Alligator Alcatraz: Florida’s Concentration Camp on Indigenous Soil

Florida’s Alligator Alcatraz uses cruelty, legal loopholes, and environmental destruction to turn immigration detention into political theater.

Some see Big Cypress as little more than wetland—a dreary stretch of muck and mire, teeming with some of the most vicious animal life on the continent.

The historical record, however, reveals it to be so much more. For centuries, it has been a sovereign corridor, an ecological artery, and a living archive of resistance.

For the Miccosukee and Seminole peoples, this is sacred ground. It is the connective tissue of their ceremonial, cultural, and familial existence—land they never ceded, land that has survived generations of encroachment.

Now, in the name of “immigration enforcement,” a new campaign has arrived.

Under the camouflage of an “immigration emergency,” Florida has begun converting a long-defunct Cold War era airstrip in Big Cypress National Preserve into a detention complex, dubbed Alligator Alcatraz.

Armed with FEMA funds, executive orders, and little to no oversight, state officials have erected fencing, portable barracks, diesel generators, high-wattage floodlights, and razor wire around the unfinished Everglades Jetport, as the ill-fated jetway was named, all in eight days.

Initially planned near Miami, the Everglades Jetport plans were moved to Big Cypress, sparing Florida’s metropolitan residents noise pollution, passing that burden onto tribal peoples instead.

Environmental pushback halted the project after just one runway, which subsequently stood abandoned for decades. Now, its isolation has become its appeal—a detention site in a new era of state-sanctioned disposability.

If what has emerged from this stolen terrain seems eerily familiar, it’s because we’ve been here before.

From America’s first concentration camp at Fort Snelling in 1862 to those camps that confined Japanese Americans during World War II, each holds its own dubious place in American history.

They’re always marketed as temporary, these desperate measures born of frenzy, justified by national security. Regardless, the damage left behind is permanent.

Each instance of subjugation stands as part of a lineage the American public is reluctant to name.

Alligator Alcatraz is just the latest iteration in a familiar routine: declare a crisis, suspend oversight, target a vulnerable population, and operate out of the view of the public.

Desert camps, offshore barges, or now a remote Everglades preserve, the goal is the same: isolate, punish, and disappear.

The Long Arc of Immigration Detention

Since the earliest enforcement of its dubiously acquired borders, the U.S. has treated immigration as a tool of social engineering, racial sorting, and class enforcement.

In two-and-a-half centuries, the mechanisms may have evolved in scope, intensity, and bureaucracy, but the goal has remained the same: control the entry of marginalized populations under the guise of national security.

Immigration policy has expanded whenever the country needed cheap, expendable labor—only to criminalize, ostracize, or otherwise discard those who answered the call.

Upon arrival, each group became both indispensable and disposable—a pattern that repeats, era after era, under new justifications but the same guiding logic.

Chinese laborers built the transcontinental railroad, yet were still met with violence, exclusion, and the very first American immigration ban based solely on ethnicity.

Similarly, Jewish, Italian, and Irish immigrants arrived in droves, driven by pogroms, poverty and persecution, only to be funneled into unsafe jobs, tenement slums, and second-class citizenship.

Immigration by the numbers

Jewish immigrants: Over 1.5 million primarily Eastern European Jews immigrated to the U.S. between 1881 and 1914, fleeing pogroms in throughout Russian empire and beyond.

Italian immigrants: Roughly 4 million Italians arrived between 1880 and 1920, most from southern Italy, escaping agrarian poverty and political upheaval.

Irish immigrants: Nearly 2 million Irish came between 1845 and 1855 alone due to the Great Famine, with estimates totaling 4.5 million by the end of the 19th century.

By the mid-19th century, immigration policy had taken on a physical shape.

Castle Garden, built in 1855 at the edge of Manhattan, served as both military fort and immigration checkpoint.

Eventually, the facility proved incapable of managing the sheer volume of arrivals, and federal authorities began building a larger processing station offshore.

