The Cuba Embargo: A Relic of America’s Six-Decade Grudge

The Cuba embargo hasn’t toppled Havana, but it has exposed U.S. hypocrisy while highlighting how shared resources and collective resilience outlast empire.

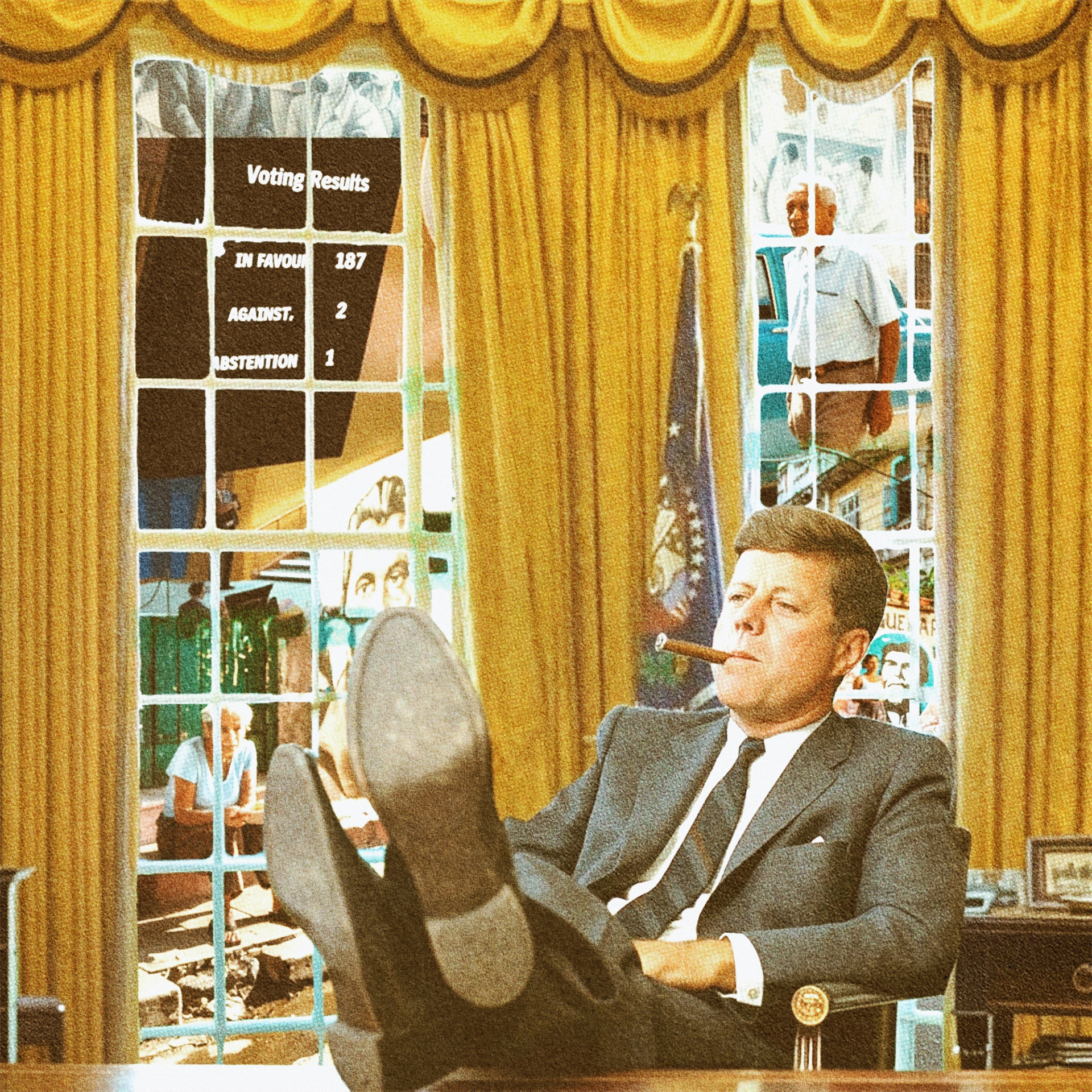

For the 32nd year in a row, the United Nations General Assembly has voted overwhelmingly to condemn the U.S. economic embargo on Cuba, which recently entered its 63rd year.

