-hour day, the weekend, child labor laws, workplace safety standards, and the right to collective bargaining were all won through struggles branded by the state and employers as “radical” or “subversive.”

Gitlow entered politics at the age of 18, serving as assemblyman for the 141st New York State Legislature.

Then, in 1919, he published the Left Wing Manifesto, which called for mass strikes and the dismantling of capitalism.

Gitlow was convicted and sentenced to ten years in prison.

There was no evidence of an imminent uprising, but New York’s Criminal Anarchy Law made the mere advocacy of such ideas a crime.

Nevertheless, the Supreme Court upheld his conviction, invoking a “bad tendency” doctrine, dictating that speech could be punished if it had a natural tendency to incite unlawful acts, even without a realistic prospect that those acts would occur.

Taken together, these cases created a legal climate where so-called revolutionary speech could be criminalized on the basis of speculation alone.

Put simply, the government no longer needed direct links between words and deeds; thoughts and ideas were now enough to warrant imprisonment.

Did you know? In the early 20th century, the Russian Empire was home to the world’s largest Jewish community, numbering around 5 million people. While most lived in poverty and under heavy restrictions in the Pale of Settlement, a significant contingent became active in socialist, communist, and anarchist movements. Many we part of a Bolshevik contingent whose outsized role helped shape revolutionary currents across Russia and beyond.

HUAC and McCarthyism: Spectacle and Statute in Service of Suppression

By the time anti-communist frenzy took hold a generation later, the machinery for criminalizing leftist thought was already well-oiled.

Launched in 1938, the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) was created under the pretense of investigating “subversive activities.”

On paper, that included fascist sympathizers and Nazi collaborators—especially relevant given the global rise of Hitler’s Germany during that time.

In practice, however, HUAC became a political weapon wielded almost exclusively against the left.

Its first chairman, Martin Dies Jr., wasted little time on fascist or pro-Nazi groups. Instead, he immediately targeted leftist organizations, New Deal programs, and labor unions.

Even when the Ku Klux Klan came up as a potential subject of investigation in 1946, the committee declined to pursue it.

Mississippi Rep. John Rankin defended the decision by declaring, “After all, the KKK is an old American institution.”

Such moments made clear where HUAC's allegiances lay.

The real threat, in their eyes, was not white supremacy or domestic terror—it was socialism, labor militancy, and solidarity across race and class lines.

By the 1940s, national attention had shifted almost entirely to the hearings of communists and left-leaning labor organizers. This culminated in a theatrical peak in the form of McCarthyism in the 1950s, with Senator Joseph McCarthy enjoying his moment in the sun.

McCarthy, who served no formal role in the HUAC, launched a wave of Senate hearings targeting alleged communists—often based on rumor, innuendo, or forged documents.

The hearings were televised affairs, with McCarthy starring as key interrogator, captivating and terrifying the public, and transforming anti-communism into mass spectacle.

Careers collapsed under the weight of public accusation, being merely named in a McCarthy hearing became a sentence of professional exile.

Blacklists circulated through Hollywood, universities, and unions, ensuring that those branded “un-American” would struggle to find work for years, if they ever worked again.

The State had successfully created an environment where fear did the work of censorship, and where the boundaries of acceptable thought narrowed to fit within the frame of government-approved ideology.

A venomous blend of anti-Semitism, anti-communism, and white supremacist paranoia fueled campaigns to discredit Hollywood as a hotbed of “un-American” influence.

COINTELPRO: Covert War on the American Left

By the 1960s, repression no longer needed a courtroom or a witness stand.

The FBI had refined its tactics into a clandestine campaign known as COINTELPRO — short for Counterintelligence Program — a bureaucratic anagram that masked its true purpose: to “expose, disrupt, misdirect, discredit, or otherwise neutralize” movements that challenged the political and economic status quo.

Black liberation groups, Indigenous activists, antiwar organizers, and socialists were all treated as internal enemies.