In 1892, Ellis Island, a much bigger, more bureaucratic operation, replaced it as the nation’s primary immigration station.

Its opening marked a deeper, fully-federalized authority over entry into the land, taken by force, now controlled by the descendants of those who, themselves, displaced its original habitants.

The shift toward detention as a punitive tool came gradually, then seemingly all at once.

In the 1980s, the Reagan administration began detaining Haitian and Cuban asylum seekers—some for years—marking the first widespread use of incarceration for migration control.

Reagan’s policies also opened the door to private prison corporations, granting early detention contracts to companies like Corrections Corporation of America, now CoreCivic.

The 1990s saw bipartisan acceleration.

The Clinton administration passed the 1996 Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act (IIRIRA), which expanded the scope of mandatory detention and authorized the removal of lawful residents for minor infractions.

Suddenly, longtime community members—some with children, mortgages, even military service—were subject to imprisonment and deportation over offenses as minor as traffic tickets or expired documentation.

The events of September 11, 2001, marked an even more drastic turning point.

With the subsequent passing of Patriot Act in their aftermath, immigration enforcement expanded powers under a banner of national security, reshaping priorities and loosening legal constraints.

After the passage of the Homeland Security Act the following year, the federal government consolidated immigration enforcement under the newly created Department of Homeland Security (DHS).

Out of that reorganization came the Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE)—a new agency built specifically to carry out deportations, surveillance, interdictions, and prolonged detention.

Once immigration was successfully reframed as a national security issue, detention became the predictable next step.

By 2019, ICE was holding over 50,000 people per day—many of them asylum seekers, lawful residents caught in status disputes, and families fleeing violence.

The expansion was driven not just by policy, but by profit. Private prison operators like GEO Group and CoreCivic signed contracts worth hundreds of millions to construct and manage detention centers across the country.

This expansion came with increasing legally ambiguous enforcement tools—tactics that bypass traditional judicial oversight and operate with sweeping discretionary power.

Emergency Powers as the New Prototype

In January 2023, Governor Ron DeSantis declared an “immigration emergency,” citing what his administration called federal negligence at the southern border.

This, despite the fact that the Biden Administration had, at that point, already surpassed the preceding Trump presidency in numbers of deportations.

Nevertheless, with the stroke of a pen, DeSantis’ executive order afforded his administration broad latitude to act without public input or procedural review.

Under this sweeping authority, the state seized the Dade-Collier Training and Transition Airport (formerly Everglades Jetport)—wedged deep inside Big Cypress National Preserve—and began converting it into the immigration jail.

Miami-Dade County, which owns the parcel, was never consulted. Neither were the Miccosukee, whose sovereign claims span the surrounding wetlands.

Within eight days, the site was transformed. Private contractors—coordinated through the Florida Division of Emergency Management—erected aluminum-frame barracks, floodlights, fencing, and diesel-powered infrastructure.

Trucks owned by private contractors with their company names conspicuously obscured, almost as if participating in legally and ethically dubious activity.

By declaring a crisis, bypassing regulation, and building beyond public view, the state had mapped out a template—one that relies on procedural shortcuts and jurisdictional gray zones to fast-track incarceration.

That strategy soon went national.

In July 2025, the Department of Homeland Security and FEMA unveiled a $608 million Detention Support Grant Program, inviting states to seek funding to build or expand migrant detention infrastructure.

Florida applied immediately, seeking to recoup the estimated $450 million annual cost of its swamp-based facility.

Homeland Security Secretary Kristi Noem hailed Alligator Alcatraz as a blueprint for future detention operations, cementing a unilateral state maneuver into federally sanctioned precedent.

With FEMA dollars in play, the regulatory void surrounding Alligator Alcatraz has apparently become the template for national immigration enforcement.

Pipelines Beyond the Swamp

Florida’s foray into immigration detention didn’t begin with Alligator Alcatraz.