The annual rebuke—supported by 187 of the world’s 193 nations—has become a fixture of international diplomacy, running for more than half the life of the embargo itself.

In the most recent vote, only two nations voted against lifting the embargo: the United States and Israel.

At this point it’s apparent: America’s longest-running sanctions game endures not because of effectiveness, but because it satisfies the political impulse to punish defiance, even as the rest of the world demands an end to this futile, petty display of bitterness.

For a brief moment in the mid-2010s, it seemed like that might change.

In December 2014, President Barack Obama acknowledged, “We can never erase the history between us.” It was a rare public nod to the deep scars of America’s relationship with the island.

For the first time in a half-century, the United States was moving to normalize relations with Cuba.

In 2016, Obama became the first U.S. president to visit Cuba in nearly ninety years, declaring in Havana that he had “come here to bury the last remnant of the Cold War in the Americas.”

Travel and trade restrictions were eased, bi-lateral agreements reached, and both nations spoke cautiously of a future built on engagement rather than isolation.

This moment of candor, in all its pomp, still grossly understated the breadth of that history: military invasions, assassination plots, economic strangulation, and state-sponsored terror waged across more than a century.

Washington’s economic embargo—a blockade designed to suffocate Cuban society—is often presented as a Cold War holdover, a misguided tactic to pressure Havana into “democratic” reforms.

In reality, it is just one instrument in a much broader campaign of hostility that began the moment Cuba freed itself from Spanish colonialism.

From the outset of the 20th century to the present day, Cuba’s insistence on genuine independence has been met with American imperialism dressed in a lexicon of “freedom” and “human rights.”

While proclaiming itself a champion of liberty, the United States has long inflicted deprivation and terror on a small island nation whose greatest offense was asserting the right of self-determination in defiance of Washington’s dictates.

Coveting Cuba: American Expansionism and the “Infernal Little Republic”

The roots of U.S. aggression toward Cuba reach far deeper than the Cold War.

Long before Fidel Castro or Soviet alliances, the island’s location, resources, and strategic potential made it a coveted prize for American expansionists.

For 19th-century U.S. policymakers, a fully independent Cuba was simply not a part of the plan. Instead, as historian Louis Pérez reveals, Cuban sovereignty had been “anathema to all North American policymakers since Thomas Jefferson.”

By the time Cuban revolutionaries mounted their final push to overthrow Spanish rule in the 1890s, Washington’s designs on the island were already well established.

Once it became evident that Cuban revolutionaries would defeat Spain, the United States swooped in—presenting itself as Cuba’s ostensible savior, but all the while carving out for itself whatever it desired.

The resulting 1898 Spanish–American War, celebrated in U.S. textbooks as a noble rescue from tyranny, was in reality the hijacking of another nation’s revolution.

As Pérez puts it, “A Cuban war of liberation was transformed into a U.S. war of conquest.”

Cuban fighters, who had sacrificed for decades to expel Spain, were barred from marching into Havana to celebrate their victory.

Instead, they watched as their independence—finally within view—was stripped away, right at the moment it should have been secured, replaced instead by a new occupier draped in the language of liberation.

Theodore Roosevelt’s sneering reference to “that infernal little Cuban republic” aptly captured the imperial mindset: Cuba’s role was to be a grateful subordinate, not a sovereign equal.

That year’s “Uncle Sam’s Picnic” political cartoon, depicting the U.S. cheerfully loading Cuba, Puerto Rico, the Philippines, and Hawai‘i into a wagon of conquered territories, made the message unmistakable — America had joined the ranks of overseas empires, and Cuba was expected to ride along.

Old Party: “Ain't ye takin' too many in, Sam?” Uncle Sam: “No, Gran'pa; I reckon this team will be strong enough for them all!'“

- Dalrymple, 1898. Illus. from Puck, v. 44, no. 1125

Any remaining illusion of Cuban freedom dissolved with the Platt Amendment of 1901, which the U.S. forced into Cuba’s constitution as a condition for ending its military occupation.