The Black Panther Party

The Black Panther Party became the FBI’s top target after it demonstrated a functioning alternative to the state.

It organized around an unapologetic demand to end police brutality and built systems of mutual aid that met community needs without reliance on capitalism or state institutions.

The Panthers’ community programs were systems of mutual aid, built on Malcolm X’s call for dignity, self-defense, and working-class unity across race and gender.

Rooted in Marxist principles that view food, housing, and healthcare as human rights, these initiatives included free medical clinics, clothing drives, and the well-known breakfast program, which fed thousands of children across the nation every week.

In the eyes of the state, that was more dangerous than rhetoric — it was proof that communities could govern and care for themselves without capitalist or state oversight.

Fred Hampton, the Panthers’ 21-year-old Illinois chairman, embodied this threat. He was building alliances across race and class, uniting poor Black, white, and Latino communities into a coalition that could not easily be divided.

Then, in 1969, after an FBI informant supplied a detailed floor plan of Hampton’s apartment and drugged his drink, Chicago police stormed his home before dawn. He was shot dead in his bed.

His assassination was not an isolated act but part of a wider campaign to dismantle the African American freedom struggle.

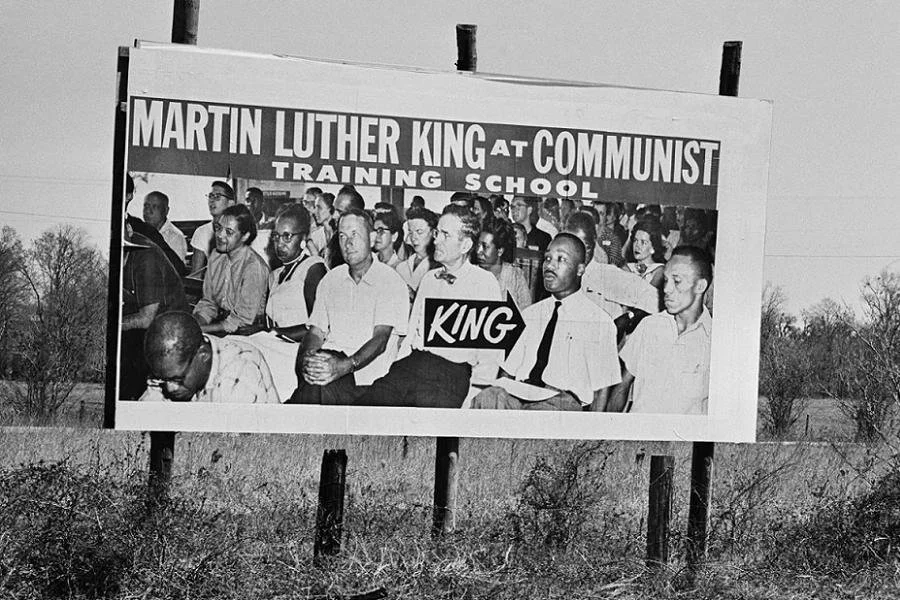

Subversive propaganda attempting to negatively link Dr. King to Communism

In the same decade, other revolutionary voices — among them Malcolm X in 1965 and Martin Luther King Jr. in 1968 — were cut down in the prime of their advocacy.

These high-profile killings demonstrated that COINTELPRO’s logic extended beyond surveillance and disruption, effectively sanctioning the killing of leaders whose ability to mobilize the poor posed a greater threat than any foreign ideology.

The American Indian Movement

The American Indian Movement (AIM), which organized survival schools, community patrols, and high-profile occupations to protest broken treaties and systemic neglect, quickly found itself under the same surveillance, infiltration, and disruption tactics.

The 1973 occupation of Wounded Knee was met with militarized force, which escalated the situation and culminated in the assassination of Lawrence “Buddy” Lamont, a Vietnam veteran who, as Mary Crow Dog put it, “received his honorable discharge from the Marine Corps just about the time a government bullet killed him.”

In the wake of the standoff, years of harassment and prosecutions followed.