Before construction broke ground in Big Cypress, the state was already participating in deportation pipelines that funneled detainees directly into El Salvador’s Terrorism Confinement Center—better known as CECOT.

Heralded by Salvadoran President Nayib Bukele as a model of order, CECOT has drawn international condemnation for mass internment, indefinite detention, and systemic human rights abuse.

U.S. partnership with the prison deepened under Donald Trump, who praised Bukele’s iron-fisted approach as “the future of public safety” and pursued it as a model to emulate.

Florida has seemingly taken that cue.

From mass incarceration without trial to the strategic invocation of state emergencies, the state mirrors the same legal contortions Bukele used to justify CECOT—suspending constitutional protections under the guise of crisis response.

That this model is imported from El Salvador is certainly noteworthy. It reactivates a long and fraught relationship with a country whose internal crises have, in no small part, been shaped by U.S. interference.

For decades, the United States funded and directed covert operations, death squads, and civil war–era repression inside Salvadoran borders.

The subsequent conditions not only drove mass migration but also fueled the cartel and gangland violence born from the power vacuums they left behind.

Unlike those Cold War–era interventions, however, this arrangement unfolds in broad daylight—an indication of how times have changed.

No more secret cables. No deniable operatives.

Just a $6 million agreement and a public endorsement of a regime that cages thousands without trial, which has been touted by Trump as policy innovation.

That innovation took physical form—first at CECOT, to be sure, but the same disregard for due process and human rights was also implemented, albeit on a smaller scale, at Alligator Alcatraz.

For all intents and purposes, it’s the domestic counterpart to the Salvadoran prison colony: a facsimile built on the same foundation.

The two facilities are linked by a shared logic—one that prioritizes speed over scrutiny, erases accountability, and treats people as logistical burdens rather than human beings.

Sites like Alligator Alcatraz function as modular nodes in an expanding enforcement economy, where public money feeds private contractors, legal safeguards are deliberately bypassed, and emergency declarations serve as the scaffold for indefinite incarceration.

In this system, geography becomes camouflage, and the border becomes wherever the state decides to draw it next.

Precedents in U.S. Confinement

Guantánamo Bay (Cuban Rafters Crisis, 1994)

A makeshift encampment built on a U.S. naval base to contain over 30,000 Cuban refugees who fled by sea.Following the 1994 balseros crisis, the Clinton administration ordered that Cuban migrants intercepted at sea be diverted to Guantánamo Bay rather than processed on U.S. soil. Conditions were austere and prison-like: barbed wire, outdoor barracks, limited medical care, and indefinite confinement. Many remained in legal limbo for over a year, with no access to asylum hearings.

Guantánamo Bay (Haitian Refugees, 1991–1994)

A segregated camp system designed to detain Haitian refugees fleeing political violence in the wake of Jean-Bertrand Aristide’s ouster.Unlike Cubans, Haitians were routinely denied entry or asylum consideration. Many were confined in makeshift tents with minimal medical care. Some were held in a separate HIV-positive camp, prompting a legal battle (Haitian Centers Council v. Sale) that exposed discriminatory treatment and ultimately upheld the government’s authority to interdict and detain offshore.

Krome Detention Center (Miami, 1980s–1990s)

A former missile base turned immigration processing and detention center, primarily housing Haitian and Cuban migrants.The facility gained notoriety for overcrowding, poor sanitation, and human rights violations. Though not fully outdoors, detainees were often held in military-style tents on-site or in temporary structures meant to process surges in arrivals. The ACLU and Amnesty International condemned conditions throughout the 1980s and 1990s.

Camp Bulkeley (Guantánamo Bay HIV Unit, 1991–1993)

A walled-off portion of the Guantánamo refugee camp where HIV-positive Haitian refugees were forcibly detained.In what became one of the most infamous U.S. public health carceral decisions, the Bush and Clinton administrations confined over 200 Haitian refugees with HIV under the justification of protecting U.S. public health. The camp was eventually shut down after sustained legal and activist pressure, and many detainees were resettled in the U.S.