The amendment gave Washington the unilateral right to intervene in Cuban affairs and granted it perpetual control over naval bases, including Guantánamo Bay — which is still held against Cuba’s will today.

Early 20th-century U.S. policy treated Cuban governments as provisional administrators, to be replaced or propped up according to American interests.

By mid-century, the arrangement had solidified into a full-blown neocolonial order. U.S. corporations owned most of Cuba’s utilities, half its sugar industry, and large portions of its railroads, banks, and oil refineries.

Put simply, Cuba’s economy was effectively owned, part and parcel, by the United States.

Washington justified this control under the banner of “protecting Cuban independence” from foreign influence, all while ensuring that true independence never took root.

This pattern — appropriating the language of liberation to justify conquest — would define every subsequent phase of U.S.–Cuban relations.

From Dictatorship to Revolution

By the mid-20th century, Cuba was “independent” only in a nominal sense, while being firmly positioned under Washington’s thumb in a far more actual sense.

The most blatant embodiment of this arrangement materialized in the form of Fulgencio Batista — a military strongman who rose to power with U.S. support and ruled, on and off, from 1933 to 1959.

His second stint in office, attained through a 1952 U.S.-backed coup, cemented his status as a compliant proxy for American business interests.

U.S. Under-Secretary of State Sumner Welles with Cuban leader Fulgencio Batista as General Malin Craig,American Army Chief of Staff, looks on, 1938.” Universal Images Group.

Under Batista, Havana was marketed as a playground for U.S. tourists, investors, and organized crime.

Mob-connected casino operators and hotel magnates carved out turf, while U.S. corporations gained control of Cuba’s most profitable industries.

Batista’s government protected these arrangements at all costs, deploying state violence to crush dissent and keep foreign capital secure.

Political opposition was met with imprisonment, torture, or death.

Nevertheless, the brutality of Batista’s regime rarely figured into the American narrative of Cuba’s so-called “pre-Castro prosperity” era.

Washington’s relationship with the dictator was one of convenient amnesia — so long as profits continued flowing, repression was an internal matter.

That selective memory remains visible today, sometimes in the unlikeliest of places.

Ted Cruz perfectly encapsulates the historical inversion in U.S. political rhetoric. The torture is acknowledged, but its perpetrator, a U.S.-backed dictator, is an afterthought if not forgotten completely in favor of a cleaner Cold War morality tale.

By the early 1950s, resistance to Batista’s regime was growing. Corruption was rampant, inequality stark, and the promise of independence vanished into thin air.

The opposition began to coalesce around Fidel Castro, whose call for armed struggle against repression resonated with a population exhausted by decades of foreign interference and domestic repression.

It came to be known as the 26th of July Movement, named for Castro’s failed 1953 assault on the Moncada Barracks.

The assault on the barracks was meant to capture its arsenal—the weapons would arm rebels in a broader campaign to overthrow Batista.

Instead, the botched mission left dozens dead and sent Fidel and his brother Raúl to prison, where Fidel delivered his famous History will absolve me speech

After a general political amnesty was declared in 1955 — a move intended to defuse dissent and polish Batista’s tarnished image — Castro was released from prison and went into exile in Mexico.

This attempt at positive PR would prove disastrous for the dictator and his regime.

Once in Mexico, Castro reunited with other Moncada survivors, joined forces with Camilo Cienfuegos, and forged a pivotal alliance with Ernesto “Che” Guevara.

In December of 1956, Castro and 81 rebels launched their return to Cuba aboard the yacht Granma.

The return to Cuba embodied the improvised, almost quixotic character of Castro’s movement. The vessel chosen for the invasion was Granma — a small, aging 60-foot cabin cruiser.

Designed to hold a dozen passengers at most, it had long since passed its prime when it was quietly purchased in Mexico for $50,000, money scraped together from exile supporters.

The landing was ill-fated: most were killed or captured, but a small band — including Castro, Guevara, and Cienfuegos — managed to escape into the Sierra Maestra mountains.