Leonard Peltier, an AIM activist, was convicted of killing two FBI agents after a controversial trial that bore the hallmarks of COINTELPRO tactics.

Finally, after fifty years of imprisonment, Peltier had his sentence commuted by an outgoing President Biden, and he was released to spend his last years at home.

Peltier’s statement was one of resilience. "They may have imprisoned me but they never took my spirit!" he said, adding "I am finally going home."

Still, his decades in prison stand as an enduring symbol of how the U.S. criminal legal system is weaponized to neutralize dissent.

Further, Peltier’s imprisonment is one example of how vengeful the U.S. can be when it wants to hold a grudge; it will take a lifetime away from a person out of spite.

Ultimately, COINTELPRO had little to do with actually safeguarding democracy.

Instead, its concentrated efforts safeguarded empire, leveraging constitutionality to suffocate movements rooted in collective power before they grew strong enough to challenge the state.

Capitalism’s Real Enemy: Economic Independence

The same U.S. government that infiltrated and dismantled domestic movements for liberation, also exported its counterinsurgency playbook abroad.

What tied the two together was the logic of preservation: any challenge to America’s racial or economic hierarchy — whether in Oakland or Tehran — was treated as an existential threat.

For Washington, communism’s gravest offense was never its rhetoric about class struggle or even its conflation with authoritarianism.

The U.S. had long propped up brutal dictatorships when it suited its interests, and even today has no moral qualm continuing to do so.

The case of Iran made clear what the unforgivable sin was.

In 1953, Prime Minister Mohammad Mossadegh moved to nationalize the country’s most precious resource: oil. For the first time in history, it seemed, profits from Iranian oil would benefit the Iranian people.

That decision was intolerable to British and American interests, and so was answered with a CIA-backed coup.

Mossadegh was ousted, and the monarchal dictatorship of Shah Reza Pahlavi was restored. Once again Iran became tethered to foreign capital, under authoritarian oppression.

One year later, Guatemala faced the same fate. Jacobo Árbenz, a reformist president, attempted to redistribute idle land owned by the U.S.-based United Fruit Company.

His land reform was modest, intended to empower small farmers, but it challenged the stranglehold of a corporate empire.

In response, the CIA cooked up a covert coup, codenamed Operation PBSUCCESS to oust Árbenz and replace him with pro-U.S. and anti-communist Carlos Castillo Armas.

Using psychological warfare, blockade, and U.S.-trained and -funded forces behind him, the coup toppled the Árbenz regime.

Castillo Armas, a pliant strongman swiftly outlawed leftist parties, immediately reversed all progressive reforms, and returned confiscated land to United Fruit.

His dictatorship plunged Guatemala into decades of extrajudicial killings, disappearances, and genocide of the Mayan people.

Cuba’s fate followed soon after.

Washington had long backed the dictatorship of Fulgencio Batista, a corrupt strongman who opened the island to American sugar monopolies, corporate profiteers, and mafia syndicates while violently repressing dissent.

When Fidel Castro’s revolution ousted Batista in 1959, it nationalized U.S.-controlled industries, and declared education and healthcare universal rights, the crime, again, was economic independence.

Cuba’s defiance turned it into a permanent target of sanctions, sabotage, and invasion attempts, from the Bay of Pigs to Operation Mongoose, and an embargo that continues to this day.

Then, in 1965, Indonesia marked an even darker turn.

With covert U.S. support, General Suharto led a campaign of mass killings following an alleged coup attempt blamed on communists. What followed was one of the bloodiest purges of the 20th century.

Between 500,000 and one million people — members of the Communist Party, labor organizers, peasants, teachers, and even suspected sympathizers — were slaughtered.

The CIA supplied lists of thousands of names to the Indonesian military, monitored the killings in real time, and celebrated Suharto’s rise as a Cold War triumph.

This campaign became known as the Jakarta Method: a blueprint for annihilating leftist movements through mass murder, disappearances, and terror — exported across Latin America and beyond.