Facility Conditions and Human Rights Concerns

Inside Alligator Alcatraz, accounts paint a grim picture.

Lawyers and detainees report that basic hygiene and medical care are sorely lacking.

One detainee told the Associated Press, “The conditions in which we are living are inhuman… My main concern is the psychological pressure they are putting on people to sign their self-deportation.”

He described “zoo cage” tents with eight bunk beds each, closed off with metal fencing, swarming with mosquitoes, crickets and frogs, where people are kept locked around the clock.

One Cuban detainee echoed this description, calling the facility a “dog cage,” with his countryman revealing “I feel like my life is in danger.”

Others say trays of food are served once per day and “the meals have worms,” while toilets often overflow onto the floor. Still others report detainees have “no way to bathe, no way to wash…” and that the toilets were “flooded with pee and poop.”

Religious and cultural needs have also reportedly been ignored. In one case a detainee said guards confiscated his Bible and told him his “right to religion” didn’t apply at Alligator Alcatraz.

Observers note that detainees have minimal privacy or sleep: lights are left on 24/7, and guards cuff prisoners whenever they are moved or brought for processing.

Toilets doubling as sinks and cramped bedding reveal a lack of privacy

Lawyers argue that these conditions rise to the level of cruel and unusual punishment, in violation of the Constitution. Of course, that’s to say nothing of the internationally recognized rights enshrined in the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR).

Detainees report being forced to strip in front of others, a direct breach of ICE’s own detention protocols.

Standards that mandate privacy, clean bedding, fresh water, and medical care appear to have been disregarded entirely.

Health and safety are pressing concerns.

Florida’s summer heat and the camp’s flimsy construction create serious risks of heat stress. Mosquito-borne diseases and other tropical illnesses are endemic in the swamp.

About a week into the processing of detainees into the facility, reports of such afflictions had already started making news.

Still, detainees report only basic first aid, with even medicine often unavailable.

Attorney Katie Blankenship relayed that detainees go days without showers and lack even soap or toothbrushes, these harsh conditions are highly traumatic.

More than one outlet has dubbed the camp “Alligator Auschwitz,” and historians like Andrea Pitzer (author of Concentration Camp) argue that Alligator Alcatraz fits an objective definition of a concentration camp – mass civilian detention of a targeted group, without trial, for political purposes.

As has been noted, many held at Alligator Alcatraz have no criminal records or past convictions. Blankenship’s client, for instance, was a 15-year-old was reportedly detained simply for a minor traffic offense.

Detaining them under such conditions raises serious questions of due process and human rights.

Even tracking detainees proves unreliable.

A recent ‘technical error,’ according to DHS, caused thousands of individuals to vanish from ICE’s online locator—rendering their whereabouts unknown to families, attorneys, and advocates at the height of national scrutiny.

The state’s response has been to downplay or deny.

Florida’s emergency management spokeswoman declared these reports “complete fabrications,” insisting in a press release that “every detainee has access to medicine and medical care” and receives three meals, water and showers as needed.

The governor himself has repeatedly claimed the facility is only temporary and will have “zero environmental impact.” These assurances ring hollow to critics.

Immigration advocates and watchdogs stress that a detention policy “built in secret” with no independent monitors is inherently abusive.

Lawyers like Atara Eig argue that neighboring detention centers start to look good by comparison; she said Alligator Alcatraz’s conditions make other ICE facilities seem “advanced” by comparison.

Ecocide as Statecraft

The decision to build within one of the nation’s most biodiverse wetlands reflects more than mere logistics. It signals a calculated confidence that emergency powers will supersede federal environmental protections.

Federal authorities have flirted with catastrophe here before. When the massive commercial jetport was first proposed in the late 1960s, the nation's top conservation scientists warned it would irreparably destroy the entire south Florida ecosystem.