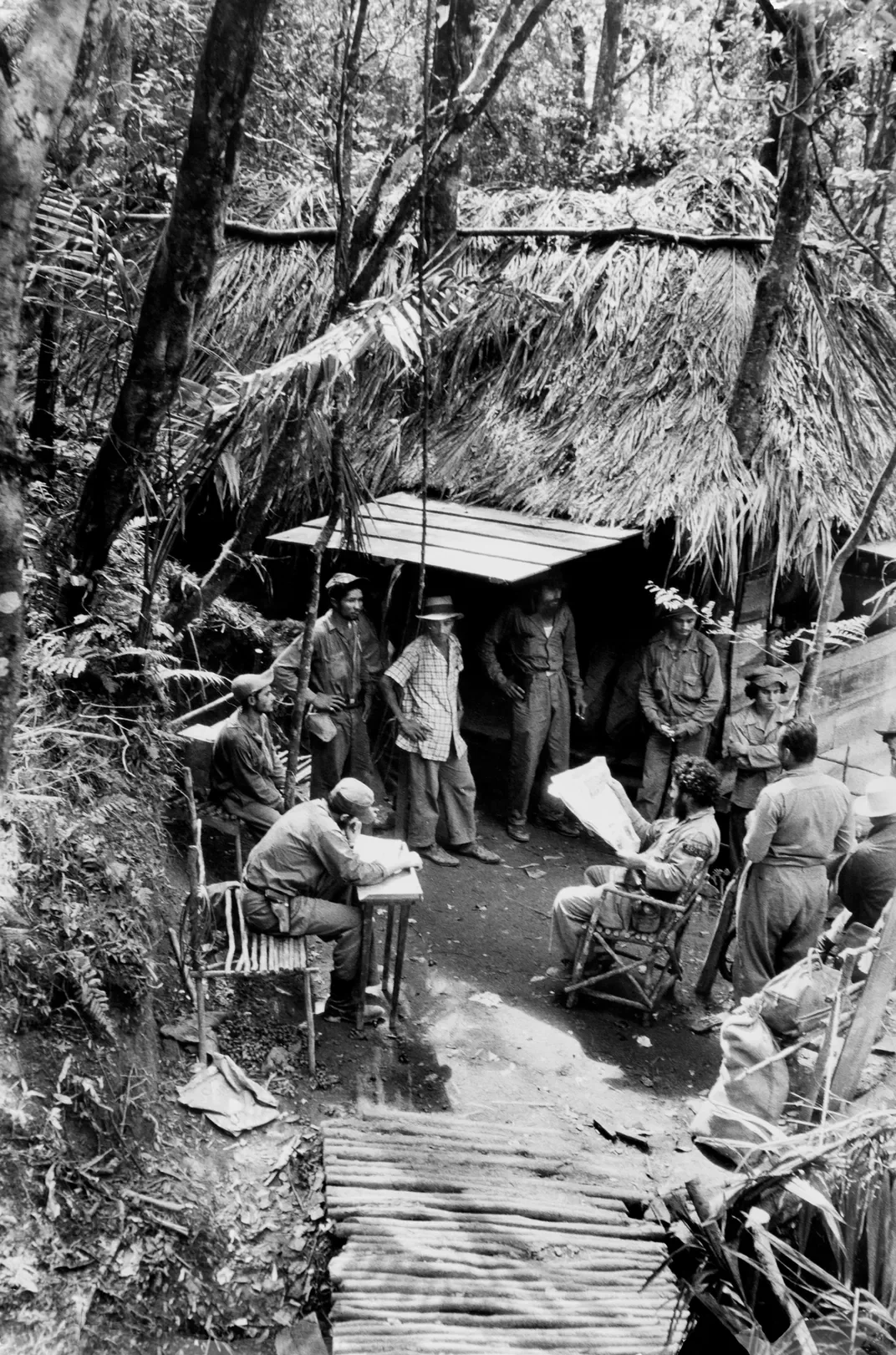

There, they built a guerrilla insurgency that drew strength from peasant support, student movements, and disaffected sectors of Cuban society.