Chile saw the method carried into the 1970s. Salvador Allende, elected president through democratic process, attempted to chart a path toward socialism via ballots rather than bullets.

He nationalized copper, expanded healthcare and education, and sought to free Chile from foreign servitude.

The United States responded with propaganda campaigns, economic sabotage, and support for a military coup.

Allende reportedly died by suicide during an assault on the presidential palace, and General Augusto Pinochet subsequently installed a dictatorship that fused terror with neoliberal economics.

In each of these cases, the crime was not violence or tyranny. The unforgivable offense was independence.

Any leader who dared to place the needs of their people above the dictates of Western corporations or State power were treated as enemies of freedom and targeted for elimination.

Evil Empire and the Inversion of Culpability

By the time Ronald Reagan declared the Soviet Union an “evil empire” in 1983, decades of engineered fear had already been hardwired into the American psyche.

In his fateful speech, he cast the Cold War as a biblical struggle between good and evil, speaking out to an evangelical base already taught to see the world in such binary terms.

This framing tapped into a deep reservoir of moral absolutism—one that positioned America not just as a political rival to the Soviet Union, but as the righteous champion of divine purpose.

It was an audacious performance of preemptive victimhood in which the “shining city on the hill” — incidentally, the only nation to have waged nuclear war on humans — recast itself as the potential target of annihilation at the hands of its WWII ally.

This calculated redirection of fear turned attention away from America’s own capacity for mass destruction and toward a carefully crafted external enemy.

The shift allowed the state to present its militarism as defensive rather than aggressive, and its control over public life as a necessary shield against existential threat.

From the early days of the Cold War, the same country that incinerated Hiroshima and Nagasaki trained its own children to dive under desks in futile “civil defense” drills. This conditioned them to believe annihilation was inevitable and that safety depended on unwavering loyalty to the state.

These Pavlovian drills functioned as direct indoctrination, normalizing the idea that survival was contingent on obedience.

Children practicing ‘duck and cover’ drills beneath their desks—ritualized fear conditioning masked as civil defense. The Cold War wasn’t just fought in boardrooms and battlefields, but in classrooms and children’s minds.

That same logic—the linking of safety to conformity—was already embedded in the nation’s legal and political culture long before the Cold War began.

By the time nuclear panic became part of daily life, the machinery to silence political dissent was well in place.

Fear as Doctrine: The Emotional Infrastructure of Empire

To justify endless war against an idea, the United States cultivated and maintained a state of permanent fear among its citizens.

Anti-communism was a policy that became a full-blown national identity; a civic religion grounded in paranoia.

This emotional infrastructure—the ubiquitous sense that America is constantly under siege—is a long employed technique which allows the State to expand its authority under the guise of protection.

At virtually any point throughout history, the threat of imminent attacks on freedom has kept Americans on edge and in line.

Perpetual conflict is effective in manipulating public opinion, which could be why, in its 249 years as a nation, it’s been engaged in military campaigns for 232—a staggering 93 percent of its existence.

This, in a world where the United States maintains approximately 877 military bases across 95 of the planet’s 195 nations—nearly half the world—supposedly necessary for its continued ‘freedom.’

If anti-communism is America’s civic religion, then propaganda is its catechism.

In Angola, former CIA officer John Stockwell oversaw that doctrine’s enforcement—not with sermons, but with fabricated news, staged photographs, and a distribution network designed to make lies untraceable.

His account lays bare the mechanics of manufacturing a moral panic—not by exaggerating real events, but by inventing them entirely.

From laundering fabricated stories through cooperative foreign governments to planting them in major Western outlets, Stockwell details how the U.S. built a narrative of communist savagery on a foundation of pure invention.

The atrocities described by Stockwell never happened. Nevertheless, they appeared in newspapers around the world, attributed to phantom journalists , complete with staged photographs to give them credibility.

John R. Stockwell, a former CIA officer who led U.S. covert operations in Angola in 1975, later resigned and exposed those policies in his book In Search of Enemies.