Even Marjory Stoneman Douglas, whose activism helped birth the modern Everglades conservation movement, stood among those who sounded the alarm.

Ultimately, the project was defeated—but only through fierce resistance.

Today, the same swamp once ruled too precious to bulldoze is back in the crosshairs of that same ecological brinkmanship—this time at a far less opportune moment in climate history.

Florida’s Big Cypress site, like so many other carceral outposts disguised as shelters, transforms ecological sanctuaries into zones of exception.

Species protections stall, tribal sovereignty is skirted, and floodplain construction somehow gets fast-tracked under the pretext of “public safety.”

The swamp becomes silent witness to a new kind of warfare: one waged not only on the environment, but on the people trapped within it.

With the same exported disregard for ecological destruction with which the U.S. has fueled the global climate crisis, the jetport now becomes the latest landing strip for the environmental boomerang—its consequences returning to plow over those the state has imprisoned.

Even the quietest inhabitants—pythons, alligators, endangered species whose survival already hangs by a thread—aren’t spared from the fallout.

Their displacement and the broader ecological toll have become the focus of mounting litigation.

In the Sonoran Desert, an similar scenario may soon be taking shape—this time instead of pythons and sea turtles, it’ll be rattlesnakes and desert tortoises bearing silent witness.

Arizona Alcatraz? Marana Facility May Be Next Zone of Exception

In July 2025, the state of Arizona quietly sold the defunct Marana Community Correctional Treatment Facility—a 500‑bed private prison in Pima County—to Management & Training Corporation (MTC) for $15 million, with no restrictions on its future use.

The timing of the sale—just days after the passage of Trump’s $45 billion “One Big Beautiful Bill” for immigration detention—has raised questions about whether the facility is poised to join a new wave of federally subsidized incarceration sites.

Earlier in the year, state Sen. John Kavanagh introduced a nearly identical bill that would have leased the prison to ICE for just $1 per year—but it failed in the House.

Now, with MTC back in control and federal dollars flowing, the facility may be repurposed under the same discretionary framework that enabled Florida’s Alligator Alcatraz.

The setup mirrors Florida’s trajectory—an unused area purchased by an ICE contractor, poised to become a detention hub behind an opaque legal and bureaucratic curtain.

If confirmed, Marana would reaffirm Arizona’s enduring role as a cornerstone of it.

From SB 1070 to sprawling border enforcement infrastructure, Arizona has long served as a laboratory for carceral immigration policy

Legal Challenges & the Precedent at Stake

In late June 2025, Friends of the Everglades, the Center for Biological Diversity, and the Miccosukee Tribe of Indians filed suit in federal court.

Their case challenges both the construction and operation of the detention site on multiple legal grounds—including violations of the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), the Endangered Species Act (ESA), and failures in tribal consultation procedures.

The lawsuit is centered on a deceptively simple maneuver: Florida designated the site as a “shelter and services” facility rather than a detention center, enabling it to bypass procedure while still unlocking FEMA emergency dollars.

This “shelter” designation notwithstanding, the site undeniably bears all the characteristics of a carceral compound—military fencing, searchlights, intake procedures, surveillance towers, and mass confinement under armed guard.

With endangered wildlife at risk, sovereign tribal rights ignored, and the Constitution’s foundational protections placed on hold, the legal implications extend far beyond state lines.

Behind the statutes, behind the bureaucratic sleight-of-hand, are people—held under constant light, in close quarters, with no privacy to be found.

Families divided by fencing. Children funneled through intake like inmates. Entire communities living in fear of disappearing into a rogue system with no oversight and no exit.

This is more than a fight for ecological, tribal, and human rights—it’s a fight for the moral conscience of the nation.

It’s everyone’s fight, and it doesn’t end in the courtroom.