Fidel Castro and fellow revolutionaries in their Sierra Maestra encampment, 1958 — plotting strategy in the rugged mountains that became the cradle of Cuba’s liberation movement.

Despite being outnumbered and outgunned, the rebels leveraged Batista’s crumbling legitimacy and a demoralization of his Army, to turn the tide. By late 1958, the regime was collapsing under the weight of its own corruption.

On New Year’s Day, 1959, Batista fled into exile.

Whereas the Cuban rebels who’d once ousted the Spanish had been barred by U.S. forces from entering Havana to celebrate, the revolutionaries who toppled Batista marched triumphantly into the capital unopposed, greeted as victors.

For many Cubans, it was the first time in living memory that the island’s political destiny seemed truly in Cuban hands.

A sea of supporters fills Havana’s Plaza de la Revolución in 1959, rallying behind Fidel Castro amidst promises of agrarian reform, sovereignty, and social justice in the wake of Batista’s fall.

Unlike the hollow pretenses of liberty or democracy invoked by Batista and his puppeteers, this was not rhetoric but reality — a material departure from the old order.

Under the new government, sovereignty was asserted not in slogans and soundbites, but though tangible, measurable change.

One of the first acts the new leadership took was to nationalize foreign-owned assets — including billions of dollars’ worth of U.S. properties.

New land reform laws broke up vast estates, redistributing farmland to the peasant class.

Healthcare and education became universal and free, and resulting literacy campaigns swept the country, erasing illiteracy rates that had persisted under Batista’s U.S.-backed rule.

For Washington, these reforms were intolerable. The revolution threatened not just American investments, but the very model of exploitation and extortion through which it maintained hemispheric control.

If Cuba could achieve sovereignty, nationalize resources, and improve living standards without U.S. dependence, other nations might follow.

This is the context in which the U.S. embargo was born: as retribution against a small nation that dared to reject economic dependency.

Retaliation Masquerading as Morality: An Empire’s Grudge

This punitive siege, which the U.S. prefers to call an “embargo” is, in practice, an indefinite blockade — an act of collective punishment through sustained economic warfare, specifically to force political surrender.

Officially implemented by President John F. Kennedy on February 7, 1962, it expanded earlier trade restrictions, imposed by an outgoing Eisenhower as Cuba began nationalizing its assets.

Nationalizing its interests challenged decades of U.S. economic dominance — a step that inevitably raised the question of how compensation would be offered.

Despite Washington’s rejection of Havana’s compensation, a reasonable structure was provided. The nascent Cuban government offered bonds tied to the island’s sugar revenues claims over time at international market rates.

The arrangement was consistent with global practice and, given Cuba’s maintenance of a one-to-one exchange rate between its peso and the U.S. dollar, could have been considered reasonable.

Washington’s dismissal, however, fit a familiar pattern. From the Platt Amendment onward, U.S. policymakers had used the language of law to limit Cuban sovereignty while preserving their own power.

By labeling Cuba’s bond plan as “bad faith,” they recycled the same legal pretexts that had long masked exploitation as order.

Havana’s sovereignty was always conditional, subject to U.S. approval cloaked in the language of law; in particular, the language of U.S. law.

The truth? If Eisenhower hadn’t suspended Cuban sugar quotas, operations would’ve continued at previous levels, and the deal would’ve met the standards of fair compensation.

The embargo itself foreclosed that outcome, ensuring failure by design — arguably the only real bad faith in the entire negotiation.

Humidor of Hypocrisy

In what may be the most on-brand moment of Cold War hypocrisy, President John F. Kennedy made sure to secure himself a private stash of more than a thousand Cuban cigars.

He personally ordered his press secretary to procure the cigars just hours before banning them for every other American.

Once the boxes were safely in hand, he signed the embargo, declaring it a noble stand against tyranny.

According to generations of American politicians, the embargo is a principled stand for democracy and human rights.

In reality, it’s a message to the entire hemisphere, if not the world: this is what happens when you defy U.S. hegemony.

Internal government memoranda from the early 1960s strip away the moral varnish.

