September 11, 1973: A Chilean Coup and the Echo of Empire

Decades before the Twin Towers fell, another September 11 marked an American-made tragedy abroad

At dawn on a cool September morning, the town of Santiago, Chile stirred quietly—unaware that within hours, the air would be engulfed by fighter-jets, reigning down bombs on La Moneda Palace.

Just a week before, the city bustled with everyday life: families strolling through Plaza de Armas, schoolchildren heading to class, merchants setting out fresh produce.

Yet, there was also a mood of foreboding just beneath the surface—a tension that had begun to bubble in the weeks prior, as suspicions of a coup began to coalesce.

At La Moneda, the presidential palace, plumes of black smoke billowed from the windows and doors.

Inside, Salvador Allende, the country’s democratically elected Marxist president, stood his ground, his rifle—gifted to him by Fidel Castro—slung over his shoulder, as he delivered his final address over the radio.

Within hours, Allende would be dead, reportedly by his own hand, using the same weapon he’d earlier carried in defiance. Rather than submit to torture and execution, he chose to die on his own terms.

The last photo of President Salvador Allende, in La Moneda’s courtyard on the morning of September 11, 1973.

Soon after, Gen. Augusto Pinochet—propped up by the U.S.—would take power, thus beginning a 17-year dictatorship born not of domestic failure, but of foreign design.

The Chilean coup wasn’t orchestrated on a whim. It was planned methodically and covertly; part of a much larger pattern of intervention that extended across continents and decades.

The September 11 overthrow of Allende remains one of the clearest examples of the violence with which the United States maintains its machinery of empire abroad.

Under this template, American methodologies and monstrosities would be exported again and again, before ultimately returning to their point of origin.

This cyclical inevitability is what post-colonial philosopher Frantz Fanon referred to as the imperial boomerang.

He warned that imperial violence abroad ricochets back to the metropole. Chile’s coup was one such projection of U.S. power, and the echoes linger in how militarized policing, migrant detention, and authoritarian logics manifest inside America today.

Indeed, decades later, that arc would circle back—all upon another unassuming September morning.

The attacks of September 11, 1973 reasserted a well-established doctrine of U.S. interventionism, honed and proliferated across Latin America and throughout the Global South

A Laboratory of Imperial Method

When Salvador Allende won Chile’s 1970 election, he became the first Marxist in the world to come to power through democratic means.

His Popular Unity coalition pursued bold, redistributive reforms: nationalizing copper, expanding public healthcare, implementing agrarian reform.

These were legal policies enacted by an elected government for the benefit of its people.

To Washington, they were insurgent acts; power plays that made Allende even more dangerous.

The Nixon administration feared Chile could become another Cuba. Allende’s socialist policies were framed as an existential threat to U.S. interests, part of a wider Cold War panic about communism

In response, the CIA launched Project FUBELT on the order of President Nixon by way of Henry Kissinger.

"Make the economy scream": President Nixon’s directive for U.S. covert operations in Chile, reflecting a deliberate strategy of economic destabilization to undermine the Allende government.

The operation was two-pronged: first, prevent Allende’s inauguration; second, destabilize his government if prevention failed. Regardless the outcome, Washington was uninterested in coexistence

Nixon himself ordered officials to “make the economy scream” through targeted sabotage and manufactured unrest.

The Hinchey Report revealed that the CIA, under Nixon, financed and orchestrated propaganda operations aimed at undermining Salvador Allende and spreading disinformation through American corporations like ITT as well as media outlets such as El Mercurio.

Economic warfare—cutting off credits, freezing exports, manipulating global prices—created conditions ripe for unrest.

As designed, these strikes and supply shortages were successful in paralyzing Chile’s economy.

After all, this wasn’t the United States’ first rodeo, after all. They’d used similar tactics in Iran (1953), Guatemala (1954), and Jakarta (1965).

Chile was simply the most sophisticated iteration up to that point in time.

When the coup unfolded on September 11, 1973, the United States stood ready with intelligence, logistics, and political cover.

Tactics honed under Project FUBELT would later feed into Operation Condor—a transnational campaign of coordinated repression across South America.

By 1975, Pinochet’s Chile had joined with other right-wing regimes in Argentina, Brazil, Uruguay, Paraguay, and Bolivia to create Operation Condor—a coordinated system of cross-border assassinations, disappearances, and torture.