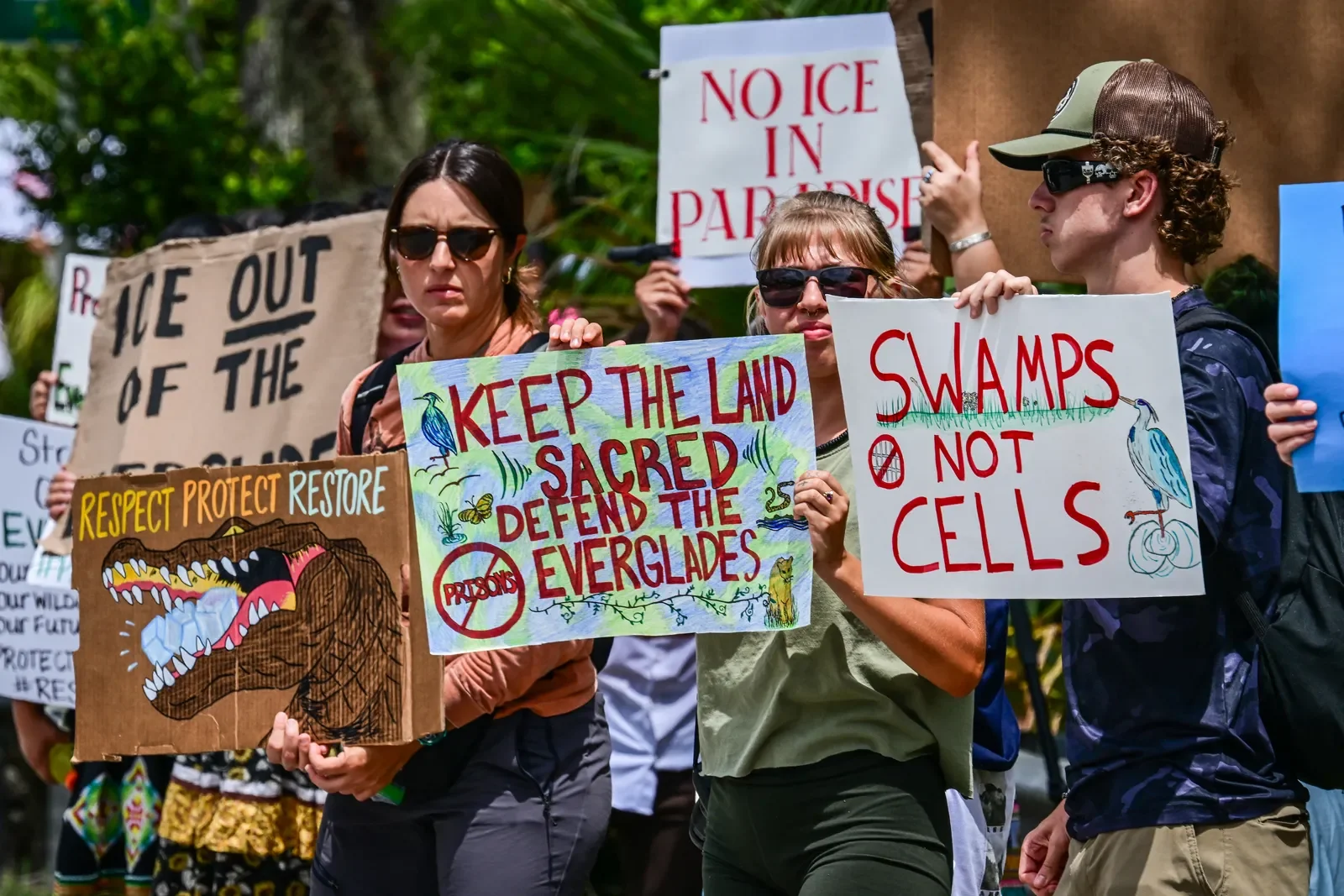

Along the Tamiami Trail—the only paved outlet connecting the compound to the outside world—protesters have already mobilized.