One State Department memo spelled it out with startling bluntness: the goal was to “bring about hunger, desperation, and overthrow of government” in Cuba.

This strategy echoed punitive tactics used in other parts of the world when client states strayed too far for Washington’s comfort.

The Cuban revolution had simply struck too close to home, a mere 90 miles off of Florida’s coast, in what the U.S. had long regarded as its own island playground.

The Cuban government’s gravest offense, in Washington’s eyes, was in its defiance—embracing socialist reforms, aligning with the Soviet Union, and insisting on sovereign control of its own resources.

By nationalizing U.S.-owned sugar mills, oil refineries, and vast tracts of farmland, Havana signaled that foreign ownership no longer dictated the terms of Cuban life.

For American policymakers — still operating from a mindset in which the entire Western Hemisphere was a U.S. fiefdom — this was heresy.

The historical pattern is uncanny. Whenever European authority has receded, Washington has rushed to fill the power vacuum.

In Hawai‘i, the U.S. backed the overthrow of a sovereign monarchy and used the Newlands Resolution of 1898 to annex the islands without a treaty of cession.

This chain of events would culminate in Hawai’i becoming the 50th state in 1959.

That same year, in Cuba, Spanish colonial rule ended only for the Platt Amendment to tether the island’s constitution to American oversight, transforming a war of Cuban liberation into a war of U.S. conquest.

In both cases, liberation was a cruel illusion, and domination the reality.

This pattern of stepping into the shoes of a departing empire reflects an imperial hunger so deeply embedded in the nation’s political DNA, inherited from its Euro-colonial ancestry, that it survives in the modern era.

As political theorist Noam Chomsky argues, U.S. expansionism should not be viewed as aberrations but as further phases of European imperialism — extensions of the same logic that animated the Doctrine of Discovery.

In this framing, America’s conduct in Cuba was neither anomaly no by accident, but rather a continuation of the centuries-long project of conquest and subjugation.

With regard to Cuba, Chomsky has long maintained that the embargo’s true purpose was to make an example of Cuba — a warning to other nations considering a break from Washington’s economic order.

Its longevity, spanning more than 60 years and outlasting the Cold War itself, suggests that this punitive impulse matters more to U.S. policymakers than any genuine concern for human rights.

If concern for the latter were sincere, the same moral outrage would be applied to authoritarian allies like Saudi Arabia (which executed hundreds last year, often for nonviolent charges) or Egypt (still receiving over $1.3 billion in U.S. military aid despite ongoing political detentions and enforced disappearances).

This is to say nothing of Israel, long bankrolled by U.S. taxpayers (directly and indirectly) and using American weapons to wage a genocidal campaign in Gaza.

Resilience and Innovation: Building Amid Blockade

Six decades of deprivation tell one side of Cuba’s story. Yet what makes that story remarkable is more than the cruelty of Washington’s blockade—it’s the creativity and solidarity it has inspired on the island.

Through an indomitable spirit of community and ingenuity in the face of deprivation, the message is clear: Cuba has not been reduced to dependency or despair.

Instead, it has built parallel systems of innovation that stand in stark contrast to the waste and inequality of its northern neighbor.

Havana’s streets offer a striking example: fleets of 1950s-era American cars, ingeniously maintained for generations, continue to run well into the 21st century.

In the United States, such vehicles would have been discarded decades ago, casualties of a disposable culture that has resulted from an economy that prioritizes consumer led growth.

In Cuba, they are still vital parts of the economy, kept alive by the skill, patience, and inventiveness of resourceful mechanics who rebuild entire engines from scraps.

The same ethic of resourcefulness extends into food and medicine. While the U.S. throws away more than a third of its annual food supply, Cuba has developed localized urban farming networks and cooperative distribution systems that maximize scarce resources and minimize waste.

In medicine, Cuban scientists built a globally respected biotechnology sector, developing cancer treatments and even homegrown COVID-19 vaccines under blockade.

Meanwhile, Cuban doctors, long trained in a system emphasizing preventative care, continue to serve in dozens of countries, delivering aid that positions the island as a humanitarian actor despite its own constraints.