The U.S. provided technology, training, and intelligence. The rationale was stability. The reality was terror.

| Country | Date of Coup | Condor Role | Repression Tactics | Notable Events |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Paraguay | 1954 | Coordination hub | Interrogation, extradition | Archive of Terror discovery |

| Brazil | 1964 | Trainer & influence | Surveillance, torture | Torture of Rousseff; OBAN |

| Bolivia | 1971 | Peripheral ally | Union crackdowns | Harbored Condor agents |

| Uruguay | 1973 | Early adopter | Mass arrests, torture | Per capita highest political prisoners |

| Chile | 1973 | Founding member | Disappearances, torture, exile | La Moneda bombing; Letelier assassination |

| Argentina | 1976 | Core operator | 30,000 disappeared | ESMA; Mothers of the Plaza |

A nation under fire: Archival footage captures the U.S.-backed military assault on La Moneda Palace, Santiago, Chile — September 11, 1973.

A Coup by Design

The Chilean coup was but one of many expressions of American empire in action—an application of prefabricated plans that were easily replicated from region to region.

In the lead-up to the coup, Washington funneled millions into anti-Allende media campaigns, economic sabotage, and covert political organizing—tactics designed not merely to destabilize, but to fracture the Chilean social contract itself.

These efforts tipped the scales decisively, all but ensuring the collapse of a social democracy that had been legitimately elected just four years earlier.

Once in power, Pinochet’s regime delivered precisely what its foreign enablers had banked on: the swift and violent suppression of democratic ideals.

Backed by Western governments and corporations, the junta moved to dismantle all forms of opposition, with particular ruthlessness directed at any remnants of socialist resistance.

Students, union organizers, clergy, artists, and elected officials were detained, tortured, disappeared.

The state’s apparatus of terror was built for scale. Institutions like the National Intelligence Directorate (DINA) operated with impunity, creating a surveillance state; an open-air panopticon designed not just to extinguish dissent, but to control an entire society.

Facilities like Villa Grimaldi, Londres 38, and the Estadio Nacional became torture centers.

At Colonia Dignidad, a Nazi-founded compound, torture merged with cult abuse in full view of German and Chilean authorities.

Survivors who emerged recalled horrific accounts of electric shock, psychological torment, and mock executions. Many others never emerged at all.

Forensic teams would later uncover mass graves and physical evidence of crimes once dismissed as rumor.

Victim testimony would corroborate a litany of atrocities—from child abuse and medical torture to political assassinations carried out with state complicity.

As the crackdown intensified, more than 200,000 Chileans were forced into exile.

Scattered across Mexico, France, Sweden, Canada, and the United States, they carried with them both trauma and resistance.

For many, exile was not merely displacement—it became a permanent identity, a badge of honor forged in defiance of dictatorship and imperial complicity.

Through underground journalism, music, visual art, oral testimony, and organized protest, Chilean exiles transformed memory into an act of political defiance.

These diasporic movements were instrumental in launching international human rights campaigns that exposed the machinery of Condor when domestic avenues were silenced.

Democracy Without Reckoning

In 1988, a national plebiscite forced the beginning of the end for Pinochet’s rule—at least in a nominal sense.

Though 55 percent of Chileans voted “No” to extending the dictatorship, the transition that followed in 1990 was engineered to protect the regime’s core structures.

Pinochet stepped down as president but remained commander-in-chief of the army until 1998.

Afterward, he was granted a lifetime seat in the Senate, a position crafted by the regime’s own constitution to ensure continued political influence and legal immunity.

Truth commissions would later document the horrific realities experienced under Pinochet.

The Rettig Report (1991) documented over 2,000 deaths and disappearances but avoided naming most perpetrators.

The Valech Commission (2004) went further, identifying over 28,000 victims of torture and political imprisonment—but still offered no judicial consequences.

Ultimately, amnesty laws written by the regime in 1978 shielded most perpetrators from prosecution.

Only through creative legal arguments—such as successfully framing disappearances as ongoing crimes with no statute of limitations—were some cases able to make their way to court.

Even then, accountability remained fragmented, delayed, and partial.

These amnesty laws remained in effect for decades, obstructing trials even as mounting forensic evidence and survivor testimony continued to come to light.

Exporting Empire: The Latin America-to-Middle East Continuum

As the Cold War neared its end, U.S. imperial ambitions showed little sign of slowing. Instead, the protocol was becoming more visible from a global standpoint, as it continued through Latin America and beyond.

Latin America in the 1980s: A Laboratory of Counterinsurgency

In the shadow of Operation Condor, new export pipelines of repression emerged. One of the most notorious: Operation Charly.

Backed by Washington, Argentina's military dictatorship began exporting the same counterinsurgency expertise it had used to terrorize its own citizens.

Argentine officers trained in the School of the Americas at Fort Benning, Georgia helped arm and advise military regimes in Guatemala and El Salvador.