Their presence signals what courts have so far failed to acknowledge: more than just a site of detention, this swampland is a battleground for personal liberty itself.

They stretch across ideological patchworks and sovereign lands—along the contours of a nation reshaped by carceral logic—where the pretext of crisis displaces the rule of law, and containment the default response.

Indeed, Alligator Alcatraz is an apparatus of a much larger system—a police state that normalizes indefinite detention, short-circuits due process, and treats procedural safeguards as expendable under the vague cloak of “emergency response.”

It’s all part of that replicable model, the one that converges environmental degradation, racialized enforcement, and democratic backsliding into a single operational template.

It echoes the blueprint of domestic militarization—from urban training sites like Cop City to borderlands designed for containment rather than compassion.

What’s happening in the swamp isn’t just a local scandal. It’s a glimpse of the road ahead—unless we draw the line, here, in Big Cypress.

The Border Is a Lie

Freedom of movement should not depend on ink and rubber stamps—least of all from a nation whose origins include the theft of the very land they now regulate.

It’s pointless to further debate about whether Alligator Alcatraz is too harsh or too remote or too politically divisive. It’s enough that this debate can even be waged as the detained languish under a total restriction of movement.

We need to call it what it is: the material expression of supremacist worldview, weaponized to erase the people it deems disposable. A literal concentration camp, built by real-life fascists.

Unless that worldview is dismantled, this “camp-as-crisis” model will replicate state by state. It’s already happening.

Governing bodies and private contractors alike are champing at the bit to build more remote compounds, enshrine new exceptions to due process, and normalize the idea that proximity to a border voids your rights.

All of this, with taxpayer money, at a time when the average taxpayer is already leveraged to the hilt.

It wasn’t always this bleak. History reveals that immigration wasn’t always viewed through a punitive or carceral lens. It was once far easier for people to move and travel as they wished.

Until the early 20th century, passports weren’t required for most international travel. Movement was largely unrestricted.

That changed after World War I, when surveillance states emerged from the wreckage of empire. The League of Nations made the modern passport standard in 1920.

A simple paper booklet became the hinge between freedom and exclusion.

Today, we treat it as a prerequisite for dignity—rarely so much as acknowledging the privilege that makes that dignity possible.

Where once people moved freely, we now move only with permission—granted or denied based on invisible borders drawn by conquest and formalized through paperwork.

Noam Chomsky once described this era of the modern passport regime as one of history’s greatest tools of state repression, noting that national borders exist not to facilitate security, but to enforce hierarchy.

Even Golden Age legend Charlie Chaplin, exiled under McCarthyism, loathed the very notion of a passport as a tool of state control.

He made that critique explicit in a monologue written for his son in A King in New York (1957), warning of its threat to freedom and independent thought:

“They have every man in a strait-jacket and without a passport he can’t move a toe... If you don’t think as they think, you’re deprived of your passport... We’re turning into a country of intellectual eunuchs!”

— Michael Chaplin as Rupert Macabee

What Alligator Alcatraz reveals, in its sterile cruelty, is that caging humans is not the exception, it’s the system manifest.

The criminalization of migration and the erosion of movement rights reflect the architecture of a police state—one in which the logic of control and containment bleeds into every facet of life.

Emergency is no longer a temporary condition. It is the standing justification. Just like the passport, it becomes a paper-thin veil through which freedom is revoked.

There is no humane way to cage, neither is there an ethical manner in which deprivation is enforced, nor is there any reforming what is fundamentally punitive and supremacist.

Once this conclusion is reached, all that remains is decriminalization—dismantling the border as an instrument of state violence, and reclaiming movement as a basic human right.

All that’s left to do now is dismantling, line by line, facility by facility, doctrine by doctrine, the system that made this possible.

The future will be borderless. The movement to make it so has already begun. Refusal of this reality amounts only to a sad, futile display of hubris.