Medical care at home underscores the contrast with the United States. Working with limited supplies under embargo, Cuba built one of the most effective public health systems in the hemisphere.

Life expectancy and infant mortality rates often outperform U.S. outcomes, achievements that reveal both the cruelty of a blockade designed to deny medicine and the shortcomings of America’s own costly, profit-driven healthcare system.

This spirit of solidarity, born of necessity, continues to shape Cuba’s identity.

Neighbors share resources, families stretch meals, and communities organize for survival in ways that embody the same camaraderie and resolve that once toppled Batista’s dictatorship.

Cuba’s story, then, is much more than a tale of victimization by American hostility.

It is also one of a people whose autonomy, ingenuity, and shared struggle allowed them to endure—and even thrive—where the most powerful empire on earth intended them to fail.

Global Rejection, U.S. Stubbornness

Every year at the United Nations, the numbers tell the same story: nearly the entire world votes to condemn Washington’s embargo, while the United States—joined by Israel and occasionally one or two Pacific microstates—stands awkwardly alone.

What was once defended as Cold War strategy has become an annual ritual of humiliation, a reminder that the U.S. is increasingly isolated by the very policy designed to isolate Cuba.

This isolation has grown sharper in an era when fewer nations are willing to humor the petulant adolescent delusions of a superpower clinging to outdated grudges, even as it simultaneously struggles to maintain its stranglehold on global finance, trade, and information flows.

Even close NATO allies and long-standing trade partners in Asia and Latin America view the policy as counterproductive, hypocritical, and corrosive to U.S. credibility.

This diplomatic cost is not abstract. In multilateral forums, from climate negotiations to human rights discussions, the embargo serves as an easy counterpoint whenever the United States lectures others on international norms.

Economically, the embargo isolates not only Cuba but also American businesses from a nearby market of 11 million people.

The U.S. International Trade Commission has estimated that lifting it could boost American exports by over a billion dollars annually, particularly benefiting agriculture, manufacturing, and tourism.

Instead, Chinese, Canadian and other foreign companies fill the void, securing trade deals, infrastructure projects, and cultural exchange that could just as easily flow from 90 miles north.

Put simply, these countries’ markets are filling market roles from which U.S.businesses are barred under the embargo.

The embargo has thus become a case study in self-imposed economic amputation—punishing the target while also inflicting unnecessary harm on the sender.

Meanwhile, in much of the Global South, Cuba remains a symbol of resistance to U.S. intimidation.

The island’s medical brigades, literacy programs, and disaster relief missions have built goodwill in dozens of countries, even as the U.S. has tried to isolate it.

In this way, the embargo has not merely failed to achieve its goals; it has actively undermined broader U.S. strategic interests.

What endures is not Cuba’s alleged threat to democracy, but the myths and hypocrisies that America recycles to justify a cruelty the world has already rejected.

Domestic Political Machinery

Any serious examination of the embargo’s longevity must consider the outsized role of domestic politics—specifically, the electoral gravity of Florida.

The state’s Cuban American community, particularly first wave exiles who fled after the revolution, formed a reliable voting bloc in the U.S. for hardline anti-Castro policies.

In the early years, these exiles wielded perceived moral authority and compelling tales of loss, which politicians leveraged to craft an uncompromising stance toward Havana, and garner public support for the crippling sanctions.

The scheme was simple: promise to keep the embargo intact, and you could count on unwavering support from a passionate, well-organized constituency.

Over time, this anti-Castro lobby made it policy by way of generous campaign donations, disciplined voter turnout, and well-timed pressure campaigns in Washington.

The potency of this machinery lies not in its size—Cuban Americans represent a small fraction of the national electorate—but in its concentration within a pivotal swing state.

No other foreign policy issue is so disproportionately dictated by such a localized interest group, with the exception, perhaps, of the Zionist, pro-Israel lobby.

Even presidents inclined toward normalization with Cuba have been forced to tread carefully; Obama’s partial thaw was carefully workshopped—calibrated meticulously in order not to trigger outright political revolt in South Florida.