El Salvador became a flashpoint. Over the course of the 1980s, the U.S. funneled more than $1 billion in military aid to its government. The results were catastrophic.

Death squads carried out targeted assassinations. Villages were wiped out. The El Mozote massacre alone left over 800 civilians dead—men, women, and children.

In Grenada, the playbook shifted to direct intervention. In 1983, U.S. forces invaded the island under the guise of rescuing American medical students and curbing a so-called communist threat.

A protest flyer from the early 1980s mobilizing students and community members to demonstrate against U.S. military intervention.

Within days, a leftist government was dismantled, and a Washington-friendly regime was installed.

Middle East in the 1980s–1990s: A Familiar Template

By the late 70s, the U.S. had turned its imperial gaze eastward. The rhetoric changed, but the mechanics remained.

In Afghanistan, 1979’s Operation Cyclone saw the U.S. pour resources into the Mujahideen to bleed the Soviets dry.

Incidentally, it would ultimately be U.S. taxpayers that would do the bleeding.

The operation, which was originally approved for $650,000 would balloon to $700 million a year under Reagan, eventually landing in the neighborhood of $6 billion.

Even more ironically, of those funded, trained, and armed under the program, some would go on to form al-Qaeda.

In Lebanon, U.S. Marines arrived as ostensible peacekeepers in 1982, only to find themselves pawns in a spiraling proxy war.

Their presence coincided with the Sabra and Shatila massacres—where Israeli-backed Phalangist militias slaughtered hundreds of Palestinian refugees.

Meanwhile, the Iran-Contra affair unfolded elsewhere in the shadows—creating a tangled web of arms-for-hostages deals, congressional subversion, and black ops.

Weapons were sold to Iran, a supposed enemy, and the proceeds were secretly funneled to Contra death squads in Nicaragua.

Iraq, too, served as a case study in American interventionism.

In the 1980s, the U.S. covertly supported Saddam Hussein against the very same Iran that it had armed to fund the Contras. Intelligence, weapons, even diplomatic cover were provided. The result was a tumultuous upheaval of life in the region, complete instability rendered by American forces.

By 1991, Hussein was rebranded as a regional menace—the thinly veiled justification for Operation Desert Storm, an action that was more about protecting oil interests than freedom.

What had been lab tested in Latin America became standard policy abroad. From Santiago to Kabul, from San Salvador to Baghdad, the tools of surveillance, coercion, and covert violence traveled easily.

Throughout that decade, the arc of empire grew long, but it bent toward a singular destiny.

The Boomerang’s Return

On September 11, 2001, violence returned to American soil. At 8:46 a.m., the bustling activity of a busy New York City morning came to a halt.

A commercial airliner, commandeered by Al Qaeda operatives, tore into the North Tower of the World Trade Center, killing all aboard and those in the impacted offices.

This initial act signaled the beginning of a different era—one in which the deeply cemented myth of American exceptionalism started to bear cracks.

Just as thousands of New Yorkers were coming out of the concussive daze caused by the blast, they were hit with another wave. At 9:03 a.m., before the dust had a chance to settle, a second plane crashed into the South Tower.

Within the hour, two more planes would target symbols of American power—one military, one political—broadening the scope of the attack from spectacle to strategy.

At 9:37 a.m., a third aircraft struck the western side of the Pentagon, the nerve center of U.S. military power.

At 10:03 a.m., United Airlines Flight 93 was downed in a field near Shanksville, Pennsylvania, in an apparently thwarted attempt at what may have been an attack on the Capitol or the White House.

In total, nearly 3,000 people—most of them civilians with no direct role in their government’s global campaign of violence—were killed in the deadliest attack on American soil since Pearl Harbor.

Reflection Unexamined

For a brief moment, the United States was forced to reckon with an expression of the same violence that so many in the global community had experienced at its hands.

Devastation came from the sky, like so many American made bombs, reigning down on citizens of governments who wouldn’t play ball.

This time it was Americans who emerged from the rubble—joining the ranks of countless others around the world who’d endured the fallout of policy made in Washington.

What might have been a valuable lesson learned was not in fact a reckoning. Instead, it became a pivot.

Within weeks, the U.S. launched its war in Afghanistan. Within months, the invasion of Iraq was underway. This military action—the cost of which currently stand at upwards of $8 trillion—was framed as an act of liberation but operated as extensions of imperial doctrine—toppling regimes, extracting resources, and destabilizing entire regions.

Rather than interrogate the decades of foreign interventions that had sown the seeds of blowback, the American response was to intensify the very logic that had led there in the first place with Shock and Awe campaigns designed to demonstrate military might.