This disinformation campaign was designed to collapse communism into a caricature of bloodlust, and it didn’t end with Stockwell.

In 1977 Rolling Stone published Carl Bernstein’s exposé, revealing that more than 400 American journalists had secretly carried out assignments for the CIA, shaping news coverage to align with U.S. foreign policy objectives.

The repression of leftists has never been confined to foreign policy. At home, too, the names and tactics have changed but the intent remains constant.

Eugene Debs was jailed for opposing war, Jacob Abrams deported for radical speech, Benjamin Gitlow imprisoned under sedition laws.

From Blacklists to Ballots

Where radicals once faced prison cells and deportation orders, today’s leftists are disciplined through quieter means—endorsements revoked, reputations smeared, and campaigns undercut before they can take root.

Not long ago, Democrats marched in lockstep under the mantra: VOTE BLUE NO MATTER WHO. Party loyalty was expected of every constituent regardless of the candidate.

Now, as a new generation of progressives demands something deeper than symbolism, the knives have come out.

David Hogg—once celebrated as a movement leader—was unceremoniously pushed out of his DNC leadership role after daring to criticize the party’s moral decay.

In New York, Zohran Mamdani, a Muslim democratic socialist with a loyal grassroots base, became the target of Islamophobic smears painting him as foreign and dangerous after winning his primary.

In Minneapolis, Omar Fateh had his Democratic–Farmer–Labor endorsement stripped for a “procedural” issue that wouldn’t have changed his surpassing the 60 percent necessary to win the endorsement.

However critics, including Fateh himself, view this as an attack on his campaign by party insiders, who see him as a direct threat to party orthodoxy.

All of this, from the same party that successfully contained Bernie and reined in AOC, both of whom were once-promising darlings of democratic socialist values. Now, they’ve been reduced to conciliators deployed to soothe dissent against establishment corruption and normalize the increasingly authoritarian drift of the party.

It appears that the fear that once justified the prosecutions of radicals in the 1920s and 30s, and the Cold War blacklists that followed, now justifies the quiet purging of socialists in the 21st century.

At any cost, through any means, the mandate endures: prevent the public from ever seriously engaging with ideas that threaten corporate dominance and the foundations of the American empire.

Communism Without the Scarecrow

Strip away that manufactured hysteria, and communism is not a shadowy plot to destroy freedom — it is an economic and political philosophy rooted in a logical principle: those who create wealth should collectively control it.

In its purest form, it envisions a classless, stateless society where exploitation is impossible because there are no owners and no owned.

That vision has never been fully realized, yet wherever elements of it have been allowed oxygen—however briefly—they have consistently expanded human dignity.

Universal healthcare, public education, paid family leave, and workplace safety standards — pillars of modern life — all have their origins in socialist and communist movements.

Many of the federally protected worker’s rights themselves were won through application of ideas the state once branded “subversive.”

History’s most striking glimpses are visible when these ideas were briefly allowed to take root.

The Promise and the Siege

In the first years after the 1917 Russian Revolution, before foreign invasions and blockades strangled it, the new Soviet state legalized divorce, expanded literacy at an unprecedented scale, recognized women’s political and health rights, and redistributed land.

Workers’ councils directly influenced governance, and vast industries shifted to collective control. These were not abstractions — they were lived transformations.

Then, Western powers invaded Russia with 14 different armies, blockaded food and medicine, and backed counterrevolutionary forces during those fragile early years.

To be sure, much of the repression and authoritarianism that followed was forged within this context of incessant besiegement—an aspect seldom present in Western narratives.

Transforming the social order in service of the people proved nearly impossible amid the resulting civil war fueled by counterrevolutionaries and sustained Western intervention, conditions that turned ideals into survival and vision into vigilance.

The Struggle and the Triumph

Elsewhere, however communism’s imprint has endured in spite of proactive efforts to thwart it.