However, some view his attempt at reconciliation as the reason Hilary Clinton failed to garner Florida’s 29 electoral votes in 2016.

Yet, as generational shifts reshape Cuban American identity, cracks in the hardline consensus have begun to show.

Younger Cuban Americans, further removed from the trauma of exile and more connected to their island relatives through travel and social media, are increasingly skeptical of the embargo.

Polls have shown majorities supporting expanded travel, trade, and diplomatic relations.

For them, the embargo is less a bulwark against tyranny and more an outdated relic that punishes ordinary Cubans while failing to deliver on its promises.

Still, the political calculus remains stubborn. In tight elections, candidates are reluctant to risk alienating older, more conservative voters who continue to view engagement as betrayal.

The result is a policy frozen not just by Cold War inertia, but by the short-term thinking of electoral math.

This has allowed a regional political dynamic to dictate national foreign policy for more than half a century—often at odds with a broader American public, which, to reiterate, polls show increasingly favors normalization.

Breaking the Cycle of Punishment

Six decades after the United States first imposed its embargo, the policy has hardened into something more symbolic than strategic—less a matter of diplomacy than an unyielding reflex.

The embargo endures not because it works, but because it satisfies a domestic political impulse to punish defiance.

Its moral bankruptcy is plain. Generations of Cubans have been denied access to basic goods, lifesaving medical equipment, and economic opportunity, all in service of a strategy that has demonstrably failed to bring about the fealty it hoped to coerce.

Rather than weakening the Cuban government, the embargo has often strengthened its grip, providing a convenient external enemy to rally against and a ready-made explanation for internal hardships.

For the Cuban people, the result is a daily struggle shaped as much by Washington’s obstinacy as by Havana’s own policies.

Maintaining this course has cost the United States more than it has cost Cuba in certain respects. It has alienated allies, undermined credibility on human rights, and forfeited economic opportunities to competitors.

The near-unanimous global condemnation of the embargo each year at the United Nations is not a diplomatic footnote; it is a standing rebuke that erodes American moral authority in every other arena of international engagement.

Ending the embargo would not erase the past, nor would it instantly transform Cuba into a thriving, pluralistic democracy.

It would, however, acknowledge reality: that engagement, respect for sovereignty, and open exchange offer better paths to mutual benefit than the calcified politics of siege.

The United States could begin to rebuild trust in the hemisphere, expand economic opportunity at home and abroad, and finally align its actions with the democratic ideals it so often invokes.

Cuba’s capacity to endure six decades of economic siege has always rested on its ability to pool resources and prioritize the collective good.

Whether in the creation of a universal healthcare system, the pivot to organic agriculture during the Special Period, or the rapid development of vaccines under blockade, the through-line has been a spirit of camaraderie that treats resilience as a shared project.

This approach has allowed Cubans to thrive in areas where wealthier nations, flush with resources, still fail — especially in healthcare, where the United States continues to treat public well-being as a commodity rather than a right.

It is a lesson worth absorbing. As creeping authoritarianism and the erosion of social safety nets begin to touch even those who once imagined themselves insulated, it becomes harder to deny that survival in an age of instability will depend on working together.

The stubborn belief that one’s money should never be “used to help others” is more than selfishness — it is a structural weakness that ensures collective collapse.

Nobody is an island, and in the storms ahead, those who hoard rather than contribute will find that isolation offers no shelter.

The societies that will endure are those that understand, as Cuba has been forced to understand, that the health and security of the whole directly safeguard the individual.

Reimagining U.S.–Cuba policy is not about absolving the Cuban government of its own shortcomings. It is about rejecting the premise that deliberately impoverishing a nation is an acceptable instrument of foreign policy.

It is about understanding that a great power’s true measure lies not in how long it can hold a grudge, but in how quickly it can recognize the harm that grudge inflicts—and summon the will to let it go.

The embargo’s defenders will call this naïve, an undeserved concession. In truth, it is an overdue course correction. The courage to change course is not weakness; it is strength.

It is the mark of a nation capable of growth, capable of leadership, and capable—finally—of putting humanity above the hollow satisfaction of punishment.