The post-9/11 panic quickly gave way to construction of a sprawling police state—unaccountable, unrelenting, and increasingly barbaric.

In the name of fighting terror, the U.S. government reactivated a familiar toolkit.

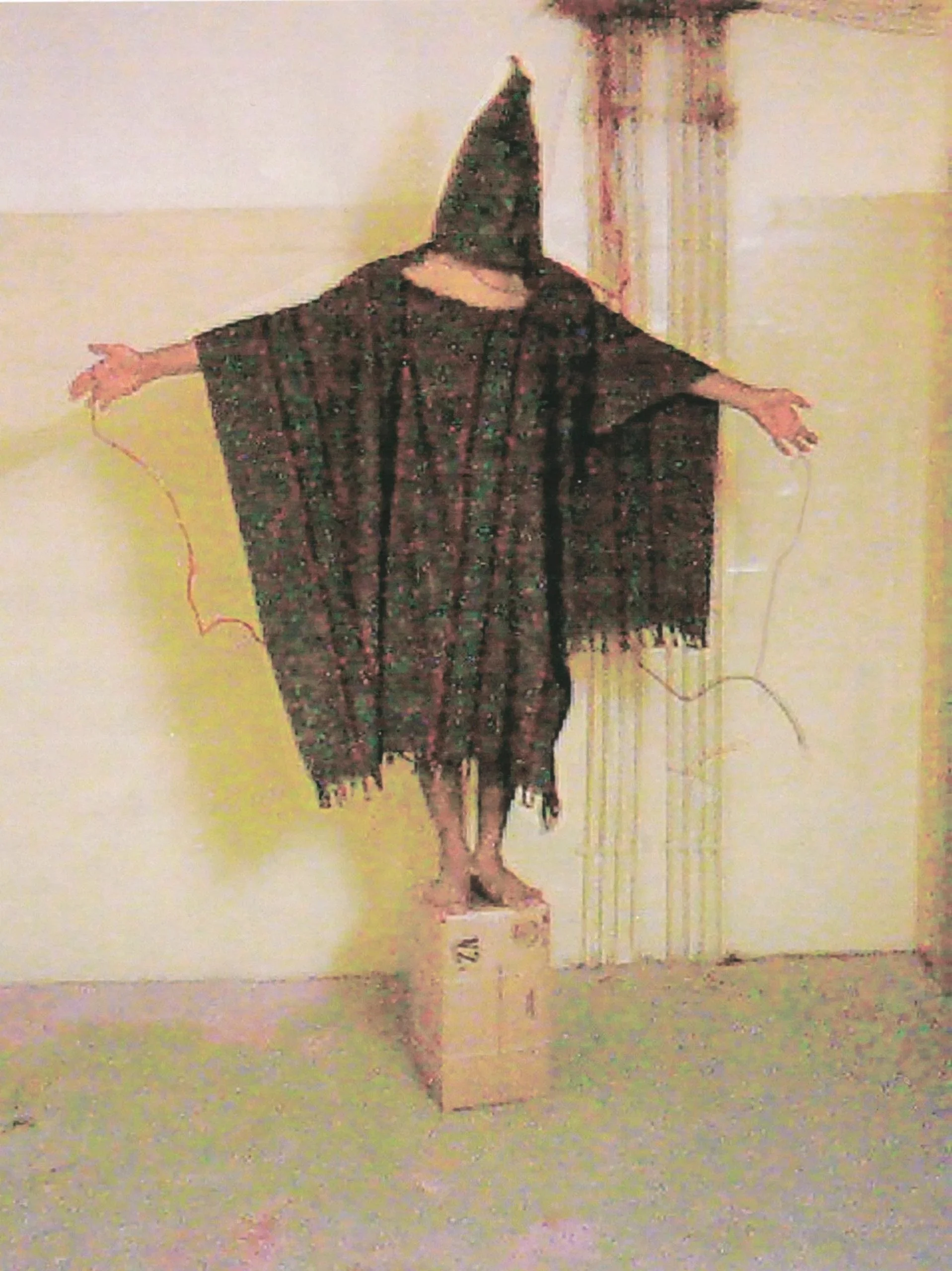

Guantánamo Bay became a “legal black hole” where detainees were held indefinitely without trial.

CIA black sites spanned the globe—secret prisons where torture was sanctioned under euphemisms like “enhanced interrogation.”

Whereas the School of the Americas had once trained Latin American militaries to repress communists, American contractors now trained interrogators to coerce confessions in Bagram and Abu Ghraib.

A hooded detainee stands on a box, arms outstretched, wires dangling from his hands—one of the most infamous images from the Abu Ghraib prison scandal, exposing the brutality and humiliation inflicted by U.S. personnel during the Iraq War.