In Vietnam, for example, socialist land reforms and state-led development under the Đổi Mới reforms of 1986 reduced extreme poverty from over 70 percent in the 1990s to under 3 percent today, while raising literacy, life expectancy, and healthcare access even under embargo.

In Kerala, India, decades of communist governance built literacy rates and life expectancy far beyond the national average, proving that even within a democratic framework, socialist policy could deliver where capitalism fails.

In Grenada, Maurice Bishop’s short-lived socialist experiment lifted literacy, expanded healthcare, and built infrastructure at record speed — until U.S. troops ended it.

In Finland, socialist agitation and labor organizing in the early 20th century culminated in a brutal civil war in 1918, when the socialist Reds were violently suppressed by the conservative White forces, with support from Imperial Germany.

The socialist party suffered defeat, but the ideals they championed—universal welfare, education, and healthcare—did not vanish with them.

Instead, those aspirations reemerged in the postwar decades as social democrats built a comprehensive social welfare state that is actually concerned with societal wellbeing, including universal healthcare, free education, and strong social security.

Today, Finland consistently ranks among the happiest countries in the world. It is one case among many that demonstrate how socialist ideals, even despite repression, can reemerge to expand human dignity.

These examples expose the flimsiness of Cold War propaganda, showing that what was long dismissed as “communism,” in practice has translated to improved healthcare, literacy, and security for ordinary people.

Therefore, much of the perceived “failure” to deliver has been preordained by an ideology that views these reforms as a threat to the hegemony of empire, and so has gone to unthinkable lengths to maintain control.

The Unburied Dead and the Need for Historical Reckoning

In retrospect, the victims of America’s war on communism are not faceless abstractions.

They were Guatemalan farmers, Congolese miners, Indonesian student, and Chilean workers. They were civil rights organizers in the United States, freedom fighters in Vietnam, unionists in South Africa, and peasants in El Salvador.

They were poets, teachers, priests, and mothers—ordinary people who dared to demand that the wealth of their nations serve their own communities. For this, they were branded enemies.

Many of their names have been erased. Their bodies lie in mass graves, their movements shattered by coups, their ideas distorted into Western fear mongering and propaganda.

History books in the United States still teach the Cold War as a triumph of democracy over dictatorship. Meanwhile, the Jakarta Method is conveniently absent from classrooms.

COINTELPRO is reduced to a footnote—a diversion from otherwise ethical governance, rather than the domestic blueprint of empire.

These omissions are surgical.

They work to obscure the very possibility of life outside of capitalism.

Subsequently, the lives extinguished, the hopes they had, and the futures they fought to build, are erased.

At the same time, the logic that justified these crimes has not disappeared. The same doctrines—sovereignty as treason, dissent as disorder, violence as peace—are still deployed to defend sanctions, proxy wars, and military occupations.

Cuba remains blockaded. Venezuela remains vilified. Each punished not for tyranny but for daring to gain independence from the empire.

Reckoning with this history requires more than remembrance.

It demands recognition that the fear driving empire has been less examined than inherited.

Politics, like religion, shape the deepest foundations of how people see the world, yet they are the least scrutinized.

Mark Twain observed this phenomenon, stating “people’s beliefs and convictions are in almost every case gotten at second-hand, and without examination, from authorities who have not themselves examined the questions at issue.”

This is how fear becomes tradition, and tradition becomes truth. Whole generations have learned to see empire as defense, and exploitation as freedom.

At its core, it’s the age old Anglo-European arrogance of domination, repackaged in American hands, still cloaked in the empty rhetoric of “liberty” and “democracy.”

These buzzwords are recited as prayers by countless millions tangled in the web of this capitalist cult of extraction.

Until this inheritance is broken, and people begin to unlearn what they have misguidedly been programmed to take as granted, the dead will remain buried in silence, their struggles suppressed behind the gears of capitalism.

In the meantime, the empire will continue its crusade—rebranded, repackaged, but always rooted in the same war against a world that chooses humanity over profit.