Surveillance, too, turned inward. The PATRIOT Act and NSA’s warrantless wiretapping programs normalized domestic spying at unprecedented levels.

Tools first honed to monitor “subversives” in Latin America were now aimed at Muslim communities in New York, activists in Oakland, journalists in D.C.

The culture of impunity that marked the Condor years—where torture was justified, accountability was optional, and secrecy was paramount—was reborn in the war on terror.

Figures like Henry Kissinger, never held accountable for enabling extrajudicial killings abroad, were replaced by the likes of John Yoo, Donald Rumsfeld, Dick Cheney.

Even the language echoed Cold War-era : “enemy combatant,” “preemptive strike,” “regime change.”

These buzzwords were uttered on every morning new show, emblazoned across cable news graphics, luring an all new generation into a jingoistic trance.

The boomerang made touchdown—its homecoming denoted not just but fire, but by policy.

What began in places like Santiago and Saigon had circled back, revealing a central truth of empire: what is done abroad will, eventually, be done at home.

Memory Battles and Generational Reckoning

The boomerang may have struck home for Americans, but the imperial currents that still carry it to and fro continue to howl ferociously, thus sustaining the threat of future returns.

In Chile, the bombs have long since stopped falling. What remains is a war over history itself.

Fifty years after the 1973 coup, Chile’s historical memory remains fractured. The torture, the disappearances, the U.S. interference, none of these facts are in dispute.

What is contested is the meaning of those facts, and who gets to define them.

While Chilean elites call for “moving on,” survivors and their descendants have fought to ensure that the dictatorship is remembered not as a tragic chapter, but as a crime with authors.

Among the names that linger loudest is the United States.

The blueprint for authoritarian repression was drafted in Langley, translated in Santiago and throughout the globe.

In the aftermath of the coup, no U.S. president—from Nixon to Trump—has ever issued a formal apology, let alone accepted accountability.

Instead, the U.S. deepened economic ties with Chile through initiatives like free trade agreements and diplomatic overtures—dealings seemingly designed to serve American strategic and commercial interests more than Chilean sovereignty or justice.

Meanwhile, references to the 1973 coup in American high school textbooks, when they appear at all, tend to be brief side notes framed within Cold War narratives.

Ultimately, these lived realities become distanced anecdotes rather than subjects of sustained examination.

Never Forget

Frantz Fanon warned that imperialism “leaves behind germs of rot which we must clinically detect and remove from our land but from our minds as well.”

Sadly, the United States has shown little interest in excising those infectious remnants—neither from its institutions nor from its collective memory, a memory in which it paints itself as a victim of undeserved hostility.

Rather than dismantle the architecture of empire, it has refined it for a new age: leveraging AI tools, updating and sanitizing its language, and shifting the consequences outward, onto others.

There are two September 11s in modern history.

One is seared into the American psyche, memorialized in stone and stadium, invoked to justify everything from surveillance to war. The other is the one the world is made to forget—unless, of course, you are among those who cannot afford to.

In Santiago, it was warplanes, too. It was collapse, too. It was civilians caught in the crosshairs of a project they never consented to.

In the United States, that history rarely rises above a footnote, if acknowledged at all. Whether something becomes a tragedy or a statistic depends entirely on where you're standing when the bombs fall.

It’s all a matter of perspective—unless you’re beneath the rubble.

Sadly, that’s the lesson left unlearned, and consequently, the history we're doomed to repeat

Such is the essence of the boomerang: the arc of imperial violence, launched abroad with confident distance, only to find its way home when least expected.

In Chile, the fight to remember remains ongoing. Memory sites like Londres 38 and the Museo de la Memoria y los Derechos Humanos stand not only as archives of grief but as active battlegrounds over what history means—and who it serves.

In the United States, the refrain “never forget” echoes every September, but it rarely asks what must be remembered, or why. There can be no meaningful memory without interrogation. No lasting peace without accountability.

In the meanwhile, repetition is not inevitable, but it is becoming increasingly plausible.

In recent weeks, the Trump administration ordered the deployment of F-35 fighter jets to Puerto Rico after ordering a military strike on a Venezuelan boat in international waters.

Framed as counternarcotics operations, yet devoid of any due process, these moves mimic the muscle-flexing of Cold War-era containment.

It’s but one of many reminders that the architecture of empire is not only intact, but expanding. Once again, the specter of regime change and chaos looms, cloaked in the rhetoric of national security and regional stability.

The boomerang flies still. Not just toward future collisions, but through our collective capacity to remember what we are so often encouraged to forget.